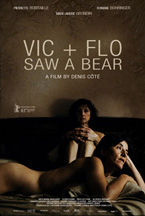

A Conversation With Denis Côté (VIC + FLO SAW A BEAR)

(Vic + Flo Saw A Bear opens theatrically at Anthology Film Archives on Friday, February 7th, 2014. Visit the KimStim website to learn more.)

(Vic + Flo Saw A Bear opens theatrically at Anthology Film Archives on Friday, February 7th, 2014. Visit the KimStim website to learn more.)

It may be only February, but I’d put good money on the possibility that, come December, I’ll still be chewing on the latest feature by Canadian filmmaker Denis Côté, Vic + Flo Saw a Bear. I recently got the opportunity to meet with Côté in downtown Manhattan, and we talked film form, the differences between fiction and documentary, and what exactly he was going for with the startling and challenging Vic + Flo. ***Be advised: there are some spoilers in the conversation that follows.

H2N: What, if anything, compelled you to make an overtly fictional film like Vic + Flo Saw a Bear following Bestiaire [2012], which most considered to be a documentary?

Denis Côté: I wouldn’t say “following Bestiaire,” I would say “following Curling [2010].” As you know, I manage to make a film a year, so I make “big films” and “small films.” Those are not good words, but… Something like Curling is a two-year project, and you get money from commissions which supports you in making a $1 or 2 million film, so you really have to script something. When I finish working on one of those films—productions with 25 people—I want to take my revenge, so I always make these kinds of D.I.Y. films like Bestiaire, Carcasses [2009], and the new one I just did after finishing Vic + Flo. I call those my “revenge against the industry” films. Only three people, no money, only camera and sound, and we improvise something. There’s certainly no script. My last “big” film was Curling, so I was ready to do something with a big crew and actors. But with Vic + Flo, I was also wondering, “what went wrong with Curling?” I found the same kinds of themes from Curling in Vic + Flo—like that of living outside of society—and I thought about people coming out of jail, how they have no connection to society and have to rebuild everything. This is my eighth feature film, so I don’t have the same sense of urgency that I used to have. It’s just a new film, then a new film… There was nothing I strongly needed to address, I was just revisiting my usual themes, and I wanted to write for female characters. In the end, I have no clue what that film is. Is it funny? Is it dark? Is it a horror film? Is it a vengeance film? The competition at Berlin was very interesting for me. The film won something, and now it has this whole one-year life. But I didn’t know what I had on my hands until it was over.

H2N: Based on what you just said about your production methods, do you think that there’s a meaningful difference between fiction and documentary, and how did that inform your approach to making Vic + Flo?

DC: I used to think a lot more about the clashes between fiction and documentary. At the turn of the 2000s, we had all these films by Jia Zhangke and Tsai Ming-Liang, and I was really interested in what they were doing. And then came this “cinema of the in-between” [H2N note: the so-called “docufiction”]—my first film, Drifting States [2005], is all about that. I don’t think I’m past that, and I can still try some stuff, but I don’t think about it too much now. I just finished a film about the idea of work, so we filmed workers for 70 minutes, and then brought some actors in. The resulting effect was just there, it wasn’t the product of a thought process. You stop thinking so much about the “recipe” for your film. But I used to think about the “recipe” a lot.

DC: I used to think a lot more about the clashes between fiction and documentary. At the turn of the 2000s, we had all these films by Jia Zhangke and Tsai Ming-Liang, and I was really interested in what they were doing. And then came this “cinema of the in-between” [H2N note: the so-called “docufiction”]—my first film, Drifting States [2005], is all about that. I don’t think I’m past that, and I can still try some stuff, but I don’t think about it too much now. I just finished a film about the idea of work, so we filmed workers for 70 minutes, and then brought some actors in. The resulting effect was just there, it wasn’t the product of a thought process. You stop thinking so much about the “recipe” for your film. But I used to think about the “recipe” a lot.

H2N: How do you think your background as a film critic influences your filmmaking?

DC: Although I say I’m not so cerebral anymore, I’m still totally obsessed by form. I have to agree with people who say that my approach to storytelling is “cold.” I’m not a good storyteller, and I don’t like cinema for its entertainment value. I don’t need to be entertained when I go to see a film. For me, entertainment is everything outside: reality is entertainment. That’s why my films are a bit dry and cold and everything seems to have been cut together with a machete. I’m sorry to say there’s not enough heart in what I’m doing—but there are so many filmmakers out there doing everything with their hearts, so why should I? For Vic + Flo, I was primarily thinking, “Can I tell a story going this way—an intimate love story—and then bang, go this other way and make a vengeance film? Am I even allowed to do that? And why should I try?” I love the fact that I can’t please everyone, because it means I’ve tried something. Film language will always be more important for me than entertainment.

H2N: There’s certainly a tenderness to much of the film, but when you introduce the element of violence, it seems to originate from a more conceptual place than with other filmmakers who try to think about violence through cinema.

DC: They would film violence as a fetish. In Vic + Flo you can tell that I’m not that interested in violence, that it doesn’t totally arouse me. For me, the ending was a way to find a romantic conclusion for these two women. Like, how can they finally be together forever? They go through a difficult process, and then there’s this “beautiful” kitsch ending—the resurrection crap and everything—but they have to go through something.

DC: They would film violence as a fetish. In Vic + Flo you can tell that I’m not that interested in violence, that it doesn’t totally arouse me. For me, the ending was a way to find a romantic conclusion for these two women. Like, how can they finally be together forever? They go through a difficult process, and then there’s this “beautiful” kitsch ending—the resurrection crap and everything—but they have to go through something.

H2N: It feels a little less blunt than something like the ending of [Catherine Breillat’s 2001 film] Fat Girl, where the violence similarly comes from out of left-field.

