SO, YOU WANNA GET TROMATIC? MATHEW KLICKSTEIN’S NEW BOOK LLOYD KAUFMAN : INTERVIEWS IS COMING SOON!

Frequent Htn contributor Mathew Klickstein is quite a busy guy. His latest book is a compilation of interviews from modern-day schlock king and President of Troma Entertainment, Lloyd Kaufman. Mathew reached out to see if we’d help spread the word on his book and we of course said yes. What follows is an attenuated introduction to the forthcoming LLOYD KAUFMAN: INTERVIEWS via University Press of Mississippi, coming in February 2025.

Take it away, Mathew…

“Insulting art (like insulting the audience) is an attempt to head off the corruption of art, the banalization of suffering.”

– Susan Sontag, Introduction to Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings (1973)

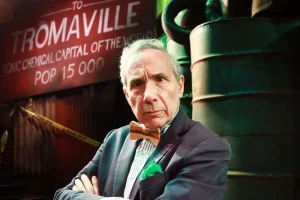

Lloyd Kaufman (b. 1945) is first and foremost one of the last great peppermint stripe-suited, bow-tied showmen and entertainers in the Jewish-American vaudevillian badchen style. He is a pioneering (if not the pioneering) force in contemporary filmmaking’s postmodern paradigm of “schlock,” a stridently DIY-based genre-bending mélange of over-the-top graphic violence/horror and engagingly fourth wall-busting Brechtian meta-humor in the vein of “camp,” typically infused with a prole-ish punk rock ethos.

Kaufman is also cofounder and president of fifty-year-old B to Z movie studio (quite possibly the longest-running independent studio in cinema history) Troma, and writer-director of more than fifty feature-length films of his own.

And he will likely be dead by the time our book is at long last published.

We have to face the brutal, pragmatic realities here twofold. 1) As poet Robertson Jeffers’ stoical “Be Angry At The Sun” (1941) would nudgingly remind us, it’s simply not worth investing any energy into frustrations stemming from the long acknowledged snail’s pace of book publishers these days (at least those not in the panicked throes of flailingly rushing out some extremely topical newsy tome, trending “influencer” and/or celebrity and/or media/political pundit’s memoir/autobio/bio, or yet another sequel to some latest lusty YA novel/fantasy/graphic novel). This is especially true viz. those released in the academic/scholastic/university marketplace.

2) Despite having become a vegetarian in the early 2000s with daughter Charlotte after reading Eric Schlosser’s impactful j’accuse Fast Food Nation (2001), which also inspired Kaufman’s own Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead (2006), American independent cinema’s most irrepressible renegade takes notoriously terrible care of himself.

Exhibit, regardless his lifelong claims toward Eastern inspiration from Taoism and Zen, Kaufman’s easily observable and well-documented neurotically compulsive driving of himself (and many of those around him) unrelentingly up-the-wall with all manner of stress about his place in the cinematic pantheon, the dozens of live-event and multimedia projects forever swirling around his general proscenium, and just about every possible global conflict happening all at once.

Meanwhile – at nearly eighty at the time of this writing – consider Kaufman’s miraculously and perhaps dangerously jet-setting to anywhere and everywhere he can go to pitch, produce, support, and promote both his own ever-growing slate of filmic concoctions and those of his hundreds of acolytes who are only too aware that Kaufman, like some demented cross between an ejaculative birthday clown and “Crazy Eddie”-esque used car salesman, will appear to huckster when asked for the mere cost of even the lowest-grade travel accommodations, lodgings (air mattress/couch accepted), and Del Taco/Pizza Hut fare (just ask South Park [1997- ] creators and filmmakers behind Troma’s own Cannibal! The Musical [1993] Trey Parker and Matt Stone).

While wrapping up the final trappings of this omnibus of interviews, feature articles, Q&As, commentaries by Kaufman himself, etc., I was texting with the man probably best known for his thrusting upon the world stage the iconic The Toxic Avenger (1984) about this unfortunate revelation.

