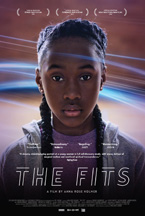

A Conversation With Anna Rose Holmer (THE FITS)

(Distributed by Oscilloscope, The Fits opened in NYC on June 3rd, and opens in LA, Cincinnati, and Pasadena on June 10th before expanding into other cities.)

(Distributed by Oscilloscope, The Fits opened in NYC on June 3rd, and opens in LA, Cincinnati, and Pasadena on June 10th before expanding into other cities.)

Though it’s only her narrative feature debut, Anna Rose Holmer has nonetheless delivered one of 2016’s fiercest and most exhilarating new releases with The Fits. In this mesmerizing work of pure cinema, breakout newcomer Royalty Hightower stars as 11-year-old tomboy Toni, who lives in Cincinnati’s West End neighborhood and trains as a boxer under the tutelage of her older brother, until she becomes fascinated with the glamorous girls’ dance squad that practices nearby. As Toni feels an increasing pressure to choose between her newfound interests, her community is disturbed by a mysterious outbreak of fainting fits and spells that afflict an increasing number of girls. The Fits fires on all cylinders, featuring stunning cinematography, sound design, and performances. On the cusp of its release in New York City, I spoke to Holmer about how she was able to bring this exceptional vision to life.

Hammer to Nail: I’m currently disillusioned with the current state of financing when it comes to getting original and ambitious narrative feature films made. Without getting into budgetary specifics, can you discuss how you paid for this movie? Because while it shouldn’t, the mere fact that The Fits exists feels like some sort of glorious miracle.

Anna Rose Holmer: I had heard about the Venice Biennale program from the first year it existed, and it seemed like such an exciting way to make a film. So even before we formally applied I was thinking about the strengths and style of that program when I was thinking about The Fits. It was our first choice for financing this film and the only way we actually went about it. The Fits was entirely grant supported, our key funder being the Venice Biennale program. In addition to financing, they were mentors and provided development support for the film, and they really championed experimentation through the process. The support wasn’t just project based but the artist behind the project; they made sure that the film was satisfying other artistic needs and was taking risks. Besides just being a finished film, was it furthering my ideas about cinema? Was it challenging to me as a creator? And I think that’s very rare. So that’s why I wanted to develop the project with them. And then the Sundance Institute came on, and Cinereach and Rooftop. With all of those partners, it was always about: how do we amplify the risk and challenges that you’re facing in an exciting and constructive way and not minimize them? That’s incredibly rare, and I’m very grateful. We never approached private financiers.

Anna Rose Holmer: I had heard about the Venice Biennale program from the first year it existed, and it seemed like such an exciting way to make a film. So even before we formally applied I was thinking about the strengths and style of that program when I was thinking about The Fits. It was our first choice for financing this film and the only way we actually went about it. The Fits was entirely grant supported, our key funder being the Venice Biennale program. In addition to financing, they were mentors and provided development support for the film, and they really championed experimentation through the process. The support wasn’t just project based but the artist behind the project; they made sure that the film was satisfying other artistic needs and was taking risks. Besides just being a finished film, was it furthering my ideas about cinema? Was it challenging to me as a creator? And I think that’s very rare. So that’s why I wanted to develop the project with them. And then the Sundance Institute came on, and Cinereach and Rooftop. With all of those partners, it was always about: how do we amplify the risk and challenges that you’re facing in an exciting and constructive way and not minimize them? That’s incredibly rare, and I’m very grateful. We never approached private financiers.

H2N: That’s a good way to avoid the problem, because if you had gone the private equity route, we probably wouldn’t be talking right now!

ARH: No.

H2N: Is the Biennale process similar to other grants? Is there a lot of writing involved to present your approach and vision in as detailed a manner as possible, along with visual samples?

ARH: They’re really open to what your materials can be. For me, I wasn’t sure I wanted a traditional screenplay when we first went into the development process. I collected my ideas using Tumblr, so [I made mood board collages]; it was a collection of dance videos, cell phone videos from teenage girls. All of those textures eventually found their way into the traditional text work we ended up doing. But when I was pitching it, it was much more abstract and open, and I was excited that they connected to that style of development.

H2N: It’s funny, that was my next question. To me, so much of the film felt like it was borne out of ideas, whether visual or emotional, as opposed to a traditionally written script.

