ON THE FRINGE, PART FIVE: PERMANENT VACATION (1980)

One of the many hurdles over which I’ve needed to continuously hop in my “On the Fringe” series is the urgency to come up with synonyms and, ultimately, euphemisms for the descriptor “deceptively simple” in the proper encapsulation of films discussed. It’s something that each movie comprising my list has in common – their all being deceptively simple at first (or, for some viewers/critics, third or fifth) glance.

One of the many hurdles over which I’ve needed to continuously hop in my “On the Fringe” series is the urgency to come up with synonyms and, ultimately, euphemisms for the descriptor “deceptively simple” in the proper encapsulation of films discussed. It’s something that each movie comprising my list has in common – their all being deceptively simple at first (or, for some viewers/critics, third or fifth) glance.

So too could these cinematic works be referred to as “deceptively complex.” Many of the pictures in this series have been at one time or another called “difficult” or “challenging.” They’re certainly…“not for everyone.”

For the most part, these critical analyses are not meant as pejoratives. But, whether intended as derogatory or not, such pronouncements might enable a sense of high-brow elitism as regards consideration of these films, as though they may be watched only for intellectual stimulation, as opposed to intellectual stimulation and basic entertainment.

This goes back to a constant discussion I’ve had with friends, family members and other filmmakers/fans/critics who typically roll their eyes as I rail against folks like Michael Bay emboldening the notion – quite directly in some of his interviews – that there are movies meant as entertainment and there are films meant for illumination.

As though filmmakers (and filmgoers) shouldn’t aspire toward films that can be, you know … both.

Off the top of my head, I’m thinking here of some of the best works of James Cameron (The Terminator, T2: Judgment Day, The Abyss or Aliens, to name a small few) or Paul Verhoeven (particularly his RoboCop, which might be the most salient example of my thesis: it’s got tits, ass, blood, guts, conventional comic book movie tropes before there were such things … and yet it also tells a deep story about the “soul,” the “self,” memory and what it is to be “human”; I actually once had a class taught by its co-writer Michael Miner who revealed he was reading heavy philosophy the entire time he worked on the screenplay).

Yes, movies can be a whole lot of fun and thoughtful/well-crafted. They can be, as another professor at my film school once suggested, “popcorn and caviar.”

Which is how I’d like to think of several works in indie film maven Jim Jarmusch’s deservedly celebrated canon.

His films are often quite fun, quirky, laugh-inducing and emotionally resonant (read: digestible for most audience members). They’re concurrently as often thoughtful and uniquely sincere in their perspectives on various persons, concepts (sometimes quite didactic, as with the case of the life and works of Tesla, which comes up in a few of his flicks) and underrepresented corners of society (even when they so frequently take place in or around his typical digs of hip/underground New York City).

And, of course, they have the added “popcorn”-y bonus of always having killer soundtracks.

Yes, Jarmusch’s films have that very special quality of being inherently watchable by those who want to be mentally uplifted and by those who, frankly, just want to have a good time at the movies. Jarmusch films can also be incisive capsules of their particular time and place, particularly in reference to Stranger Than Paradise, Night on Earth, Down by Law, Coffee and Cigarettes and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, which – along with Broken Flowers – so brilliantly showcases the maestro’s ability to create more mainstream and commercial fare without neglecting his idiosyncratic style and voice we’ve come to expect from “a Jim Jarmusch film.”

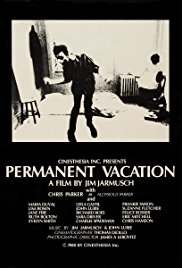

Jarmusch’s debut feature, 1980’s Permanent Vacation, meanwhile, could certainly be called one of his more “challenging” machinations. One could suggest that it is, without a doubt, both “deceptively simple” and “deceptively complex.” The trailer, first few minutes and basic premise might potentially frighten off the most avid Broken Flowers fan.

And yet…Permanent Vacation isn’t really all that complex.

That is, it might scare off a generic viewer perhaps presumptively feeling alienated by the picture’s colder, spartan quality, its macabre sense of loneliness, and interminability and unconscious evocation of dread that comes with the sense of an ultimate void.