“We’ll probably have the book launch during your eulogy, Lloyd” I (tongue-somewhat-firmly-in-

Lloyd Kaufman

Kaufman’s noted admiration for the works of Shakespeare (having “adapted” two major works to date – Tromeo & Juliet [1996] and #ShakespearesShitstorm [2020] based on The Tempest; and his constant touting of Hamlet as “101 Moneymaking Screenplay Ideas” as well as his repeated incantation of that play’s “To thine own self be true”) makes it ever the more potently apropos to recall, “’Many a true word hath been spoken in jest,” from the Bard of Avon’s King Lear.

Despite the fact that you will read Kaufman’s constant parroting of “To thine own self be true” no less than four times throughout the pieces in our book, it’s this latter Shakespearean adage that may far better articulate if not encapsulate both Kaufman’s consistently contradictory and nuanced Weltanschauung and his similarly dualistic decades-in-the-making Gesamtkunstwerk comprised of the most outrageously taboo-demolishing goofiness (inspired as he is by Tom and Jerry [1940 – ]) and the most disruptively agenda-pushing agitprop (equally inspired as he is by 1960s counterculture godhead sociologist C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite [1956]).

I can think of no better example of Kaufman’s astonishing adeptness at conflating outlandish absurdity with devastatingly incisive (if not stunningly prescient) polemics than that of a particularly fractious fragment from his 1992 profile in the British sociopolitical magazine The New Statesman (with the subhead inquiring if “Troma films can save the world with an old-fashioned watch”):

“The profligacy of film-makers spending US$100 million on special effects seems slightly disgusting at this time. We’re moving away from the form-over-substance ideas of recent years. It’s for this reason we made the manufacturer put a traditional, circular face in the Toxie watches [the US is awash with “Toxibelia”], rather than the usual digital ones. We wanted to encourage kids to grow up, viewing time as a circular continuum, rather than as a linear construct. If it’s linear, you want instant everything, and you grow up to be a grasping, greedy, thoughtless person, a big fat slob with bushy eyebrows and a tendency to fall off boats—that’s where that leads to. With the Toxie watch, indicating time as a continuum, kids learn to take a long-term view; they work hard, they save their money, they have a full and fruitful life, and Troma eventually becomes a major studio, strictly on its own terms.”

And there we are. Is Kaufman kidding here? Is he vaunting some kind of pre-established, prepackaged, “marketable” “loose cannon” persona for the purpose of breaking through the “white noise” of today’ blaring media maelstrom? Or … do we need to “read between the lines” of what Kaufman is “actually” saying, and the very valid points he’s making about the utter obscenity of how the mainstream movie scene operates but of the general Western societal sensibility writ large?

After all, what “reading between the lines” do we need to execute here? The man says exactly what he means, right upfront and without any suppression of his typically splenetic umbrage at, as he himself would say, how “fucked up” “everything” is these days (even down to, say, how children are taught to understand the very system of Time Itself) … before going on to say that some tiny underground film company like his can invest the resources properly into ensuring wristwatches they merchandise from a popular film franchise in such a way as to perhaps, yes, “save the world.” Truly, then, what’s so funny about that?

Kaufman, Toxie and Mathew Klickstein

It’s long been my feeling that the best way to insert pertinent and impactful sociopolitical rhetoric into the zeitgeist is first through those cultural realms that are not much taken seriously (and thus left alone to their own devices, unexpurgated). We saw this in early punk rock and hip-hop music, for example. Nobody in the mainstream media took these idioms seriously (if they even knew about them, to begin with), and hence they could “sneak in” much that could not be said elsewhere.

Was there any more apt and nuanced analysis of the outlandishly contentious 2016 Presidential Election season than that which was broadcast through the long-running continuing story of South Park (1997 -)’s twentieth season? Show creators/runners (whom, as mentioned, achieved their start under the Troma aegis) were able to “get away” with what they were saying (including a relentless fusillade of “truth bombs”) in those provocative episodes because, well, “It’s just South Park.”

