RAY LOBO AND JONATHAN MARLOW TACKLE BREATHLESS

Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (which has a fantastic 4k restoration, plays September 24-October 7 at NYC’s Film Forum) has been analyzed by critics, directors, writers, academics, and cinephiles across the world. Hammer to Nail contributors Jonathan Marlow and Ray Lobo share a love for world cinema. We here at Hammer to Nail thought Breathless was deserving of two reviewers; and instead of having Jonathan and Ray battle over who got to review Breathless, we thought of offering them both a chance to share their perspectives on the film. The comments below offer perspectives that both cohere and differ, as is expected when discussing a master such as Godard.

Ray Lobo

A restoration and theatrical re-release of Godard’s Breathless and the expectations are there, hovering above me as I write this. I am expected at some point to mention how innovative Breathless was, its enormous influence, and its timelessness. I should make mention of all this, but I will not. The film’s legacy has been mapped out by many writers in many ways. I will not tread the same territory. That does not mean I will tread on a completely alien terrain. Great works of art — be they literary, musical, or pictorial — are fecund. They generously offer their audience a bounty of interpretations, sub-textual readings, and feelings. It may be a trite but nonetheless true remark that great works of art reveal themselves to us in different ways based at what age we experience them. This, at the age of 44, being my third viewing of Breathless; Godard’s masterpiece rewarded me with renewed exhilaration. It revealed itself to me in a new way. Even though I felt new sensations, it was all too expected with Breathless. That is what great art does.

