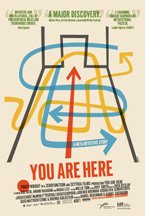

A Conversation With Daniel Cockburn (YOU ARE HERE)

“Peanuts is this world of people in isolationist fantasies,” Canadian video artist/feature filmmaker Daniel Cockburn says over the course of a conversation. He brings up Charlie Brown and Peanuts after seeing the phrase “Charly Brown” in my notebook. It was just the nickname of a person whose number I wrote down the week before, but Cockburn’s meaning-making, and my eagerness to latch on to this meaning-making in a desperate, undergrad-amateur way to better grapple with the work in question—his conceptual, curious, but warm first feature, You Are Here (2010)—seems all too appropriate.

“Peanuts is this world of people in isolationist fantasies,” Canadian video artist/feature filmmaker Daniel Cockburn says over the course of a conversation. He brings up Charlie Brown and Peanuts after seeing the phrase “Charly Brown” in my notebook. It was just the nickname of a person whose number I wrote down the week before, but Cockburn’s meaning-making, and my eagerness to latch on to this meaning-making in a desperate, undergrad-amateur way to better grapple with the work in question—his conceptual, curious, but warm first feature, You Are Here (2010)—seems all too appropriate.

Cockburn’s video work (grouped under his website, titled zerofunction) is both precise and a lot of fun. In Metronome (2002), Cockburn narrates and performs the same repeated beat, while explicating the rhythms of end-of-century, white-collar rebellion chic films like Fight Club (1999) and The Matrix (1999).

You Are Here consists of episodes of humans trying to comprehend their own consciousness and constructs of space, direction, and knowledge production: a crowd collectively known as “Alan” struggles to establish some sort of stable, fixed knowledge, while in another sequence, a man who doesn’t know Chinese reads the language after an instructional book is slipped under a room that’s essentially a model of the mind.

But these conceptual set-pieces have an emotional underpinning. In one of her last performances, the late, talented actor Tracy Wright (Monkey Warfare, Me and You and Everyone We Know) plays an archivist whose materials are resisting her efforts at storage: “Things aren’t staying where I put them, and I’m pretty sure it’s not my fault.” It’s poignant because I know this is one of her last movies, and also because it so perfectly explains the frustration of every impermanent relationship.

Cockburn moved to New York last year, and his first feature, You Are Here, opens on Friday, May 11, 2012, for a one-week run at the reRun Gastropub.

Hammer to Nail: I watched your short videos yesterday [which Cockburn performs in], so they’re fresh in my mind. Was there ever a point when you thought about putting yourself in the film, or using yourself as an entryway into this movie?

Daniel Cockburn: Yeah, I actually intended to play the part of the guy in the Chinese Room. I totally thought that was going to be me, partly because I thought this [role] is sort of similar to videos that I made before where I was the performer. So I thought, well, I could do this. I’m not an actor, but I could give a performance that could work here for the concept. And I also just really liked, structurally, the center of the movie being about someone who puts himself in his own experiment, and I as the moviemaker, putting myself in the role.

Daniel Cockburn: Yeah, I actually intended to play the part of the guy in the Chinese Room. I totally thought that was going to be me, partly because I thought this [role] is sort of similar to videos that I made before where I was the performer. So I thought, well, I could do this. I’m not an actor, but I could give a performance that could work here for the concept. And I also just really liked, structurally, the center of the movie being about someone who puts himself in his own experiment, and I as the moviemaker, putting myself in the role.

But when we were doing auditions I used Chinese room text as audition material as a test, and this one guy, Anand Rajaram, read the Chinese room text in a way that was creepy and hilarious and upsetting at the same time; he’s many things at once, he’s a really unique performer. As soon as I saw him, I thought I’ll fire myself and let him do it. And I’m really glad I did.

H2N: Was it an adjustment for you to direct trained actors?

DC: That was the thing that I think I was worried about more than working with a crew. In the end, for the most part, it was really easy… or easy compared to what I thought it was going to be. I was just worried that we were going to get to the set, and that I’d have to work with the actor to build their character from scratch and answer all of these basic questions, because we had practically zero rehearsal time. There were just going to be fundamental things about the character that I’d need to clarify. And then we started making, it and the first couple of days it was just Tracy alone, in the archive. And I realized after 20 minutes of shooting, well she’s already figured it out, she’s already built the character. If I see something that isn’t what I want, I can try to point her in the right direction, but 95% of the work is already done, it’s just fine tuning. Frankly, they were professionals, and I encountered for the first time the benefits of what it is that professional actors can do.

H2N: How did you approach Tracy Wright?

DC: A colleague of mine who worked in experimental theater connected us, and I send her the script and she and I met. We had coffee and it lasted three and a half hours, and we really enjoyed each other’s company. Everything about the meeting was positive. There was this tinge of her not quite getting the script. I know she liked it. She said, “I liked the script, but I don’t know if I get it.”

DC: A colleague of mine who worked in experimental theater connected us, and I send her the script and she and I met. We had coffee and it lasted three and a half hours, and we really enjoyed each other’s company. Everything about the meeting was positive. There was this tinge of her not quite getting the script. I know she liked it. She said, “I liked the script, but I don’t know if I get it.”

