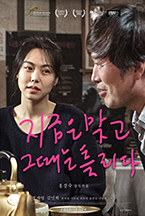

RIGHT NOW, WRONG THEN

(Right Now, Wrong Then receives its U.S. premiere this Friday, October 9, as part of the New York Film Festival. Additional screenings will follow this Saturday and Sunday. Go here for more information.)

The South Korean writer/director Hong Sang-soo is one of my favorite contemporary filmmakers, even though I can’t always remember which of his movies I’ve seen. In my defense, it’s not easy for even a professed fan to keep up with his output: seventeen features and a handful of shorts since his debut in 1998, and he’s working at a faster pace now than when he started. Furthermore, the same elements appear again and again in his films, a deck of cards that he shuffles and re-deals in ever-new combinations. With some artists, this might be a sign of inspiration run aground. With Hong, as with Ozu and Rohmer before him, the opposite is true— the repetitions-with-variations seem like outpourings from an endlessly bountiful, effortlessly original talent. It’s like watching a tree come into flower every spring: only an ingrate would complain that the leaves were green last year, too.

You go to see the new Hong, and you know certain things will turn up. There will be men falling into sticky romantic and sexual entanglements with young women. (Usually these men are filmmakers, writers, artists, or professors; increasingly, they’re middle-aged.) There will be ruthless but uproariously funny explorations of the male ego in all its sorry, self-pitying splendor. And of course, there will be ingenious structuring devices: stories within stories, scrambled chronologies, unreliable narrators, doublings, triplings, quadruplings. These structural experiments are carried off with a light touch and a playful, inquisitive spirit, providing the viewer with alternate perspectives, transforming the straight road of linear narrative into a garden of forking paths, a puzzle with multiple solutions.

In Right Now, Wrong Then, which has its U.S. premiere this week at the New York Film Festival (the eighth of Hong’s features to screen at NYFF), the structuring idea is simple but its consequences characteristically complex. Ham Chun-su (Jung Jae-young), a much-admired art-house filmmaker, travels to Suwon, a city just south of Seoul, for a Q&A following a screening of one of his movies. Arriving a day early, he takes in the sights and meets a pretty, earnest, soft-spoken young painter named Hee-jung (Kim Min-hee). He visits her studio and looks at her work; they talk, get drunk, and end the night hanging out with friends of hers at a cafe, before finally parting ways. The next day, after his Q&A, Chun-su prepares to return to Seoul.

That’s the story Hong gives us. But he gives it to us twice—two versions, each running about an hour, one right after the other. (Reportedly, he screened a cut of the first version for his actors before they shot the second version.) At first, the differences between the two seem superficial: minor variations in dialogue, in nuances of performance, in the blocking of actors and the framing of shots. Before long, more significant discrepancies begin to emerge. Throughout the film’s first half, Chun-su dodges and dissembles in his dealings with people, hiding behind platitudes and false flattery. In the second, he’s painfully (and hilariously) blunt, honest to the point of being utterly insensitive. These divergent character traits, revealed to us only gradually, ripple outward, affecting how Hee-jung and others respond to him. (Here’s a mild spoiler, and a wise insight on Hong’s part: Hee-jung is ultimately more receptive to the jerk who’s straight with her than the jerk who pretends to be a nicer guy than he really is.)

And yet, there’s no simple thesis statement to be drawn from this. The two versions (of the story, and of the main character) match up in most of their essentials. The pleasure and the interest in comparing the two halves come in observing the small shifts of emphasis—how a piece of backstory shared with us at a crucial moment alters our understanding of someone’s behavior, how the measuring-stick of our sympathy slides back and forth based on a character’s slightest turn toward kindness or cruelty, enthusiasm or indifference. I suspect that Right Now, Wrong Then will offer up more meanings on repeat viewings, but also that much will remain mysterious. Hong loves his puzzles, but for him people are the true puzzle—the unsolvable, infinitely fascinating mystery.

— Nelson Kim