So too can we witness the same exacted by science fiction godhead and the man responsible for such vibrantly prescient works as Fahrenheit 451 (1953) thunderingly railing at an audience of young fanboys (and a small smattering of fangirls) at the inaugural San Diego Comic-Con in 1970 that the only national publication worth reading is not anything from the “conservative press” nor the “liberal press” but rather – “Goddamn it!” he proclaimed – the cartoon-based humor magazine (and one of many early influences on Kaufman and Troma) MAD. To Bradbury, MAD was more than a jokey underground rag of sorts. No, it was NEWS. And the only News worth reading during one of the US’ most volatile time periods in contemporary times, at that.

As Southern Gothic writer and vehemently contrarian moralist Flannery O’Connor used to say, people are not seeing and listening to what they need to see and listen to these days, and thus they must be awakened through an electrifying and stimulating jolt that some may find uncomfortable to experience. How otherwise to awaken them from their befogged torpor?

Furthermore, we must acknowledge the vital essentialism of Kaufman’s rather ascetic filmmaking style (some, including frequently Kaufman himself, may dysphemismistically use the word “crappy”). This goes to the point, which he makes very often, that to best represent authentically the rather (let’s use it again here) “crappy” state of affairs of the Kafka-esque modern-day world in which we all are consigned to exist, so too should Kaufman’s stylistic expressions be, well, at times crappy too.

Think here of Marshall McLuhan’s aphoristic “medium is the message” structuralism that encompasses the creation (and promotion) of such early postmodern and extremely brutalizing aesthetic systems as: Brazilian scribe Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed; Cuba’s Imperfect Cinema; underground comix a la Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, Frank Stack’s The New Adventures of Jesus, and Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix; the French Nouvelle Vague (along with “new wave” cinema of Iran, Germany, Britain, Czechoslovakia, etc. — all of which was portended and galvanized by the raw, cinéma vérité sensibilities of postwar Italian neorealism, of course); Detroit-based punk rock as exemplified in the very machine/industrial (think of the ubiquitous car manufacturing of the time and place) music of the MC5 the Stooges; and the first novels of manically irascible novelist Hubert Selby, Jr. who would refer to his body of work as “a scream looking for a mouth.”

It’s worth noting that all of these creative movements first burbled up out of the mucky ground water of the same tempestuous times that Kaufman first got going with his feature film productions. All soon leading to such next-generation creative endeavors as: hip-hop, the New York “No Wave” arts/music/film scene (buttressed by the deeper underground Cinema of Transgression), and eventually so-called “grunge” rock (with exemplar Nirvana front man Kurt Cobain referring explicitly to the “scream looking for a mouth” notion every time he spat his shrieking lyrics into a microphone).

“It seems to me that the modern painter cannot express this age — the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio — in the old forms of the Renaissance or any other past culture,” abstract painter paragon Jackson Pollock pronounced during a 1951 radio interview. “Each age finds it own technique.”

We are here expanding on the oft-repeated modality of mid-century jazz and blues music (and its somewhat unlikely inheritors in bebop-influenced Beat poets and standup comedy progenitors Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl, et al) being not only products of their environments but also, to harken back to McLuhan, a message of those environments.

“Do you think that one can allow less literary authenticity and effectiveness to a poem which is imperfect but filled with powerful and beautiful things than to a poem which is perfect but without much internal reverberation,” actor, writer, and theater theorist Antonin Artaud asked in a letter to publisher/editor Jacques Rivière in 1923.

It is the drive and passion for expression — the scream searching (in vain?) for a mouth — that Artaud is ranting about here. Hence Cobain’s own explanation of what drove him to the idiom of punk rock as a young seeker: the grime and grit of its impressions bursting with an implacable vitality so eruptive (and perhaps orgiastic) that any sense of formalistic propriety was rendered irrelevant. It didn’t matter how “good” something was, only how impassioned its creator, how brutally raw and “real” his or her passion could be relayed through the creative process.

