Los Angeles Film Festival 2013 — A Preview

(The 2013 Los Angeles Film Festival runs June 13th-23rd. Visit the festival’s official website for more information. FULL DISCLOSURE: Paul Sbrizzi is an associate shorts programmer for L.A.F.F., but he put on his film lover/reviewer cape to write this post.)

Just a few personal favorites from the cornucopia of new work playing at this year’s edition of L.A.’s premiere film festival.

Narratives

Eva Neymann’s House with a Turret is an uncanny vision of WWII era Ukraine in which a young boy struggles to bring his sick mother home to his grandfather. Neymann depicts a society that has no particular sympathy for an eight-year-old boy on his own, and his ability to navigate his world is made believable/remarkable by Dmitriy Kobetskoy’s performance. It’s a dramatic scenario, but Neymann is as much concerned with character, composition and movement as she is with story. She creates a stream of quietly stunning shots that bring to mind the stateliness of Dreyer and the rich human tapestries of Jean Renoir. Aside from the extremely subtle movements of the hand-held camera, the film looks like it could have been made in the 1940s.

Eva Neymann’s House with a Turret is an uncanny vision of WWII era Ukraine in which a young boy struggles to bring his sick mother home to his grandfather. Neymann depicts a society that has no particular sympathy for an eight-year-old boy on his own, and his ability to navigate his world is made believable/remarkable by Dmitriy Kobetskoy’s performance. It’s a dramatic scenario, but Neymann is as much concerned with character, composition and movement as she is with story. She creates a stream of quietly stunning shots that bring to mind the stateliness of Dreyer and the rich human tapestries of Jean Renoir. Aside from the extremely subtle movements of the hand-held camera, the film looks like it could have been made in the 1940s.

The premise of Four Dogs would seem at first to be hopelessly indie-familiar, but in the hands of director Joe Burke the film has a quiet power, allowing story and emotion to grow organically from character. Oliver (co-writer Oliver Cooper), a sweet but unambitious aspiring actor new to L.A., spends his days tending to his aunt’s dogs and hanging around with Dan, an embittered older friend from acting class. “I don’t even feel like I am an actor anymore,” says Dan, “I feel like what I am is I’m a professional gas waster.” But the Hollywood loser scenario is subverted as Oliver, for all his immaturity, is shown to be a kind of little Buddha in the midst of all the driving ambition. Cooper brings a light touch to a character that’s usually played for broad laughs, whether dressing up and playing different characters all by himself in an empty house or exerting a calming influence on highly-strung Dan. When Oliver’s mini-crush on a houseguest gets partially fulfilled, the camera catches the range of conflicting emotions that play on his face in the aftermath. Burke finds a beautifully modulated tone, and the performances are inspired and seamless. In the end it’s refreshing to see Hollywood shown to be no more or less than what you make of it.

The premise of Four Dogs would seem at first to be hopelessly indie-familiar, but in the hands of director Joe Burke the film has a quiet power, allowing story and emotion to grow organically from character. Oliver (co-writer Oliver Cooper), a sweet but unambitious aspiring actor new to L.A., spends his days tending to his aunt’s dogs and hanging around with Dan, an embittered older friend from acting class. “I don’t even feel like I am an actor anymore,” says Dan, “I feel like what I am is I’m a professional gas waster.” But the Hollywood loser scenario is subverted as Oliver, for all his immaturity, is shown to be a kind of little Buddha in the midst of all the driving ambition. Cooper brings a light touch to a character that’s usually played for broad laughs, whether dressing up and playing different characters all by himself in an empty house or exerting a calming influence on highly-strung Dan. When Oliver’s mini-crush on a houseguest gets partially fulfilled, the camera catches the range of conflicting emotions that play on his face in the aftermath. Burke finds a beautifully modulated tone, and the performances are inspired and seamless. In the end it’s refreshing to see Hollywood shown to be no more or less than what you make of it.