ARH: Funnily enough, it does read like a traditional screenplay because it ends up being that. But there is almost no dialogue in our script; it’s a list of choreographies, small movements. We formatted it in a traditional way, but it certainly doesn’t rely on a traditional three-act structure. And a lot of that came from the fact that Saela Davis, my editor, Lisa Kjerulff, my producer, and I co-wrote the script. We talked a lot of it out, we acted it out, we moved. We really approached it from a visual and kinetic point-of-view from the beginning. So if you were to read it, that’s what it’s like. It’s a description of action, really. Like, I don’t know what the screenplay is like for Mad Max. It’s really short, right? [both laugh]

ARH: Funnily enough, it does read like a traditional screenplay because it ends up being that. But there is almost no dialogue in our script; it’s a list of choreographies, small movements. We formatted it in a traditional way, but it certainly doesn’t rely on a traditional three-act structure. And a lot of that came from the fact that Saela Davis, my editor, Lisa Kjerulff, my producer, and I co-wrote the script. We talked a lot of it out, we acted it out, we moved. We really approached it from a visual and kinetic point-of-view from the beginning. So if you were to read it, that’s what it’s like. It’s a description of action, really. Like, I don’t know what the screenplay is like for Mad Max. It’s really short, right? [both laugh]

H2N: How does that connect to your phenomenal use of sound? I think what’s electrifying people so much about this film is that you didn’t sacrifice one filmmaking component for another here. Everything is firing on all cylinders. Was your focus on sound design there from the very beginning as well?

ARH: It actually [started in] the script phase because sometimes we would write scenes and we would circle entire pages and say “this is off-screen; we’re not actually seeing this but it’s important to the experience for the audience.” We knew we were going to rely heavily on sound design, and so actually our sound designer came on before we started shooting. We had a strategy meeting with Chris Foster, our sound designer, Saela Davis, our editor, and our production sound recordist Gillian Arthur, and me. We talked about how sound was going to be used, and that was one of the most exciting conversations. I’d never been part of a conversation like that for any other film. Some of it was just the implications of what it would mean to be on set and how we were going to record. Like, we did a lot of stereo recording so that we could mix that in a 5.1 setting to really put you in the center of the room with all those bodies around you. And some of it was also just about, okay, so our script day might be focused on these visual things, but in addition to that we need to get this audio material to really build out this scene, so what is that going to look like just from a production standpoint? Sound was super integral and having Chris Foster be part of the discussion and strategy going into production was exciting for me.

ARH: It actually [started in] the script phase because sometimes we would write scenes and we would circle entire pages and say “this is off-screen; we’re not actually seeing this but it’s important to the experience for the audience.” We knew we were going to rely heavily on sound design, and so actually our sound designer came on before we started shooting. We had a strategy meeting with Chris Foster, our sound designer, Saela Davis, our editor, and our production sound recordist Gillian Arthur, and me. We talked about how sound was going to be used, and that was one of the most exciting conversations. I’d never been part of a conversation like that for any other film. Some of it was just the implications of what it would mean to be on set and how we were going to record. Like, we did a lot of stereo recording so that we could mix that in a 5.1 setting to really put you in the center of the room with all those bodies around you. And some of it was also just about, okay, so our script day might be focused on these visual things, but in addition to that we need to get this audio material to really build out this scene, so what is that going to look like just from a production standpoint? Sound was super integral and having Chris Foster be part of the discussion and strategy going into production was exciting for me.

H2N: So far, you seem to be providing the checklist for making a really good film! [ARH laughs] Was there a lot of trial-and-error in post once you got to that stage? Something that you thought would work but didn’t, or the other way around?

ARH: We really struggled to find what Toni’s internal space sounded like. We listened to a lot of medical recordings, sonogram stuff, to find out, like, what does it sound like to be in a body? Toni goes into this very internal state when she’s exercising in particular, and I think at first it was too noisy. Through trial-and-error we found this great balance. It was really about stripping away sounds and having this kind of peaceful, cavernous space where only a few sounds make it through all the layers. And that was what was really exciting. And then music also, we played around. The idea of playing was so important to this film. I think it was about creating an environment where my collaborators felt like they had a voice, but also felt like they could experiment and fail. And that, for me, was really important to protect. I think that often there’s this kind of feeling that if you make a wrong step then everything collapses, and I think it’s the opposite. You can’t build something that’s very strong unless you play and experiment and make errors and grow that way, and I think that trying to invite your collaborators into a space of experimentation was something we were very mindful of every step of the way.

H2N: And I’m sure that by having the people who were paying for the film be in full support of this approach also helped to prevent the over-thinking and second-guessing that might otherwise have arisen. So you could have a terrible idea and not get insecure about it.

ARH: Exactly. We definitely had terrible ideas through the process! [H2N laughs] But we were able to hold each other accountable as a team and it did feel very empowering to make a film that way.

H2N: Obviously everyone is praising Royalty Hightower for good reason, but the filmmaker in me was perhaps as impressed by your direction in the group scenes. The individual interactions are authentic and great, but the choreography in those scenes—I’m not talking about the dance choreography—didn’t feel “directed” to me, in the best way possible. How did you pull that off?