As Kaufman will elucidate in more than one article ahead, Troma and he so often traffic in viscera-splattered horror because, well, our collective society is pretty gorily horrific (and often grotesquely horrible). To be honest about this — which the frenetically impulsive/compulsive Kaufman can’t possibly avoid in his thoughts, expressions, interviews, and certainly filmmaking — he has to maintain that horror/horribleness in everything he does. Or as he much more eloquently puts it:

Vintage Lloyd and Toxie

“I thought it was important to start Terror Firmer with some brutal moments, because to a certain extent that is what American society is: brutal. The reality of American life is constant racial and sexual violence. My movies are a reflection of that. From The Toxic Avenger on, we have been involved in fighting hatred and violence and the puritanical dictatorship in America. It’s always been there in our movies and these important buttons have to be pushed.”

On a more personal and introspective bent, Kaufman’s seeing the world through the eyes of someone who grew up in the realm of the very “elite” that he’s forever railing against, referring to his youthful background in upper crust Manhattan as “the ultimate bourgeois. I went to Trinity School in New York and Yale University.”

His parents would throw lavish parties that were often populated by the likes of Broadway star Elaine Stritch. Montgomery Clift came by at one point. Oliver Stone, who too would have a rather intimate view of the “elite” world while spending his entire career deconstructing and disrupting it with profound apoplexy, was a nearby boyhood friend.

This intimate connection with the bourgeois society Kaufman grew up with and within was then short-circuited by the “Red diaper baby” worldview endowed by his grandmother, who was a kind of “eat the rich” pseudo-rabble rouser in the mold of an Emma Goldman, pushing her pubescent grandson early on to despise his upper crust/jet-set society for its hypocrisy, venality, cupidity, and sociopathic cruelty.

And, by god, Kaufman did despise that society and says his grandmother still is to this day remains one of his most potent influences on both his filmmaking and the way he leads his “damn the man” lifestyle.

However, this apoplexy at bourgeois duplicity (manifested by what he sees as the twin marplots of pharisaic “limousine liberals” and puritanical Reaganites — two sides of the same very expensive, multinational conglomerate-forged coin) is tempered in both his filmmaking and worldview by the other major influences with which he grew up — aspirational Broadway musicals, buoyant animated cartoons and idealistic comic books.

Hence the visceral colorfulness (both literally and figuratively) in his work. Hence the playfulness. Hence the hope and optimism that still exists under the surface of the muck and mire. Hence the “geeks shall inherit the earth” agenda of virtually every one of Kaufman’s directed pictures and stories.

The freaky weirdo misfits and underdogs in his movies may be (sometimes literally) shat upon by the bullies and villains and society itself. But they can still have some uproarious good times, find friends, find love, and ultimately succeed in defeating that same vile villainy nearly every time by picture’s end. Doing so through a world that may be odious, but also infused with an effulgent, Mondrian-esque brightness (and boldness that at once states: “We are here, TOO!” and “Look at THIS!”!).

Charlie Chaplin and Mel Brooks — both having, too, profound influence on Kaufman, particularly the former — always said (and promulgated in their respective works) that one of the best ways of dealing with society’s horrors and hypocrisy was through irreverent, nose-thumbing ridicule. So it is with Kaufman’s Troma.

It was in fact the aforementioned “Toxie clock saves the world” interview segment that I sent to Kaufman over text that kicked off what may, on the onset to the uninitiated, would appear an exceedingly morbid conversation about how Kaufman may very well not be around to see the publication of this very book whose production he’s been supportively aware (hence his granting me of an interview as coda exclusively for it). Read onward, though, and you’ll notice – if you can’t already tell from his films (both those he’s made himself and those by Troma’s scads of cultish congregants) – “morbidity” is but one more bourgeois, elitist, and – most sinful of all in the mode of Oscar Wilde – boring taboo which downright requires exploding.

Regard how, once again as almost pious incantation, throughout these interviews Kaufman proclaims he’s prepared to “blow my fucking brains out” with a pearl-handled derringer he allegedly keeps at all times stowed away in his desk.