Veteran director Johnny To’s Drug War is reminiscent of the stripped-down, muscular action films Warner Brothers made in the noir era—with that modern Hong Kong flava of course, although it’s actually To’s first film to be shot in mainland China. Ming, a druglord, is captured and agrees to turn informant for police captain Zhang, and together they con their way into penetrating the highest ranks of a drug cartel, with Zhang hilariously impersonating the clownish boss they capture in their first sting. To camouflages his impressive auteur chops with genre, placing his rich and complex characters in a series of high-stakes games of strategy within thrillingly layered and choreographed scenes. There’s no CGI, no big explosions, no bone-crunching sound-effects, just good old-fashioned violence, particularly in the gritty, orgiastic, men-made-into-meat finale.

Veteran director Johnny To’s Drug War is reminiscent of the stripped-down, muscular action films Warner Brothers made in the noir era—with that modern Hong Kong flava of course, although it’s actually To’s first film to be shot in mainland China. Ming, a druglord, is captured and agrees to turn informant for police captain Zhang, and together they con their way into penetrating the highest ranks of a drug cartel, with Zhang hilariously impersonating the clownish boss they capture in their first sting. To camouflages his impressive auteur chops with genre, placing his rich and complex characters in a series of high-stakes games of strategy within thrillingly layered and choreographed scenes. There’s no CGI, no big explosions, no bone-crunching sound-effects, just good old-fashioned violence, particularly in the gritty, orgiastic, men-made-into-meat finale.

Released in 1959, Jean-Pierre Melville’s Two Men in Manhattan is a perfect snapshot of polished ‘50s noir starting to open up into the looser and more self-aware approach of the French New Wave. Unusual for Melville, the film has a breathless, shot-on-the-fly immediacy to it; his vision of New York City is halfway between awestruck snapshot and caricature, filled with soaring marquees, illuminated billboards, and enormous, tail-finned cars gliding through the inky night. In an attempt to solve the mystery behind the disappearance of a French diplomat, a pair of French journalists (one of whom is played by Melville, in the only starring role of his career) track down and question a series of vamps. The actresses are uniformly stiff and campy, seemingly cast entirely for their looks, which on a certain level works nicely—another note of dry humor directed at us Yanks.

Released in 1959, Jean-Pierre Melville’s Two Men in Manhattan is a perfect snapshot of polished ‘50s noir starting to open up into the looser and more self-aware approach of the French New Wave. Unusual for Melville, the film has a breathless, shot-on-the-fly immediacy to it; his vision of New York City is halfway between awestruck snapshot and caricature, filled with soaring marquees, illuminated billboards, and enormous, tail-finned cars gliding through the inky night. In an attempt to solve the mystery behind the disappearance of a French diplomat, a pair of French journalists (one of whom is played by Melville, in the only starring role of his career) track down and question a series of vamps. The actresses are uniformly stiff and campy, seemingly cast entirely for their looks, which on a certain level works nicely—another note of dry humor directed at us Yanks.

Janis Nords’ Mother I Love You dives deep into the drives and conflicts of an adolescent boy in Latvia with a single working mother. The consequences of a bit of light mischief escalate to a Von Trier-sized ethical dilemma. Kristofers Konovalovs turns in an exquisitely layered performance as the boy who risks getting banished from his home, away from the mother he adores. The entire production lives and breathes with a naturalism that retains all the sharp edges of life.

Janis Nords’ Mother I Love You dives deep into the drives and conflicts of an adolescent boy in Latvia with a single working mother. The consequences of a bit of light mischief escalate to a Von Trier-sized ethical dilemma. Kristofers Konovalovs turns in an exquisitely layered performance as the boy who risks getting banished from his home, away from the mother he adores. The entire production lives and breathes with a naturalism that retains all the sharp edges of life.

With I’m So Excited, Pedro Almodovar lets his inner dizzy queen out to play in the friendly skies. It’s a nod to old Doris Day movies and MGM musicals, lovingly production-designed in poppy ‘50s pastels and filtered through a mad, hypersexualized ‘70s sensibility. When the two rather gorgeous pilots of a plane bound for Mexico realize their landing gear and in-flight entertainment are shot, a trio of deliciously fruity flight attendants must attempt to keep the passengers distracted while preparations for a crash-landing are made. All kinds of back-story intrigue bubbles to the surface—it’s a mile-high-club bedroom farce highlighted by a dazzling lipsynch-and-dance performance of the old Pointer Sisters chestnut. And yet, just beneath the good, frothy summer fun, it’s possible to read a darker implication: the flight attendants as a metaphor for the contemporary filmmaker, creating a trivial diversion as the end of days draws near.