ARH: It was a lot. There were a lot of bodies. [both laugh] But they’re all dancers. Or boxers—the guys were equally generous and incredible. The boys are at the junior Olympic level and the girls are at the national level as dancers, so it was actually very easy to approach everything as choreography. Blocking was just a very shared language, and so we were always trying to make very dynamic tableaus with bodies that always pointed your eyes to Toni. I think of Kurosawa or Bresson, who used the group dynamic or a group setting as an externalization of the main character’s internal state. That’s what we were always trying to do. Like the girls running down the hallway around Toni. That’s an expression of her and her state-of-mind. As performers, they all understood dance, and so when we talked about movement, however big or small, we talked about it as choreography and it was very comfortable. Some of my favorite moments are these background actions of body mirroring and pairing two people together and saying, “Okay, you have to do exactly what the other one is doing,” and like these little, hidden expressions that I think add up to something very significant. It was a joy to work with them.

ARH: It was a lot. There were a lot of bodies. [both laugh] But they’re all dancers. Or boxers—the guys were equally generous and incredible. The boys are at the junior Olympic level and the girls are at the national level as dancers, so it was actually very easy to approach everything as choreography. Blocking was just a very shared language, and so we were always trying to make very dynamic tableaus with bodies that always pointed your eyes to Toni. I think of Kurosawa or Bresson, who used the group dynamic or a group setting as an externalization of the main character’s internal state. That’s what we were always trying to do. Like the girls running down the hallway around Toni. That’s an expression of her and her state-of-mind. As performers, they all understood dance, and so when we talked about movement, however big or small, we talked about it as choreography and it was very comfortable. Some of my favorite moments are these background actions of body mirroring and pairing two people together and saying, “Okay, you have to do exactly what the other one is doing,” and like these little, hidden expressions that I think add up to something very significant. It was a joy to work with them.

H2N: Was your crew large enough for you to have a specific person on background, like a 2nd or 2nd-2nd?

ARH: I had a 1st (Annalise Lockhart) and 2nd AD (Jack Grimmett), and we had three choreographers on set, so I always felt like I had support and the girls were also just very respectful of the process. We didn’t actually have so many days were there were 45 people. Only a few of the days were that big.

H2N: I imagine you were shooting off-season to get the location access?

ARH: It’s actually a community center in the West End, and we shot mostly around spring break and weekends when the community center was closed. We did have quite a few days that were active community center days but the bulk of the shoot, and especially the big scenes, were during spring break.

H2N: You mentioned the scene of the girls running around Toni. My first thought was that those kids must have had so much fun shooting that when you called action! How many takes of that did you do?

ARH: We actually had to tone that down a little bit. It was a little bit too wild. [H2N laughs] Royalty’s body was being bounced back and forth but too much. The current was too strong. We had to add a bit more choreography to it to get the crosses right and really make sure that we could maintain that centering with Toni’s character and not lose her too much to the left or right. So I think it took about three or four takes for us to get that right, and then a couple to polish it.

H2N: So many films are longer than they need to be. I’m not even talking about the bloated two-hour-and-forty-minute summer multiplex movies. I’m talking about the low-budget indies that always seem to land at the 90-to-93-minute mark. I’ve become totally suspect when I see that run time before even watching an indie movie anymore. The Fits clocks in at 72 minutes, which feels perfect to me. I guess this might go back to your financing situation, which didn’t put any parameters on you whatsoever, but I’m wondering if there was an assembly or version of this that was much longer?

ARH: It was always very lean in the way that an athlete is very lean. Like, you only carry the body mass that you need, and anything extra becomes actually a hindrance. There are almost no scenes that made the cutting room floor. We did have a lot of [one-takes] and so Saela did shave off quite a bit at the beginning and end of shots. A two-minute take might work in isolation but 45 minutes into your film the timing’s off, you know? And that becomes a 45-second shot instead of a two-minute shot.

ARH: It was always very lean in the way that an athlete is very lean. Like, you only carry the body mass that you need, and anything extra becomes actually a hindrance. There are almost no scenes that made the cutting room floor. We did have a lot of [one-takes] and so Saela did shave off quite a bit at the beginning and end of shots. A two-minute take might work in isolation but 45 minutes into your film the timing’s off, you know? And that becomes a 45-second shot instead of a two-minute shot.

I would rather have an audience leave a film wanting to live in that world for longer, wanting to watch it again, than the other [feeling]. So often I’m on the other side of it where I’ve gotten what I need. That doesn’t mean you’re not allowing for breathing or patience or quiet moments, because we certainly have that, but it was always about what is necessary and only necessary. And being not precious about it. I think that one of the things I’m so excited about with regard to the future is that things are seeming to fit the length and format they require as a story, looking back at what your story is and not these external definitions of what is “required.” I do think that if it hadn’t been made in this grant way, we probably would have been pressured into lengthening it [in a way we didn’t want].

H2N: Okay, that’s all I’ve got. But I think in this brief amount of time you just described how to make a kick-ass movie!

[At this point, I stopped recording, but Anna wanted to put in one more plug for Royalty Hightower, whose praises she said she cannot sing highly enough.]

— Michael Tully