Still playful after all these years, catching up with The Unbelievable Truth last week was something of a difficulty, certainly more so than catching up with its director, Hal Hartley. While I didn’t have to trek all the way up to the SUNY Purchase library (where both he and I attended film school) to have a look at the VHS in one of the smelly, white walled screening rooms in which I and surely many generations of Purchase film students have watched it, some minor detective work was needed to track down a copy of Hartley’s at turns funny and beguiling feature debut, a delightfully po-mo romp that introduced us to a voice that in many ways defined the spirit of American Independent Cinema in the early nineties.

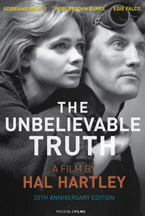

Hartley’s Trust (1990), Simple Men (1992) and Amateur (1994), set in the suburbs of Long Island but seen through Hartley’s rogue and philosophical sensibility, are examples of a type of American cinema that has become both commonplace and all too rare. These days we get vague shadows of films with this kind of buoyancy and sly political satire, films we’re satisfied by calling quirky. Hal Hartley has continued to make films, his style growing more refined and inclusive, yet still singular and challenging. Perhaps more than any recent American narrative filmmaker, he has over the course of an impressive body of work incorporated the cinema of ideas that we find in Godard and Vera Chytilova. Yet his films are always good yarns, ones which engage both the emotions and the intellect; they’ve proven more accessible than most critics give him credit for. Fortunately for all of us, The Unbelievable Truth will no longer be hard to find; a 20th anniversary DVD came out yesterday, one which you can get through Hartley’s website, www.possiblefilms.com. In the meantime, here’s a conversation we had in a Park Slope cafe after a day we both spent editing movies while a little under the weather.

Hammer to Nail: Seeing as this interview’s a look back, 20 years after making the film, my first question is what was your expectation for a career in the film industry then?

Hammer to Nail: Seeing as this interview’s a look back, 20 years after making the film, my first question is what was your expectation for a career in the film industry then?

Hal Hartley: When I was making it?

H2N: When you were making it—or perhaps when you were even conceiving of it in pre-production—and how did that change both in the immediate aftermath of the film’s success (being bought at Toronto), and then years later looking back on it, what were the illusions you had with that immediate success that might have changed?

HH: I think when the opportunity came, that I could make a 35mm feature film for $60,000, I thought to myself, “Well, we probably stand as good a chance as anyone at the moment.” The big hope was just getting it distributed. Personally, I focused on the success of Jim Jarmusch’s first film, and his second film had already come out by then. And I said, “Well, this gives me hope.” I mean, I make a different kind of film, but his idiosyncratic, small film did very good business. So, I was hoping for that. We were hoping for that and that’s what we focused on. We made the film but it sat around for a year. We showed it to everyone, every single distributor in the United States. And everybody passed. I thought something would happen with it eventually but I didn’t know enough. And then the Toronto Film Festival accepted it. It was an audience favorite, I think, that year, and that’s when Miramax came, and Sony Pictures Classics, and United Artists. A lot of people came and started to bid for it. I didn’t know anything about that stuff. We learned really, really fast. Me and my co-producer Bruce Weiss, we stayed in Toronto for a week longer than we were supposed to, just sleeping on couches and stuff, and just learning every day. You know, these distributors would say things, terms, “licenses,” “Do you have an M&E track?” I had no idea what an M&E track was. But we learned. It wasn’t complicated. It was just information that you wouldn’t know simply from having studied film or having made a film. International sales? I don’t think I had even thought of that! [laughs] And that’s significant, for the second half of your question, because years later I see that my career really happened overseas. More people saw my first two or three films overseas more than they saw them here. My career has really been built on that.

H2N: Has it been a difficult thing to come to terms with that? That you feel like the primary audiences who you’re making films for are not necessarily the type of people you tend to make films about?

HH: No. It was different back then. The earlier films I made for the kinds of people they were about. Youth. You know, I felt young and I was trying to make films about being young in this culture, and I felt like, “Yeah, this will probably speak to other young people who feel a little bit alienated or have a different kind of engagement with their culture.” However, I remember James Schamus writing an article that it was really the middle-aged people who were responding to my early films. He spent a lot more time thinking about distribution trends, and he wrote that in an article about this topic specifically. So, I don’t know. These days, it’s much different, I feel like. It’s not the same thing. I’m not trying to hit a very specific audience, a demographic of young people or middle-aged people. But back then, the early films, yeah, I wanted to make films about the experience I was having as a young person in the world that I really felt strongly other people my age would respond to. And I might have been wrong about that, if James is right.