With I’m So Excited, Pedro Almodovar lets his inner dizzy queen out to play in the friendly skies. It’s a nod to old Doris Day movies and MGM musicals, lovingly production-designed in poppy ‘50s pastels and filtered through a mad, hypersexualized ‘70s sensibility. When the two rather gorgeous pilots of a plane bound for Mexico realize their landing gear and in-flight entertainment are shot, a trio of deliciously fruity flight attendants must attempt to keep the passengers distracted while preparations for a crash-landing are made. All kinds of back-story intrigue bubbles to the surface—it’s a mile-high-club bedroom farce highlighted by a dazzling lipsynch-and-dance performance of the old Pointer Sisters chestnut. And yet, just beneath the good, frothy summer fun, it’s possible to read a darker implication: the flight attendants as a metaphor for the contemporary filmmaker, creating a trivial diversion as the end of days draws near.

In Delivery, director Brian Netto uses horror to give the reality genre a good mauling. In the TV-show-within-the-movie, also called “Delivery,” Kyle and Rachel are too too perfect as the adorable couple overcoming mild conflicts on their way to having their first baby. The show’s bland scenario gets subverted from its core as it gradually becomes clear that the baby itself is a demonic force with a lust to kill, and it’s wicked fun to behold.

In Delivery, director Brian Netto uses horror to give the reality genre a good mauling. In the TV-show-within-the-movie, also called “Delivery,” Kyle and Rachel are too too perfect as the adorable couple overcoming mild conflicts on their way to having their first baby. The show’s bland scenario gets subverted from its core as it gradually becomes clear that the baby itself is a demonic force with a lust to kill, and it’s wicked fun to behold.

Documentaries

The don’t-miss film of the festival is the much-talked-about The Act of Killing, a movie that represents a new benchmark in the ongoing trend of using documentary as a medium for storytelling as opposed to verité-style reportage. In an effort to shed light on the mass killings of over a million people in Indonesia in the 1960s in a so-called communist purge, director Joshua Oppenheimer engages actual death squad leaders to direct and perform their own reenactments of the murders. The result is a jaw-dropping trip into a surreal theater of cruelty: clinically dispassionate descriptions of best practices for killing spiral out into candy-coated fantasy worlds of rationalization. Even more interestingly, revisiting the atrocities they committed and for which they were never called to task begins to have an effect on the killers—particularly the central character Anwar. His confused sense of growing remorse plays out before the camera, even as the camera itself is affecting the theatricality of how his emotions are expressed. Read Jesse Klein’s full H2N review here.

The don’t-miss film of the festival is the much-talked-about The Act of Killing, a movie that represents a new benchmark in the ongoing trend of using documentary as a medium for storytelling as opposed to verité-style reportage. In an effort to shed light on the mass killings of over a million people in Indonesia in the 1960s in a so-called communist purge, director Joshua Oppenheimer engages actual death squad leaders to direct and perform their own reenactments of the murders. The result is a jaw-dropping trip into a surreal theater of cruelty: clinically dispassionate descriptions of best practices for killing spiral out into candy-coated fantasy worlds of rationalization. Even more interestingly, revisiting the atrocities they committed and for which they were never called to task begins to have an effect on the killers—particularly the central character Anwar. His confused sense of growing remorse plays out before the camera, even as the camera itself is affecting the theatricality of how his emotions are expressed. Read Jesse Klein’s full H2N review here.