DC: I really don’t like that film, but I see what you mean. After Berlin, I was reading some reviews, and the worst review I read was like, “This film is trying everything to be original.” I don’t want to read that. That was the goal and the danger of the film—casting-wise, storytelling-wise… I’m about trying things more than about succeeding or making my masterpiece. When you make a film a year, of course you go too fast. I know that. I made Bestiaire in eight days, I just made a new film in seven days, I made Vic + Flo for $2 million in 25 days… just listen to me, I talk fast… I just want to try things.

H2N: You mentioned casting, I was wondering about the casting process and how you settled on those particular actors?

DC: Well, it’s hard when I talk to Quebecois people about this, because Pierrette Robitaille [the actress who plays Vic] is famous in Quebec for playing in very silly comedies, TV movies, theater… She’s famous for being—this is not a good word, but—a clown. And when people read that I was working with her, they freaked out. I think a lot of people wanted to see how the hell you can put her and me together in a film. She had never played a role like that. Usually, she’s externalizing everything all the time, but in this, she’s internalizing. Casting her was a gamble. Every day she would say to me, “Why? Why? Why?” I didn’t tell her, “You’re the best actress I know,” I told her, “You’re a challenge. I want to see what I can do with an actress like you.” Romane Bohringer [the actress who plays Flo]… I wrote in a part for a French actress, and it was supposed to be another actress and Romane replaced her three months in advance. She’s my age and comes from art cinema, so with her, it was perfect. And Marc-André [Grondin] is more like a French/Quebecois star… But I know that having these three people together doesn’t make sense. Again, that’s the challenge I wanted.

DC: Well, it’s hard when I talk to Quebecois people about this, because Pierrette Robitaille [the actress who plays Vic] is famous in Quebec for playing in very silly comedies, TV movies, theater… She’s famous for being—this is not a good word, but—a clown. And when people read that I was working with her, they freaked out. I think a lot of people wanted to see how the hell you can put her and me together in a film. She had never played a role like that. Usually, she’s externalizing everything all the time, but in this, she’s internalizing. Casting her was a gamble. Every day she would say to me, “Why? Why? Why?” I didn’t tell her, “You’re the best actress I know,” I told her, “You’re a challenge. I want to see what I can do with an actress like you.” Romane Bohringer [the actress who plays Flo]… I wrote in a part for a French actress, and it was supposed to be another actress and Romane replaced her three months in advance. She’s my age and comes from art cinema, so with her, it was perfect. And Marc-André [Grondin] is more like a French/Quebecois star… But I know that having these three people together doesn’t make sense. Again, that’s the challenge I wanted.

H2N: There’s a continuity in terms of the performance styles across all of your fiction films, the one exception maybe being Drifting States.

DC: With the non-professionals everywhere…

H2N: Right. So I was wondering, when you’re directing your actors, do you actively think about coaxing that kind of mannerism from them or do you do it more intuitively?

DC: In the past I didn’t want the actors to be robotic, but I wanted psychology to be somewhere else, on another planet. That was the case with All That She Wants [2008]. I’m not a big fan of the film now. I think it was a transitional film, and it’s not me. With Curling, I found something more naturalistic, but with so many silences and pauses, and it almost seems a bit static. The same goes for Vic + Flo: I think they play in a very naturalistic way. But do you feel it’s static?

DC: In the past I didn’t want the actors to be robotic, but I wanted psychology to be somewhere else, on another planet. That was the case with All That She Wants [2008]. I’m not a big fan of the film now. I think it was a transitional film, and it’s not me. With Curling, I found something more naturalistic, but with so many silences and pauses, and it almost seems a bit static. The same goes for Vic + Flo: I think they play in a very naturalistic way. But do you feel it’s static?

H2N: No, I don’t, but there are some characters that are very—

DC: I think I got some humor out of them… I’m just sure that this film doesn’t take itself too seriously. But I also didn’t want to make it a freak show. People have been bringing up the Coen brothers—because they also film people in the woods?—but I see what you mean. Curling was a bit less deconstructed. In Vic + Flo, I still think they play in a naturalistic way—according to my definition of “natural,” however…

H2N: As far as the compositional strategies in the film, they seem very similar to those in your previous films, like the very frontal, wide—

DC: Tableaux stuff…

H2N: Yeah. Do you find that that’s kind of a default mode that you return to, or is there some other intellectual or cinephilic basis for it?

DC: My first two films were mostly handheld, and I ended up having a strong rejection of that style at some point. And then in All That She Wants I went too far in the opposite direction. Then I discovered in Carcasses that making a documentary with fixed shots was an amazing challenge for me. And this was strongly manifest in Curling. I love composition. You say “default,” and yes, the new film is very much like that as well… but, I mean, what question about this would you ask Ulrich Seidl or Nikolaus Geyrhalter? When you feel comfortable doing something—even though I said I like to put myself in danger—at some point you find your visual recipe, and the problem becomes repeating yourself. People will get bored with that. But no, I don’t think I’ve done all that I can do with that territory.

DC: My first two films were mostly handheld, and I ended up having a strong rejection of that style at some point. And then in All That She Wants I went too far in the opposite direction. Then I discovered in Carcasses that making a documentary with fixed shots was an amazing challenge for me. And this was strongly manifest in Curling. I love composition. You say “default,” and yes, the new film is very much like that as well… but, I mean, what question about this would you ask Ulrich Seidl or Nikolaus Geyrhalter? When you feel comfortable doing something—even though I said I like to put myself in danger—at some point you find your visual recipe, and the problem becomes repeating yourself. People will get bored with that. But no, I don’t think I’ve done all that I can do with that territory.

— Dan Sullivan