As with the more personal works of Jarmusch’s, though, for those willing to take the slow walk with his characters – say, The Limits of Control – Permanent Vacation is well worth the trek; even when the journey leads to nowhere, which it so often does (appropriately so) in a number of Jarmusch’s films.

Films in Jarmusch’s always-growing arsenal such as Permanent Vacation are opt-in experiences. Meaning, once you decide to give in and explore where the movie takes you, it’s merely a matter of just putting one’s shoulders back and permitting it all to blissfully unfold there onscreen.

One of the simple things about Jarmusch’s films is the fact that one need only to opt-in for this singular, authentic experience, with all its contradictions, vivacity and languid monotony mashed in there at once.

And besides, observing the film’s wholly watchable, endearingly hyperkinetic and refreshingly impulsive protagonist with the puckish name of Aloysius “Allie” Christopher Parker (played by the actual inspiration for the film himself, Chris Parker) can be tons-o-fun.

Whether he’s reading a book of poetry he quickly gets bored with to his girlfriend-of-the-moment in their dilapidated, near-empty late seventies NYC loft; swiftly stealing a car from some stuffy urbanite right in front of her own unbelieving eyes or – as is the case with most of the hypnotically Alice in Wonderland-esque picaresque format of the film – wandering beatifically through the broken-down, crumbled city and encountering various odd ducks with their own peculiar askew perspectives to express (sometimes in mumbles, sometimes in song, sometimes in raving shrieks) along the way, Permanent Vacation, on its barebones budget of $12,000 and originally shot on stark, grainy, funereal 16mm film, has far more going on for any film viewer aside from its “simple” logline.

Which, if you were explaining the film to a friend who might not be as familiar with, say, Don Quixote or the actual books detailing Alice’s adventures in Wonderland, or the particular time/place/sensibility of the equally destitute and wondrously unfettered enclave of late seventies downtown New York City, you could, I guess, say this: “It’s a film about a young, squirrely ne’er-do-well walking around the scorched crust of seemingly post-apocalyptic downtown NYC in 1979.”

As best laid out in Celine Danhier’s 2010 documentary Blank City (with some additional contextual material in Jack Sargeant’s brief but encyclopedic 1995 book Deathtripping: The Cinema of Transgression), Jarmusch and his contemporaries at the time were part of a scene that in some ways was more of a loose art collective called No Wave that was spawned from a lot of what was going on in the incipient New York punk cabal and would have a great deal of crossover with the musicians of the same community such as Sonic Youth and Lydia Lynch.

They were far less extreme than their pseudo-compatriots in the Cinema of Transgression crew (Nick Zedd, Richard Kern, Kembra Pfahler, David Wojnarowicz, et al). But both No Wave and Cinema of Transgression filmmakers were in essence trying to achieve the same thing: the telling of new kinds of stories in new kinds of ways with almost no money/resources, and typically involving the truest perspectives – even if often drifting into impressionistic subjectivity – of their own, new world they were all creating together in grimy downtown New York City.

It was at times very cold and boring and monotonous and gray and moribund in that place and time. It could be extremely dark and dangerous. Outsiders only need to brave a quick look at John Holmstrom’s Punk Magazine – more or less the Village Voice of this scene and basically the newsletter of late seventies CBGB’s.

Cartoons (often by Holmstrom himself) throughout each issue reverently lampoon its own community … and unnervingly incorporate so many dead bodies strewn across the sidewalks in their backgrounds (usually with knives stuck in their stomach or back) that one has to wonder how much death was actually going on in that area where these kids were scurrying around making weird no-budget films, playing loud distorted music and trying to figure out how not to freeze or starve in the interim.

Downtown New York City in the late seventies was itself a very opt-in environment where one would either go for it – as is the case with the watching of Permanent Vacation – or else decide to just go back home.