In First Cousin Once Removed, documentarian Alan Berliner continues his exploration of his family history, turning the camera on his father’s cousin Edwin Honig, a renowned poet now living with Alzheimer’s. What would seem like unbearably heavy subject matter is buoyed by Berliner’s clear-eyed but playful approach. Edwin’s mind, despite the memory loss, is a fun and fascinating place: he creates impromptu word games that often spin out into gibberish, then blindsides you with something effortlessly profound. Berliner coaxes out of him reflections on the memory loss itself, and deftly moves into darker material, such as the childhood trauma Edwin still remembers acutely, and his badly damaged relationship with his two sons. But then there’ll be a flash of Edwin’s manic, fun side—like when Berliner asks him what kind of music he likes. His face lights up: “Jazzy!”

In First Cousin Once Removed, documentarian Alan Berliner continues his exploration of his family history, turning the camera on his father’s cousin Edwin Honig, a renowned poet now living with Alzheimer’s. What would seem like unbearably heavy subject matter is buoyed by Berliner’s clear-eyed but playful approach. Edwin’s mind, despite the memory loss, is a fun and fascinating place: he creates impromptu word games that often spin out into gibberish, then blindsides you with something effortlessly profound. Berliner coaxes out of him reflections on the memory loss itself, and deftly moves into darker material, such as the childhood trauma Edwin still remembers acutely, and his badly damaged relationship with his two sons. But then there’ll be a flash of Edwin’s manic, fun side—like when Berliner asks him what kind of music he likes. His face lights up: “Jazzy!”

Easily the most charming, offbeat film of the festival is The Women and the Passenger, in which directors Patricia Correa and Valentina Mac-Pherson listen to the reflections of the maids in a fantasy-theme-room sex motel in Chile as they go about their unhurried task of cleaning up the aftermaths of one-night encounters. These women are cinematic gold: not the least bit bewildered or hardened by the environment they work in, their thoughts flow freely, imagining with a childlike wonder what might have happened the night before, discussing their own sexual and romantic lives with an easy candor, gossiping about the vulgar women that come in with handsome and well-to-do men. You really couldn’t cast a better assortment of characters, each with her own distinct life story and point of view, but sharing a down-to-earthness that contrasts so nicely with the kitschy-surreal environment they work in.

Easily the most charming, offbeat film of the festival is The Women and the Passenger, in which directors Patricia Correa and Valentina Mac-Pherson listen to the reflections of the maids in a fantasy-theme-room sex motel in Chile as they go about their unhurried task of cleaning up the aftermaths of one-night encounters. These women are cinematic gold: not the least bit bewildered or hardened by the environment they work in, their thoughts flow freely, imagining with a childlike wonder what might have happened the night before, discussing their own sexual and romantic lives with an easy candor, gossiping about the vulgar women that come in with handsome and well-to-do men. You really couldn’t cast a better assortment of characters, each with her own distinct life story and point of view, but sharing a down-to-earthness that contrasts so nicely with the kitschy-surreal environment they work in.

The obvious draw of Penny Lane’s Our Nixon is the Super-8 footage shot by the cabinet members, a fascinating reversal of the way we typically look at power or celebrity. What also emerges is a unique coming-of-age story about a group of young men finding themselves in a world where they can write their own rules and anything is possible, and essentially driving too fast and crashing. The Nixon White House tapes are used extensively on the soundtrack and provide a sense of the kind of directives the men were given, and the culture of the place. There’s a surprising degree of naïve earnestness at the core of all the scheming that feels very different from the bitter and fanatical tone of modern right-wing politics. Much like The Iron Lady, Our Nixon stays very much inside the POV of its characters, which could be considered a strong choice in terms of filmmaking, but creates a bit of a conundrum: if you aren’t familiar with the history of the time, Our Nixon might leave you thinking the Nixon administration was a rather benign force, ending the Vietnam war and opening to China, and that the peace movement hippies were the misguided troublemakers.