Hal Hartley

H2N: Have your filmmaking preoccupations changed or shifted over time, and how does that color how you look at those early films now as a viewer? Do you ever watch them?

HH: Well, I had to watch this one a lot recently, The Unbelievable Truth. Yeah, it is different. Simply just growing older, you make films about different subject matter. And you also get more practiced and experienced. You get more sophisticated with what you want to try. I mean, I look back at The Unbelievable Truth now and it’s very simple. Part of its charm, I think, is in its simplicity. I think there are some really dumb jokes that I would never allow in my newer work. But they’re so joyous in a way, the joy of making people laugh just by some stupid sight gag. That was the level of filmmaking I was on. I knew I was probably doing something different with dialogue, because I had been making short films before that and everybody—even Ted [Hope] actually, I became friends with him in the couple years before The Unbelievable Truth, he had seen my short films to0 and he said what everybody said, “You’re doing something different with the language.” And I couldn’t really put a name on it, except I was trying to… I just liked rhythm. And when the film came out and got some nice reviews, or even bad reviews, people talked about that, about the rhythm. They were always talking about the dialogue, which I felt relieved about because there were some other aspects of the filmmaking I thought were very amateur and just done without the proper resources.

H2N: Looking back on it, it seems to me like something you’re doing that I find really invigorating still, is that there was a certain sort of doctrine of American Indie Realism, a “regional naturalistic cinema,” that people thought of when they thought of independent film in 1988 or ’89.

HH: Yeah, these things that were associated with PBS and the Sundance Institute films and stuff.

H2N: Sure. And I think that there’s a certain, one could say charm, one could say a heady post-modern flair, to some of the dialogue, and the concerns that the characters have within your film, married to a distinctive grammar, which still really appreciates longish takes and whatnot. That was really unusual then and it’s still pretty unusual now. But I do find it interesting that there’s been this whole genre arrive in independent film of the sort of quirky comedy of alienation that I think in a lot of ways you pioneered. Do you see that influence in contemporary filmmaking?

HH: Where the influence comes from might be an explanation. For me, I don’t find it very unusual in history, going back three or four hundred years of plays and novels, comedies about people who are less than comfortably integrated into their social milieu. So, Moliere was a huge influence on me. Without having really experienced much of that as theater, really just reading the plays. Yeah, social satire. That’s where that came from. The particular way I made that film, though, at the time you just, you’re there, you’ve got some money, you have to make a film quickly, you’re affected by what came immediately around you too, and Jarmusch definitely was into that, again, you described it very well. He’s doing a very particular type of thing too, but they are these long takes, and they’re—in a certain sense—naturalistic, but they’re highly thought, they’re highly written, they’re very carefully crafted.

H2N: The stylized version of…

HH: Of time passing, which I still think he does better than anyone. So that was quite an influence. I was very, very excited about Jim’s films. Even recognizing that when I was watching them, if I had to make a film right now I wouldn’t make a film this way. But I was very excited about them, that the characters could be a little open-ended too, they didn’t have to be as clearly defined as a more conventional drama or comedy wants them to be.

H2N: How were you seeing those films in this era, in the mid-‘80s. Obviously there were rep houses and the Jarmusch films were getting distributed, but was there a strong social scene that revolved around those films and filmmakers that you were a part of or wanted to be a part of?

HH: I don’t remember that. I think certainly most people I hung out with were either filmmakers or actors or, you know, we had painter friends and stuff like that too. We were always talking about film and we were always going to the Film Forum. That was really the base, the Film Forum, and Anthology Film Archives. I think Jarmusch’s first film came around, it was like, wow, this is something you could almost see at the Anthology Film Archives or Millennium or the Film Forum. Or at a Loews cinema. That hadn’t happened in those couple years I had been living in New York and watching films all the time. Alan Rudolph was another big influence to me at that time. The Moderns, Choose Me, Trouble in Mind. So there were contemporary filmmakers that I was inspired by.

H2N: At what point did you decide that The Unbelievable Truth would be the project you would first tackle.

HH: It came when the money…

H2N: Was it 75 grand?

