25 YEARS OF THE SF SILENT FILM FEST

Undoubtedly the finest showcase of silent-era films in North America (and, arguably, second only to Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in the entire world), the San Francisco Silent Film Festival returns to in-person presentations for its quarter-century anniversary! Twenty-five years already? Actually, somewhat longer (since the first edition of the festival back in 1996) and somewhat larger: from a single day back then to seven in this edition. [Its long-anticipated reappearance at the Castro Theatre ideally will not end its occasional virtual programming, undoubtedly the best film-related tether throughout the pandemic.]

If you have never seen pre-1930s cinema—which, given where you’re reading this sincere appreciation, is perhaps unlikely—it would be essential to note that silent films were never intended to be silently screened. Silent film exhibitions were always presented with an accompanist.* When these films were new, that could range from a lone individual at a piano or organ or possibly a small ensemble or even a full orchestra (and occasionally a narrator or Benshi as well). SFSFF screenings include all-of-the-above: individual performers Wayne Barker, Frank Bockius, Guenter Buchwald, Philip Carli, Stephen Horne, Paul Miller [aka DJ Spooky] and Donald Sosin along with Timothy Brock (and the San Francisco Silent Movie Orchestra), Matti Bye (and ensemble) and Sasha Jacobsen (and quintet) as well as the Anvil Orchestra, Club Foot Hindustani (with Pandit Krishna Bhatt) and the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra. No Benshi this time around, though.

Silents were the original “active cinema” still found in a variety of permutations, from the performative documentaries of Sam Green to the talk-back-to-the-screen “Lost Landscape” screenings of Rick Prelinger. [Is it any wonder that there is a Bay Area connection to both of these spectacular examples? If you accept the notion that Eadweard Muybridge’s motion-studies were proto-cinema, then the Bay Area is the birthplace of the moving image! Granted, if you tend to think of the sequential photographs of the 1874 transit of Venus as the beginning of cinema, nevermind.]

While there are numerous talented folks in front of the screen (and on the screen as well, natch), there are numerous remarkable individuals behind the scenes that make this ambitious event worthwhile. Admittedly, there is a specific trio who take this gathering to another level entirely: SFSFF staffers Anita Monga and Stacey Wisnia and Board member Rob Byrne (fundamental in the organization’s film-restoration efforts as well). To note their specific roles in additional detail would fail to fully describe how their extraordinary activities make this event annually unmissable.

Their collective work and the contributions of everyone involved in the event makes every program on the schedule entirely worth your time. The possibility of recommending merely one or two is rather insufficient. Unlike every other film festival in the world, everything that happens at SFSFF is truly one-of-a-kind; any other screening(s) of the same film(s) would never be quite the same.

If you cannot see it all (although you certainly should if you could carve-out the time), here are a few potential avenues of attack. Definitely try to make the inevitably fascinating Amazing Tales from the Archives, this time a twofer: at the Roxie, May 5 in the afternoon, and the Castro, May 6 in the morning. The latter is free! You should probably make a point to attend the Great Victorian Moving Picture Show as well (with materials from the British Film Institute) since the likelihood of catching any of that again is rather unlikely.

If nothing else, absolutely tackle the formerly-Soviet block: Heorhii Tasin’s essential Arrest Warrant [Order Na Aresht] (1926) from Soviet Ukraine, the legendary Dziga Vertov’s The History of the Civil War [Istoriya Grzhdanskoi Voiny] (1921) from Soviet Russia and the wonderful Mikhail Kalatozov’s Salt for Svanetia [Jim Shvante] (1930) paired with Aleqsandre Jaliashvili’s short Ten Minutes in the Morning (1930), both from Soviet Georgia. My own peculiar ancestral bias would have me highly recommend a journey to Scandinavia (and beyond) with Holger-Madsen’s A Trip to Mars [Himmelskibet] (1918) from Denmark and, Sweden-wise, Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius’ A Sister of Six [Flickorna Gyurkovics] (1926).

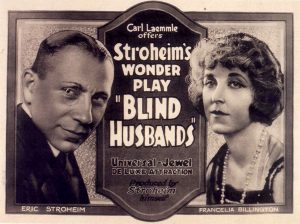

Of course, you could and perhaps should do a double-shot of Austrian-expat Erich von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands (1919) and Foolish Wives (1922), a wonderful husbands-and-wives duo, although you should eventually seek-out (if you haven’t already) his stunning Greed, made the same year—1924—as Edouard-Emile Violet’s The King of the Circus [Max, der Zirkuskönig] and Paul Leni (yet another actor-turned-director) + Leo Birinski’s absolutely extraordinary omnibus Waxworks [Das Waschsfigurenkabinett], where a wax museum serves as a catalyst for the retelling of historical crimes. Or how about the German-expat and fabulously multi-talented Ernst Lubitsch’s Oscar Wilde adaptation, Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925)? A silent play? Indeed, as is the other Wilde-side, Salomé (1922) directed by Alla Nazimova (who also stars as the titular character) and Charles Bryant.

Before I move along, Foolish Wives—the opening night entry with a score composed by the aforementioned Timothy Brock (a detail which, alone, is enough reason to attend)—will be preceded by the short San Francisco: The Golden Gate City, jaw-droppingly rewarding across its mere four minutes. An apt beginning.

Characteristically, I digress.

You couldn’t go wrong with the two French films on the schedule: Charles Vanel’s Dans la nuit (1930) and Julien Duvivier’s The Divine Voyage [La divine croisiére] (1929). I would otherwise tend to seek-out the India, Japanese and Brazilian films myself: Franz Osten and Himansu Rai’s Prem Sanyas (1926), Apart from You [Kimi to Wakarete] (1933) by Mikio Naruse and Mário Peixoto’s Limite (1931), respectively.

As you might wager, the lion’s share of the selections are from the U.S. and a number of those are comparatively well-known: Rebirth of a Nation (1915 / 2022 in this iteration) directed in its initial incarnation by D.W. Griffith (from the racist revisionist-history second-of-a-trilogy novel The Clansman) and remixed visually and musically by DJ Spooky [aka Paul Miller, cinephile and all-around swell fellow], Buster Keaton + Charles Reisner’s fantastic Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928) and one of the other novel-to-film efforts, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) by Wallace Worsley (with Lon Chaney as Quasimodo). If, like me, you’ve seen all three on multiple occasions, perhaps instead you should seek-out the pleasures of The Primrose Path (1925) by Harry Hoyt (best-known for his The Lost World from the same year); Irvin Willat’s Below the Surface (1920), director of an earlier SFSFF restoration project, Behind the Door (1919); the prolific and reliable Clarence Brown’s rom-dram Smouldering Fires (1925); or the considerably grand Herbert Brenon’s The Street of Forgotten Men (1925), featuring the screen-debut of the luminous Louise Brooks. Granted, you could instead simply stick to the three Williams: William Nigh’s The Fire Brigade (1926), William Seiter’s Skinner’s Dress Suit (1926), and/or Penrod and Sam (1923) by William Beaudine, a filmmaker of remarkable range who also directed a pair of 1966 classics: Billy the Kid versus Dracula and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter.

Difficult to choose, right? Might as well see them all.

— Jonathan Marlow [@aliasMarlow]

various (1897-1933) dir. various [various min.]

*[…except for that one occasion when I attended a presentation of F.W. Murnau’s City Girl at MoMA in New York and it unspooled in absolute silence; perhaps they’d mistakenly presumed it was the long-missing soundtrack-added version.]

Pingback: San Francisco Silent Film Festival 2022 | Current - Bokeh