And yet, even if his thinly-veiled blind independent filmmaking doppelganger “Larry Benjamin” (played, for those who still think there’s any need to “read between the lines” with any of Kaufman’s output, by himself) in Terror Firmer (1999) also pronounces that he’ll shoot himself in the head if things keep not adhering to his needful sense of how things are done properly (on the set of, here we go again, Troma’s upcoming fourth installment of The Toxic Avenger) … there’s inherent here that customary Kaufman-esque dualism of “is he kidding/insane? Or is he frighteningly serious? Is he trying to get attention? Or should we be calling the cops/mental care facilities?”

The joke may be on us here, though – because, as long as I’ve known Kaufman (more than half my life as a young, peripheral Troma-ite and longtime chronicler of the film maven’s life and work for a variety of previous publications) – he’s always been calm, collected, sweet, gentle, generous, and absolutely, positively in love with his fans (even if some of them scare the hell out of him), his staff (even if some of them piss him the hell off), his films (even if he, as you’ll read ahead, he denounces them as candidly as he may praise them), and, most profoundly, his three now-grown daughters and lovely and always-in-his-corner wife of fifty years (whom he married, in what Jews such as we may refer to as rather bashert, the same year he started Troma with his other much-loved, five-decades partner, Michael Herz).

“I might scream about the big issues, like war or Hillary Clinton or Pathé-is-the-Devil and all that,” Kaufman explains in a 2001 Q&A for the Dutch fanzine Schokkend Nieuws. “But the reality is that my family is much more important. I’m more proud of the fact that I’m still married to my wife after twenty-five years, that my kids are reasonably normal and happy, and that I’m still working with the same business partner after all these years, than getting awards from festivals.”

This is also something that Kaufman repeats, almost as though reading a script word-for-word, in various other profiles and interviews curated here, including the recent 2017 piece for Paste in which he updates the “twenty-five years” milestone with “forty-three years.”

Now, does this sound like someone who is truly so explosively upset at everything and everyone around him that he’s ready to end it all in one final grand exhibition of just how “crazy” he may be? Kaufman seems to be having way too much fun for all of that rot.

Granted, in that same Schokkend Nieuws/Flashback Files piece, there’s a close-up of a freakishly manic looking Kaufman holding a gun to his temple. But, still, I’ve known and worked with Kaufman and been close enough with his ever-changing lineup of Troma Team members (and those who have clung on to the Tromatic rollercoaster ride by the fingernails as long as I, if not longer) to know that Kaufman’s much-repeated “I’ll blow my fucking brains out!” mantra is as much a quirky catchphrase as, say, his continuous (and, certainly, life-affirming) proclamation: “LET’S MAKE SOME ART!”

Because, you see, Kaufman is incredibly consistent and he’s incredibly affected by James Joyce’s “ineluctable modality of the visible” at the same time. His life may seemingly not change as per Too Much Coffee Man creator and New Yorker cartoonist Shannon Wheeler’s “same crap, different flies” assertion a la the Stoics’ (to some, nightmarish in the Sisyphean sense) concept of “eternal recurrence” (popularized centuries later by no less than Friedrich Nietzsche).

But his perception of what’s going on around him may nevertheless vacillate according to whom he’s speaking with, how he’s feeling, or (as we see in the Reddit AMA included in our omnibus or in a particularly embarrassing moment from one of Troma’s many behind-the-scenes feature docs, Poultry In Motion: Truth Is Stranger Than Chicken [2008]) whether or not a bad burrito is causing him to dash to the washroom.

This is how Kaufman can stay intransigently unmoved in the macrocosmic way he proceeds and speaks of himself, his work, and society at large, while at the same time, on a microcosmic level, can seem all over the place in his thoughts and emotions. Truly, it’s chaos theory’s “scaling” component in motion: On the outset, everything remains the same; but zoom in a few thousand clicks, and it’s utter madness. (Or vice versa.)

This, of course, harkens back to Kaufman’s professed Taoist leanings based on his having been a Chinese major in college at Yale and his influence – again, constantly referenced in the articles ahead – of living via the inviolable mechanism of “Yin and Yang.”

A more recent shot of Kaufman

Let’s set aside his “blow my fucking brains out!” catchphrase for now and focus on “LET’S MAKE SOME ART!” (the tagline, incidentally, to the as-mentioned-meta feature film Terror Firmer [1999]).