“NYC circa late 70s was a bit like going down the rabbit hole with our different laws (or no law) and different society than the rest of America,” was how one of Jarmusch’s particular contemporaries – his companion, fellow filmmaker and sometimes producer of his films Sara Driver – put it in a brief email conversation I shared with her about a week ago.

Driver, who met Jarmusch at NYU along with a few other notable filmmakers who would pop up in coming years (read: Spike Lee), has a small part in Permanent Vacation as a nurse at the institution that houses Parker’s mentally-ill mother he visits in a sequence that brusquely shrugs its shoulders at any kind of prototypical studio sentimentality.

Driver also helped Jarmusch to make the proto-DIY picture and would go on to produce his next, the Cannes award-winning Stranger Than Paradise (featuring some of the same actors and environs of its modest predecessor of four years).

In speaking of the major component of the film that has that slightly twisted, meditative quality of Alice in Wonderland, Driver noted that “no one had cars back then, so a lot of movies were made of people walking around.”

Driver has in fact been considering an exhibition of movies that specifically focus on people walking around. I suggested she check out Alex Cox’s Three Businessmen. (Readers of this series intrigued by such a concept should stay tuned for my installment about Wendy & Lucy coming soon …)

One of the many films – shorts and features alike – that also had a lot of walking around in it was Edo Bertoglio’s Downtown 81, which took place in the same milieu (culturally and physically) of Permanent Vacation, was shot around the same period and would not see a wide release for nearly two decades.

That film has so many similarities in tone, content and sensibility to Permanent Vacation that I asked Driver outright if she felt the filmmakers behind Downtown 81 had been tipped off by Permanent Vacation to how to put together their ostensibly selfsame production.

“I’m sure [Downtown 81 producer/writer] Glenn [O’Brien] and Edo saw Permanent Vacation,” Driver wrote. “It was shown at Bleecker St Cinema in 1980 … It is wonderful both films exist. What great visual historic records of our burned out destroyed city.”

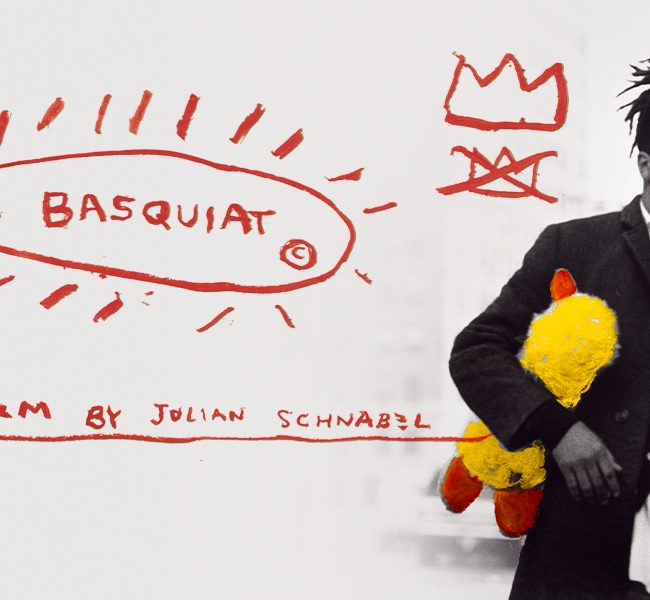

Whereas Permanent Vacation grants the viewer a semi-biographical character study of Chris Parker, Downtown 81 tells its own tale of another upstart free spirit at the time who would blast the entire scene apart with spellbindingly effulgent and whimsically messy paintings: Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Because of the clear affinity between the two pictures, I asked Driver if Jarmusch had always intended to focus on his specific subject, or if Parker was merely one of a handful of scenesters who personified the community (like their friend Basquiat) that the director had been considering canonizing on celluloid.

“I have no idea if Jim was thinking of others,” Driver wrote, adding, “I doubt it. Jim throughout his career writes his scripts for specific people/ actors. Permanent Vacation was written for Chris Parker.”

As with Basquiat and similar wandering sages in the scene at the time (fellow street artist Richard Hambleton, for instance), Parker had something of a reputation as being a very special, genuine article who lived as he lived and did whatever he was going to do.