Later in our long coffee meeting, I was just sort of talking about where this script came from for me, and that it was related to a period I’d gone through of intense meaning-making. We’re all making meaning of things all the time… synchronicities and coincidences really seemed to mean things. I’d be looking at any text I’d encounter like a menu or road sign and I’d scramble the letters around and see if there were any different codes there that needed to be deciphered.

It took me a long time to realize that there were emotional underpinnings to this emotionally exhausting behavior. It became something that wasn’t just an enjoyable intellectual play. It became something that was really exhausting and troubling. In a number of ways I worked through it, and part of that was figuring out what the emotional reasons were for this intellectual…

H2N: …Magical Thinking?

DC: …Emotion seemed like a tangential realm, and now I’ve come to think of it almost in the opposite way.

When I described to Tracy this emotional experience that I had—paranoia is the best word to describe it—I think that made her go, “Okay, I think I get where you’re coming for, what to look for in this character.” I could be wrong, but I think I gave her something to build from. And she built something more human and complex and real than what I imagined.

The journey of mine over the years of realizing that my intellectual thought patterns have emotional sources, in a way was mirrored in the process of making the film. I started writing it as a very intellectual pursuit, and through making it and collaborating with other people, like Dan Bekerman the producer, and the director of photography [Cabot McNenly] and the production designer [Naz Goshtasbpour], all these people with all of their ideas, and these actors who gave human reality to these concepts that I had written down, that creative evolution from script to human movie is parallel to the journey of realizing that intellectual traps and thought patterns have an emotional underpinning.

H2N: Explain a “zero function” to me [Zerofunction.com is Cockburn’s website].

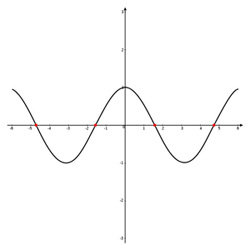

DC: I took math in high school. I liked it. Basically, if you have a function like f(x) = x2+5 . So any number that you put in, you square it, and add 5, and that gives you an answer. It’s like this box where you put in one number and you get another number. And then you draw a graph and so every number you put in on the x-axis gives a number on the y-axis and it makes a shape.

DC: I took math in high school. I liked it. Basically, if you have a function like f(x) = x2+5 . So any number that you put in, you square it, and add 5, and that gives you an answer. It’s like this box where you put in one number and you get another number. And then you draw a graph and so every number you put in on the x-axis gives a number on the y-axis and it makes a shape.

H2N: So output is dependent on input. There’s a utilitarian function to everything.

DC: Exactly. And if you know what the output was, then you could work it backwards and determine what the input was. There’s a very clear relation.

But zero function, as far as I know, is just this stupidly simple thing, where instead of f(x)=x+5, it’s just f(x) = 0. It doesn’t even matter what number you put in for x because this function just says “I don’t know care what number it is, it just = 0”… If you put in anything, you get 0. So it means it’s this black box when you put something in and you get something out. But you can never determine from the output what [was the] input. I remember I learned this in grade 12, thinking that this was really freaky. It just annihilates the past. If you put something in you put something out. Whatever you get is zero, and there is no possible way… it’s like a murder mystery where you know that there is no way you’ll find out who did this.

H2N: What are your Q&A’s like?

DC: Q&A’s are often really good, which is sort of surprising. They’re good when people are really interested in grappling with the material. When people are affected by something, they aren’t just playing with ideas for the sake of playing with ideas; there’s an urgency behind them. It becomes a real conversation, and I hear surprising things.

DC: Q&A’s are often really good, which is sort of surprising. They’re good when people are really interested in grappling with the material. When people are affected by something, they aren’t just playing with ideas for the sake of playing with ideas; there’s an urgency behind them. It becomes a real conversation, and I hear surprising things.

At the Toronto Film Festival, a number of people asked the actors what they thought the movie was about. Most of the actors had just seen it for the first time. And R.D. Reid [who plays the Lecturer, Dr. Eisenberg] said, “I think this film is about the attempt to deal with a deep-rooted despair.” And I was really surprised to hear that. He and I had never really talked about that, or much of anything like it. But I was really gratified to hear him say that. I thought that is a very appropriate interpretation of the movie.

H2N: Do you see it as a despairing movie?

DC: Yeah, mostly. A couple of people have written about it being hopeful, which I’ll accept.

DC: Yeah, mostly. A couple of people have written about it being hopeful, which I’ll accept.

H2N: So it’s like plush despair.

DC: Yeah, or suede.

H2N: If you could show this movie as a double feature, what would you show it with?

DC: I showed the movie at a space in Rotterdam a few months ago, and they gave me carte blanche to program on another night, and I showed Schizopolis [1996, Steven Soderbergh]. It’s just this freewheeling movie… “Say goodbye to most of the rules of narrative except the ones that I want to use and I really know how to use them and make them potent.” I have the feeling that the sentence I just spoke is missing a noun at the very end. Maybe if I put movie at the very end; It’s very funny, and it’s exciting in this off-the-wall kind of way. But I think it’s also really sad and melancholy, and has this almost hopeless insight about human relationships, but it has a not-superficial ray of hope at the end.

— Jason Klorfein