In Jill J. Lanford’s 1983 piece appropriately titled “TROMA Films: They’re Not Art, But They Make Money,” Kaufman professes: “Going to a TROMA film is not an art experience, and it’s not supposed to be. We make movies that appeal to a young audience that is looking for a few laughs, a thrill or two and some mild sex. That’s it. We don’t even try to appeal to your mind – just your raunchier senses.”

True, this was back in the earliest days of Kaufman’s (and, by proxy, longtime partner Herz’s) oeuvre being known as being built upon soi-disant “sex comedies.” But, still, how serious is Kaufman really being when he’s not only bandying around the rather pedomorphically idiomatic “LET’S MAKE SOME ART!” but also proclaiming something like this: “Look, when Van Gogh made his paintings, nobody understood it. He had to cut his ear off. I don’t know about a more influential artist than Van Gogh. Troma is like Van Gogh. But the difference is that Troma has been lucky enough to find an audience while we’re alive. We can support ourselves by our movies. Van Gogh did not have that luck.”

To make matters more confusing to the investigative mind, Kaufman follows up a seemingly uber-pretentious statement of how he would put Troma’s work in the same ring as Van Gogh’s with: “On the other hand, [Van Gogh] didn’t have to worry about distribution. He had a rich brother to support him, so … If I had a rich brother, I probably wouldn’t have bothered doing anything. But I didn’t have a rich brother when I started. Now I do. My brother is very rich. He’s made a big business of bread.”

Har har? But, wait … Fifteen years later, in (what would become an incredibly viral) James “The Angry Video Game” Rolfe interview with Kaufman, we see the maverick filmmaker once again speaking of his work in the same breath as that of Van Gogh’s (not to mention – are you serious?! – Stanley Kubrick):

“Well, it’s an art form, and in the same way that Picasso painted or Van Gogh painted, you want to give something in your soul to express it. You know, Kubrick spent ten years on [the un-produced] Napoleon. He had a project called Napoleon, and he had a file card … There’s a Kubrick show somewhere, and it’s in LA, I think, and he had file cards for every day of Napoleon’s life. He spent … obviously obsessed about it.”

Oh, and guess what? Kaufman also completely invalidates his repetitive declaration that what he is most proud of in his life is his family in the same interview by disclosing in the same interview later, “I mean, again, I think you have to be a bit eccentric. I know that in my own personal life, I put filmmaking way ahead of my wife and family, and I regret doing it. But there was no other way to make the movie.”

Yes, Kaufman may repeat himself (often word-for-word, even when it comes to a groaningly Henny Youngman/Milton Berle-esque joke-telling style). And then cross out what he’s said in some kind of (often very self-aware) dadaist découpé style a la Brion Gysin and Jean-Michel Basquiat. And then repeat again (in all fairness, he does right after that last statement in Rolfe’s interview add, once again, how proud he is of maintaining the same wife, business partner, and even childhood friends he’s had for decades).

Yes, Kaufman has been (knowingly?) playing this randy game of dialectics for so long that it does become virtually impossible to recognize when Kaufman is being serious, when he’s being facetious, when he’s being a bloviating showman, and when he is being a forward-thinking prophet.

The impishly diminutive Kaufman would likely grant us a Mel Brooksian nisht getoygen shrug and remind us that, as a spiritual protégé of Charlie Chaplin (both in artistic sensibility of combining the serious with the live-action cartoon and in the financial savvy of keeping his own film negatives to own the distribution/exhibition rights to his pictures), he’ll put it to the Tramp who (as became one of Chaplin’s repeated catchphrases) famously responded to the same question, “If you want to know me, watch my movies.”

Book available in hardcover, paperback and e-book editions wherever you purchase books or through the UPM website.

More on Mathew Klickstein including details about his forthcoming graphic novel DAISY GOES TO THE MOON illustrated by Rick Geary and out through Fantagraphics in January 2025: www.MathewKlickstein.com

– Mathew Klickstein