It was in fact rather hard to track him down for shooting sometimes, and – as with the real-life inspiration for and protagonist of the first film in this series, On The Bowery – after Permanent Vacation came out and especially lit up audiences in Germany, Parker turned away from what might have been an illustrious acting career in large part due to his actually being this fancy-free, frenetic, Neal Cassady-esque character who couldn’t be pinned down as established in the film that tells (more or less) his youthful story.

Meanwhile, Driver has her own interest in Basquiat as a subject: her first film in 25 years is the soon-to-be-released documentary Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

“[Basquiat] was 18 in the summer of 79 [during production of Permanent Vacation],” Driver wrote in an email to me. “Everyone downtown knew him and saw him around on the streets and at clubs.”

“There was a rumor of him being [enigmatic street artist] Samo – there was a mystery around Samo – who was Samo? Who was creating these mysterious poetic writings on the streets? Samo was Jean and Al Diaz…Although Jean claimed it for himself later on.

“Al told me a story that Jean appeared at his apartment a year or two before he died holding a large painting – a triptych – [and] on it was written ‘from Samo to Samo.’ While shooting Permanent Vacation, Jean was sleeping on the floor of [actor, musician and star of Stranger Than Paradise] John Lurie’s apartment.

“He was kind of like the dormouse in Alice and Wonderland. We politely and gently would wake him and tell him we were moving him out of the way of a shot. He would wake up for a moment and then go back to sleep. We would then drag him in the sleeping bag to another corner of the apartment.”

This is a most apt microcosm of the world in which Permanent Vacation’s “Allie” dances around empty, dank and dirty 10-story high loft apartments or meanders diffidently down broken-down streets, talking to fellow transients and popping into porny-looking movie theaters to sit down with rambling, joke-telling bums camping out in the lobby away from the frigid void back outside.

It is the very true, very raw, very brutal but so often very “we-can-do-anything-we-want” attitude of Permanent Vacation that links it so directly with other likeminded pictures of the era that spotlight other parts of underground NYC.

Consider the place and time described in Charlie Ahearn’s and Jim Frickle’s Yes Yes Y’All, an oral history of first-gen hip-hop. Or 1983’s Wild Style and 1984’s Breakin’, both semi-documentary films as inspired by and telling of the growing graffiti and hip-hop community of the region as Permanent Vacation was by/of punk.

The “fuck it, let’s dance (or mosh)” punk ethos so embodied by Chris Parker and Permanent Vacation was intense enough of a fire that one can track its flare-ups across the country: Jonathan Kaplan’s Over the Edge, Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue and Penelope Spheeris’ Suburbia (featuring actual street kids and punk musicians, including a pre-Red Hot Chili Peppers Flea).

Spheeris, who would go on to make such gleefully commercial fare as Wayne’s World and the big-screen adaptations of The Beverly Hillbillies and The Little Rascals, was also responsible for one of the most essential representations of the underground Los Angeles punk scene: a three-part, twenty-year chronicle called The Decline of Western Civilization.

The wanderlust, punk sensibility of Permanent Vacation would again be seen quite directly in Spheeris’ fellow LA underground scene habitué Allison Anders in her debut feature, 1987’s Border Radio, which featured as its amblin’ protagonist John Doe of X.

Next week, we’ll see what happens in Anders’ sophomore effort, as she takes us to dusty tiny-town New Mexico where there is no wandering around at all, only dreams of escape for some young sisters trying to figure out how to break away from their own harsh reality in 1992’s Gas, Food Lodging.

MATHEW KLICKSTEIN is (for the time being) a Boulder-based writer/filmmaker who recently completed and has been touring his documentary on 80s/90s TV icon Marc Summers, On Your Marc, to be widely-released soon. His next book, Springfield Confidential: Jokes, Secrets, and Outright Lies from a Lifetime Writing for The Simpsons (co-written with lifetime series writer/producer Mike Reiss, foreword by Judd Apatow), will be released through Harper Collins this June. You can keep up with his regular shenanigans at www.MathewKlickstein.com.