HH: It was 60, and then we got another 15, so it was 75 altogether. It was 75 with all the deferrals, so it was really 60. I had been working on a couple of different scripts, and I actually was trying to make a 16mm one-hour version of what eventually became Simple Men years later. Then, this situation came up where I got this money to make a 35mm film, got the equipment and everything, and so I just spent about three weeks writing The Unbelievable Truth. I had different ideas that were all unfinished, and they all had to do with money, a reevaluation of the dollar. And something about the history of our nation, the founding fathers. That’s where the George Washington stuff comes from. Anyway, there was one story that had to do with this guy in my hometown who’s got problems of his own but he keeps meeting the ghosts of the founding fathers around town, like at the McDonald’s he meets Benjamin Franklin. And he has these conversations with the founding fathers. I took ideas from that. I had this other kind of Romeo and Juliet story. To say I hammered it together sounds like I wasn’t really caring about it, but the impetus was the money. Suddenly, the opportunity was there and I took it. That’s the straightest story of all these that I have.

H2N: Thinking that you had to do something that was relatively accessible?

HH: Not just had to. I wanted to. I thought I was making the most accessible film in the world. I always do.

H2N: The environment in which you were trained and in which I was trained, kind of willfully wanting to make esoteric work, maybe more so than some of the other prominent film schools…

HH: Yeah, because they fostered less of a professional training school type of thing. I think a year before I made The Unbelievable Truth, I had probably—and I had been out of school for almost four years—I think I had probably gotten down with the prospect of living a life making very obscure—but not esoteric—just obscure art films. Narratives, but not conventional in their structure and length and all that. And something happened in my writing that year, late 1987/1988. First of all, I did an enormous amount of writing, lots of projects, lots of scripts written. I think I finally got my teeth into telling a story. I felt more confident about it than I had before. And the short films I had made were probably the way out of it. I think they’ve grown from obscure to less obscure to least obscure to The Unbelievable Truth. Like I said, I thought I was making an episode of I Love Lucy. I thought it was that accessible. It was successful but, you know what I mean, it’s not Judd Apatow.

H2N: So did you meet Robert [John Burke] in Purchase, at school?

HH: I did. We started and graduated at the same time. And he was going to be the lead actor in my senior thesis film at Purchase, but for various reasons he wasn’t allowed to. But we knew each other quite well.

H2N: And Edie Falco as well?

HH: I didn’t know her at Purchase. I met her after Purchase. We were just in the same crowd of people. She was like two years after me, I think. Yeah, we were hanging around Brooklyn, we were all making little films. She was a natural.

H2N: What did you learn about working with them and working in this distinctive style and mode of performance that you fostered on this film? Was it difficult for them?

HH: No, it was very easy. Everybody took to it right away. I remember the first reading with everybody around the table at the same time, and it was really hilarious. People were just laughing. So it came very easy. And everybody recognized, without having to talk about it, that it resided in the dialogue. So just trust the dialogue. Know the lines, say the lines, do what Hal asks you to do in terms of physicality, which is pretty simple. You know, we couldn’t do much elaborate stuff in that film so we just trusted the dialogue. If they understand the line, what it means, then they understand how to be, what to do. I mean, it was a lot simpler than, say, Trust. With Trust, there was a lot more discussion moment-to-moment about what things meant. That was a number of more degrees involved.

H2N: Are there aspects of the innocence you had brought to a first, second, or even third feature that you miss ever?

HH: Not really. When I watch The Unbelievable Truth now I cringe a lot. I should not have been that innocent by that point. No, and in any event it’s impossible. You can’t return to innocence. So it’s a bittersweet thing. But there were some nice, easygoing gags. I remember, when I watched that just recently, when Mark Bailey hits his wrench into his toolkit and it falls off the edge of the car, I said, “That’s so well done!” It’s the simplest thing, it’s the oldest gag in the book, I mean, that’s the first thing silent films discovered probably: mistakes, accidents. It was very satisfying to see people laugh. I always try to remember that. Even if I’m cutting now, or things in Fay Grim, something like that where it’s still very much about dialogue, but there’s a way in which you can think about the editing, eye contact, moving away, pulling pauses into things… they’re a lot like slapstick as well. And at a certain point, after a certain amount of investigation it’s always great to just take a breath, look at it, and what’s the simplest way to do what you just did there? That’s the final revision of that moment and it works well. That process still works for me.

H2N: You’re not making movies for $60,000 anymore.

HH: Yes. No more.

H2N: And yet, it seems like financing independent films is more difficult than ever. I read somewhere where you claimed that you actually had no intentions of making movies in the States anymore? A few years back?