The obvious draw of Penny Lane’s Our Nixon is the Super-8 footage shot by the cabinet members, a fascinating reversal of the way we typically look at power or celebrity. What also emerges is a unique coming-of-age story about a group of young men finding themselves in a world where they can write their own rules and anything is possible, and essentially driving too fast and crashing. The Nixon White House tapes are used extensively on the soundtrack and provide a sense of the kind of directives the men were given, and the culture of the place. There’s a surprising degree of naïve earnestness at the core of all the scheming that feels very different from the bitter and fanatical tone of modern right-wing politics. Much like The Iron Lady, Our Nixon stays very much inside the POV of its characters, which could be considered a strong choice in terms of filmmaking, but creates a bit of a conundrum: if you aren’t familiar with the history of the time, Our Nixon might leave you thinking the Nixon administration was a rather benign force, ending the Vietnam war and opening to China, and that the peace movement hippies were the misguided troublemakers.

A New York City Balkan Brass Band named Zlatne Uste has been actively performing since the 1980s. Its members are deeply passionate about the traditional music of Serbia despite not being Serbian themselves. Their dream is to travel to Guča, in Serbia, to play at the world’s largest festival of Balkan music. But there’s a huge, lingering resentment amongst Serbians toward the U.S., because of the 1999 bombings during the war in Kosovo. In Brasslands, the Meerkat Media Collective follows Zlatne Uste on their strange dream trip to a country mined with hostility, picking up footage of the amazingly talented (and comically arrogant) reigning king of Balkan trumpet, Dejan Petrović. There’s something quite touching about Americans playing this music for a Serbian audience and to some extent winning them over—it’s not an apology, but it is an implicit statement of soul-level understanding.

A New York City Balkan Brass Band named Zlatne Uste has been actively performing since the 1980s. Its members are deeply passionate about the traditional music of Serbia despite not being Serbian themselves. Their dream is to travel to Guča, in Serbia, to play at the world’s largest festival of Balkan music. But there’s a huge, lingering resentment amongst Serbians toward the U.S., because of the 1999 bombings during the war in Kosovo. In Brasslands, the Meerkat Media Collective follows Zlatne Uste on their strange dream trip to a country mined with hostility, picking up footage of the amazingly talented (and comically arrogant) reigning king of Balkan trumpet, Dejan Petrović. There’s something quite touching about Americans playing this music for a Serbian audience and to some extent winning them over—it’s not an apology, but it is an implicit statement of soul-level understanding.

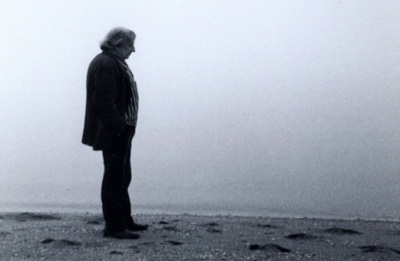

Global warming has taken the place of nuclear holocaust in our collective fear of human extinction, and in Daniel Dencik’s Expedition to the End of the World, a team of scientists plus an artist and a photographer travel to Greenland, a frontline of climate change, to examine and meditate on the ice as it collapses before our eyes. Not everything about the project gels: the interactions between the luminaries tend to fall spectacularly flat, and the theorizing sometimes drifts into the depressingly glib (“so we move to Switzerland” shrugs one of them). The artist’s crayon drawings of nature belie a comically reductive understanding of what art is. But the science itself is consistently disturbing and fascinating—in particular, Geologist Minik Rosing describes a commonly observed process: a species (us, for example) thrives and multiplies in a favorable environment, but as it thrives it causes its environment to change faster than it’s able to adapt. It’s heady, powerful stuff, and rapidly-changing Greenland is the perfect, spectacular backdrop.

Global warming has taken the place of nuclear holocaust in our collective fear of human extinction, and in Daniel Dencik’s Expedition to the End of the World, a team of scientists plus an artist and a photographer travel to Greenland, a frontline of climate change, to examine and meditate on the ice as it collapses before our eyes. Not everything about the project gels: the interactions between the luminaries tend to fall spectacularly flat, and the theorizing sometimes drifts into the depressingly glib (“so we move to Switzerland” shrugs one of them). The artist’s crayon drawings of nature belie a comically reductive understanding of what art is. But the science itself is consistently disturbing and fascinating—in particular, Geologist Minik Rosing describes a commonly observed process: a species (us, for example) thrives and multiplies in a favorable environment, but as it thrives it causes its environment to change faster than it’s able to adapt. It’s heady, powerful stuff, and rapidly-changing Greenland is the perfect, spectacular backdrop.

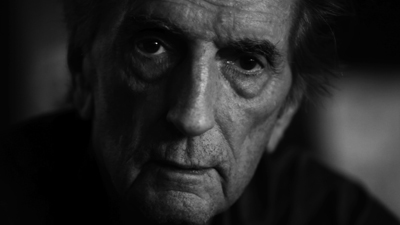

Harry Dean Stanton may be a reticent storyteller, but director Sophie Huber brings out his soulful presence through clips from his films, and most memorably by having him sing a clutch of favorite songs. Throughout Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction, his eyes captivate you—dark pools of pure, raw emotion. His roadmapped face is beautifully captured in chiaroscuro black-and-white. One irresistible highlight is the visit from David Lynch, with an adorably nerdy printout of questions for Stanton in hand.

Harry Dean Stanton may be a reticent storyteller, but director Sophie Huber brings out his soulful presence through clips from his films, and most memorably by having him sing a clutch of favorite songs. Throughout Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction, his eyes captivate you—dark pools of pure, raw emotion. His roadmapped face is beautifully captured in chiaroscuro black-and-white. One irresistible highlight is the visit from David Lynch, with an adorably nerdy printout of questions for Stanton in hand.

In the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution of 1979, there was a horrific crackdown on political dissidents, with countless arrests, torture and executions. People were herded into cramped cells without even enough floor space for everyone to sleep. In My Stolen Revolution, filmmaker/activist Nahid Persson, who was lucky to escape the country just in time but lost her younger brother, tracks down and interviews former comrades who did time in the notorious cells. The stories are pure horror, almost unfathomable, and many of the prisoners were broken beyond repair by their experience. But amazingly a few of them had the strength to endure: even as they speak about their ordeal there’s a lightness and easy confidence about them—their spirits came through unscathed.

In the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution of 1979, there was a horrific crackdown on political dissidents, with countless arrests, torture and executions. People were herded into cramped cells without even enough floor space for everyone to sleep. In My Stolen Revolution, filmmaker/activist Nahid Persson, who was lucky to escape the country just in time but lost her younger brother, tracks down and interviews former comrades who did time in the notorious cells. The stories are pure horror, almost unfathomable, and many of the prisoners were broken beyond repair by their experience. But amazingly a few of them had the strength to endure: even as they speak about their ordeal there’s a lightness and easy confidence about them—their spirits came through unscathed.

In Purgatorio, director Rodrigo Reyes takes a bold new look at the U.S./Mexico border, setting aside political and public policy considerations and putting the physical presence of the actual fence front and center. Through evocative cinematography and conversations with the people that directly affect and are affected by it, including a fascinating scene with a Minuteman, he takes a long view of the border as a kind of mythical place of suffering at a particular time in history.

In Purgatorio, director Rodrigo Reyes takes a bold new look at the U.S./Mexico border, setting aside political and public policy considerations and putting the physical presence of the actual fence front and center. Through evocative cinematography and conversations with the people that directly affect and are affected by it, including a fascinating scene with a Minuteman, he takes a long view of the border as a kind of mythical place of suffering at a particular time in history.

An actual emergency room doctor himself, director Ryan McGarry examines in Code Black the drives and motivations of young ER doctors, with raw and compelling footage of how the business of saving lives is handled at L.A. County General Hospital. He documents the cramped and chaotic madness of the old ER—a storied place that pioneered a modern approach to treating medical emergencies half a century ago. In recent years, because they worked under precarious conditions, doctors were given a lot of leeway to use all means necessary to help their patients. Code Black highlights how drastically things changed when a new building was completed, showing the stark contrast between the old ER and the brand-new facilities where bureaucracy suffocates the doctors’ passion for their work.

An actual emergency room doctor himself, director Ryan McGarry examines in Code Black the drives and motivations of young ER doctors, with raw and compelling footage of how the business of saving lives is handled at L.A. County General Hospital. He documents the cramped and chaotic madness of the old ER—a storied place that pioneered a modern approach to treating medical emergencies half a century ago. In recent years, because they worked under precarious conditions, doctors were given a lot of leeway to use all means necessary to help their patients. Code Black highlights how drastically things changed when a new building was completed, showing the stark contrast between the old ER and the brand-new facilities where bureaucracy suffocates the doctors’ passion for their work.