HH: No, I don’t think I said that, but it did look that way. I mean, I moved away. I lived in Germany for five years, because I had work there. I didn’t know if I was going to come back. Parker likes to say that—Parker Posey—“You can’t even make films in America anymore!” At the time we were making Fay Grim she thought there was a whole conspiracy about it. I’d say, “It’s not just me. Everybody has a hard time.” But it’s like it usually is. It’s technical and economic. Films have become quite inexpensive to make if you’re not trying to make things that huge corporations can make easily. Hollywood does Hollywood better than anyone else; you can’t fake that. If I want to see a James Cameron movie I want to see James Cameron do it. What I did with The Unbelievable Truth in 1988 you could really do for $20,000 now.

H2N: That’s what the feature I just shot cost.

HH: Yeah. I think that’s good. The other complicated part, which other people have to figure out is how do you make money, how do you make a living being a filmmaker? Or how do distributors and sales agents, how do you sustain an industry where there’s so much product? Somebody’ll figure it out. I don’t know.

H2N: But I believe that you own the rights to a number of your films, you market them yourself through your website.

HH: I don’t own them completely. I control the rights. I own it with another individual, a group of individuals, but I’m in charge of marketing and all that. It’s funny, I had a conversation with Atom Egoyan a couple of years ago in Toronto. We found ourselves just like two older men sitting on this couch saying like, “Why did we do that? Why did we think it was a great idea to own all the rights to our films?” Because it’s so much work, and you almost always have to have a staff. There have been benefits and I’m happy, but it is a lot of work. It costs a lot of money to maintain an infrastructure that can look after the rights. But sometimes, like with Fay Grim, I don’t own anything about that, I just got paid for one of the first times in my life, I got paid as a writer and director. I did okay. I thought the money was great. But if I had controlled it, it would have been distributed better. I would have had more say in how it got distributed and sold overseas. But sometimes you have to just shut up. You get the money and just shut up. Particularly in that case, where they didn’t have too many needs as regards to the film. They didn’t have notes. They wanted a Hal Hartley film by Hal Hartley, so that was a nice situation. So you compromise.

H2N: Have you ever been lured to go make studio work or work that was more industrial?

HH: Yeah. In the beginning of my career, perfectly nice people from movie studios would take me out to lunch all the time and ask me if I wanted to direct scripts they sent me, after The Unbelievable Truth. Even a little after Trust. They thought I might be a good guy for comedies like… I don’t know who made them, but things like Dude, Where’s My Car? I got a lot of that kind of stuff after The Unbelievable Truth.

H2N: A Purchase graduate directed that.

HH: Danny [Leiner], who’s a friend of mine. So, I read the scripts and I wasn’t interested at all but these were perfectly sensible, nice people. That’s their job, to go out and find new talent for the product they’re manufacturing. I think after Trust I began to recognize that I really meant it, that what I was doing wasn’t a poor man’s version of what they were doing. I was doing something I really believed in. It is what it is, which is different too. It’s socially critical and involves, as you mentioned before, modernism. So it reflects on its own making. Anyway, not so easy to market as the things that they would like to market. So, then, I got less and less of that. These days, I’d be very curious. I’d love to actually do a job for hire. I made a TV commercial once that I was just excited to be… I have a lot of craft too.

H2N: Do you see that as an “ideals of your youth” thing…

HH: That I wanted to make the kind of films I wanted to make the way I wanted to make them?

H2N: Absolutely.

HH: No, I still do that. That’s a life idea. But still, you don’t have to pursue that 100% all the time. If you’re successful, you’re making a lot of money and your company is functioning okay, it’s really great. But, you know, you don’t make so much money doing this. At the same time, you have all this craft and experience. If somebody needed a commercial I’d say, “I’m your man. Just tell me what you want and I’ll manufacture it for you, I’ll do it.” It was really funny, they were like, “Oh, we really want a Hal Hartley image, we really want a Hal Hartley attitude.” I’m like, “Dude, I don’t really know what that is, but if you tell me what you’re expecting, I could probably work backwards and kind of retro-fit the image to what you need.” [both laugh] It was a great experience actually, but it was a little frustrating to get past the talk.

I’ve also spent a lot of time teaching and a lot of time doing workshops and stuff where I’m really a mechanic who comes in and works with people on the script. You know, “This will work there; have you thought about taking this part out?” And I enjoy that kind of craft. When I’m teaching or running a workshop I don’t think about it any other way. I’m an experienced craftsman who could probably be of use to these usually younger people who are making their first film. That’s a nice day’s work, at the end of the day.

— Brandon Harris