In Rain, Olivia Rochette and Gerard-Jan Claes take a wonderfully impressionistic approach to documenting the extensive preparations for a modern dance performance at the Opéra de Paris. It’s a dreamy scrapbook of visual details, voice mails, fleeting dramas, and snatches of conversation filled with both doubts and excitement, artfully conveying the colorful and gritty swirl of energies that converge behind the scenes.

In Rain, Olivia Rochette and Gerard-Jan Claes take a wonderfully impressionistic approach to documenting the extensive preparations for a modern dance performance at the Opéra de Paris. It’s a dreamy scrapbook of visual details, voice mails, fleeting dramas, and snatches of conversation filled with both doubts and excitement, artfully conveying the colorful and gritty swirl of energies that converge behind the scenes.

In addition to the Edwin Honig and Harry Dean Stanton docs, LAFilmFest is screening a whole range of great film biographies. Casting By brings to light the crucial role casting played in the making of the seminal films of the late ‘60s and ‘70s and beyond, courtesy of the great and underappreciated casting agent Marion Dougherty. The Crash Reel documents the aftermath of the horrific traumatic brain injury suffered by Kevin Pearce, one of the greatest snowboarders of all time, and his determination to recover and make sense of his life. Our Vinyl Weighs a Ton profiles Chris Manak, AKA Peanut Butter Wolf, who has bravely and successfully charted his own course with his Stones Throw Records, the independent label he founded in 1996 after his partner in a hip-hop group was murdered. The Moo Man follows a disarmingly gentle and patient English dairy farmer and his unique, caring relationship with his animals. Tapia is the touching story of the New Mexico boxing champion’s roller coaster of success, fame, imprisonment and cocaine addiction, as he fights personal demons related to the brutal murder of his mother when he was a child.

Shorts

Animation highlights include Javier Barbosa’s dark and dreamy Papel Picado, about a man falling through the floors of a building in the aftermath of a break-up. It’s painstakingly created by shooting a series of hand-made, cut-out figures in a three-dimensional space. Drifters by Ethan Clarke is like the greatest thing you’ve never seen on Adult Swim, a brilliant step forward in acid-trip character-based animation, the kind of comedy that gets darker the deeper you look into it. In The Bungled Child, Simon Fillot crafts gorgeously crude characters and pits them against each other in violent games of control, in which they get sliced open and apart and sewn back together and even have XXX puppet sex.

Narratives include Jenni Toivoniemi’s The Date, in which a shy and awkward teenage boy plays host to a brassy middle-aged woman and her daughter as their thoroughbred cats have a horrifically loud breeding session. Quvenzhané Wallis stars in Frances Bodomo’s raw and lyrical Boneshaker as a young girl prone to screaming tantrums. Her parents take her to a revival tent in an attempt to have her healed by the fire of God. In Dejà Vu, Jean-Guillaume Bastien creates a stark visual poem, shooting a series of five women in sort of depressive-Toni-Basil individual worlds of abstraction, then bringing them together in an affecting, minimal choreography. F to 7th – Interchangeable is Ingrid Jungermann’s sharply observed and wonderfully deadpan comedy about a lesbian with old-fashioned scruples trying to handle an internet date with an insanely overconfident and condescending partner. Ben Rycroft’s A Modern Man dramatizes the conflict between a South African businessman and his sensitive and vulnerable brother who always manages to end up in trouble. They’re emblematic of a wider cultural divide, but Rycroft builds his discourse around two vivid and lovingly crafted characters and a relationship that’s specific and resonant. Kahlil Joseph’s Until the Quiet Comes is a thing of frightening beauty, a wordless meditation on death and life featuring a seriously spooky dance to a Flying Lotus track, shot in L.A.’s violent, crime-ridden Nickerson Gardens housing project.

— Paul Sbrizzi