Jonathan Marlow

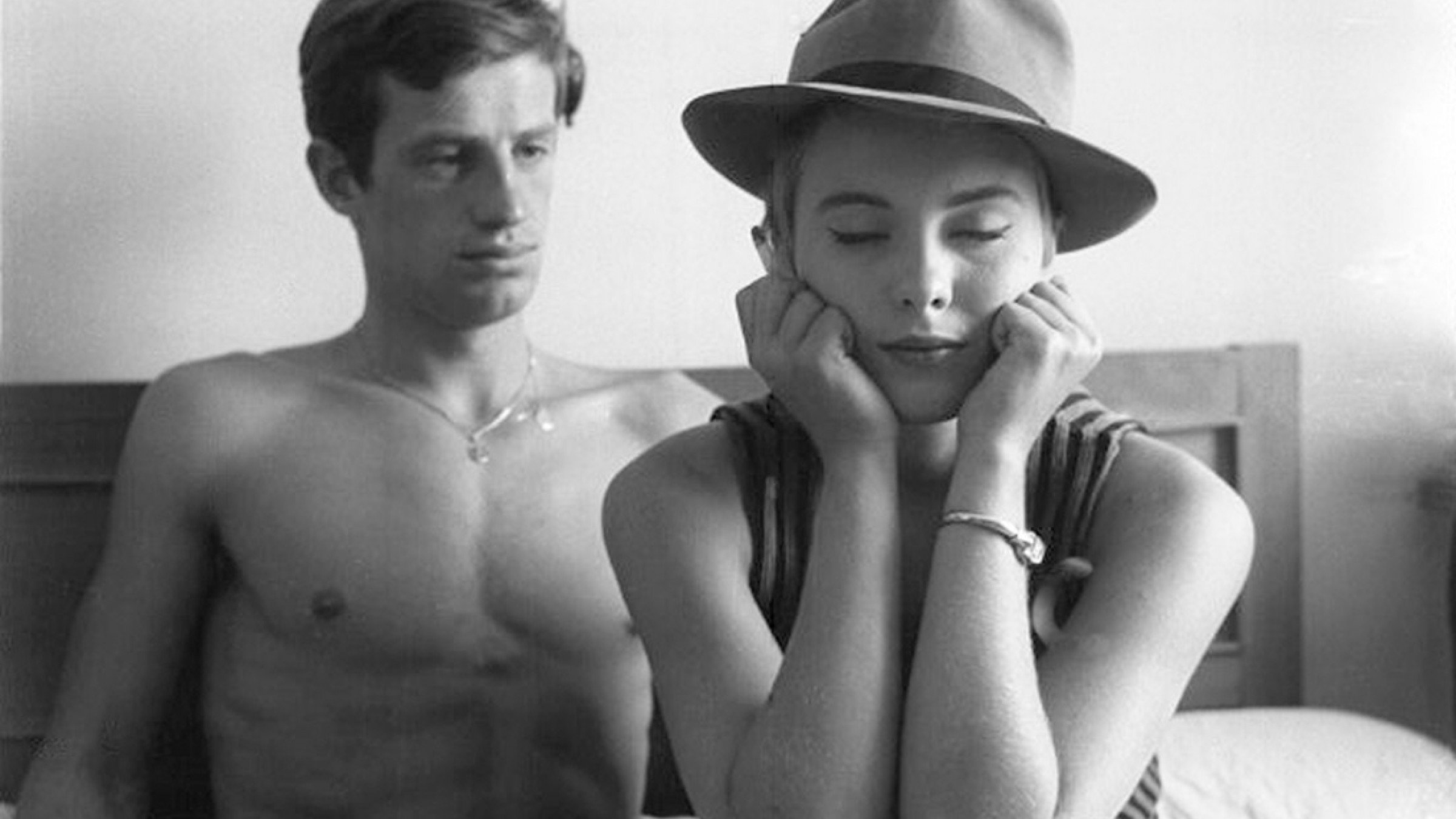

I am sitting in a room. The room could be anywhere but it happens to be in Phoenix, Arizona. It is here in this room that I immerse myself in a delirious repeat-viewing — for the fifth time, I wager — of Breathless. It is claimed to be the first film of the nouvelle vague. It was not (a distinction seemingly deserved of Agnès Varda or, alternatively, Claude Chabrol (who subsequently developed the Breathless scenario with François Truffaut). It is sometimes claimed to be the first screen-appearance of its star, the wonderful Jean-Paul Belmondo. It isn’t (and it wasn’t even his first time acting for the writer/director, Jean-Luc Godard; he appeared in an earlier short film [and if you haven’t seen Godard’s shorts, you definitely should]). It is even claimed to represent the beginnings of the jump-cut (a notion which seems to conveniently forget the entire silent-era of Soviet montage). Too much is made of firsts, regardless. The film is revolutionary in its bringing-together of all of these elements and others, particularly in its use and abuse of abrupt audio-cues, a technique that Godard has used to masterful effect ever-after.

Ray Lobo

What revealed itself this time around is how kinetic Breathless feels. The stereotype with foreign arthouse movies is that they are ponderous. That is not the case with Breathless. It moves at breakneck speed. It feels shorter than its 90-minute runtime. Breathless is the cinematic equivalent of Kerouac’s On the Road. Michel Poiccard (played by the recently deceased Jean-Paul Belmondo) is a cyclone of activity. Michel is a smalltime crook that is all go go go. If he is not tracking down people who owe him money, then he is literally sprinting down Parisian streets; and when he is not a flash of movement on two legs, he is a speeding streak behind the wheel of a car. He declares his manifesto early on: “Never brake. Cars are made to go, not stop.” Michel is obsessed with the idea of escape. He wants to go to Rome and spends virtually the entire film pursuing and attempting to convince his American love interest, Patricia (Jean Seberg), to abandon her studies at the Sorbonne and join his accelerated life. Stagnation is his enemy. Patricia’s hesitance to join him irritates him. Slow drivers, road work, and traffic are clots that block his flow of life. And that is the thing with Breathless, it moves at Michel’s hyper-speed of life. The blood that pumps and rushes through Michel’s body seems to flow on through to the city of Paris. No city has felt more alive than Paris feels in Breathless.

Jonathan Marlow

The opening-credits dedication is to Monogram Pictures, a studio primarily known for their relatively inexpensive genre films of the 1930s, ‘40s and early-‘50s, substantially crime films and westerns. Monogram was originally the distributor-of-choice for Joseph Lewis’ Gun Crazy, the spiritual step-sister of Breathless a decade earlier. Although never mentioned anywhere in the film, Breathless could additionally open with, “Based on a true story.” Michael Poiccard (in reality, Michel Portail) had a journalist lady-friend visiting from the U.S. He stole an automobile and ultimately — spoiler, natch — killed a motorcycle police officer (precisely as occurs in the initial moments of the film). Michael / Michel was on-the-run thereafter but the similarities seemingly end there. Chabrol and Truffaut weren’t the only cinema-folks associated with the film. Jacques Rivette appears as the pedestrian-victim of an automobile accident; Jean-Pierre Melville has a minor role as well (and if you have any familiarity with him in his own Two Men in Manhattan or any of his other occasional acting appearances, his visage in Breathless never ceases to be a quaint and all-too-brief surprise). What we have here is a France-by-way-of-U.S. or U.S.-by-way-of-France attitude that runs throughout the entire picture. It takes the sensations of Martial Solal’s jazz score and distills it through the images on the screen. Or the other-way-around.

Ray Lobo

Speaking of driving and Paris, is there a more beautiful and mesmerizing shot than the one Godard gives us of the back of Patricia’s neck as she is driven around the streets of Paris in Michel’s convertible? On the face of things, sure, Patricia lives at a slower speed than Michel — she is driven, she is Michel’s passenger. She is pregnant and is understandably hesitant to go to Rome with a scoundrel who has trouble written all over him. But Patricia also possesses a vitality, a life force gathering speed toward some future direction. She is young, beautiful, her career is starting to take shape, and has many possibilities ahead of her.

Jonathan Marlow

For all of the talk of Bogart-by-way-of-Belmondo — and, admittedly, he is terrific — the real gem of the cast is truly Jean Seberg. The film becomes something-else-altogether each time she is on the screen. It is difficult to effectively recall at this point the persistent pans of her debut in Saint Joan. Iowa-born, how did she find herself in Paris? It was on the set of her second film — Bonjour Tristesse — when she met her first husband. She settled in France for work and for a short-lived romance. Her fourth screen appearance in Breathless justifiably made her an international star. Arguably, despite a decade-and-a-half of great performances — and numerous misses (largely due to weak material, a mismatched director or both) — thereafter, she was never bette…although Philippe Garrel’s casting of her and Nico together in Les hautes solitudes is an unusually close second if you go for that sort of thing; some folks have a soft-spot for her role in Paint Your Wagon, too, but I am not among them. For an exceptional portrait of this remarkable actor, you can do no better than Mark Rappaport’s extraordinary From the Journals of Jean Seberg (featuring Mary Beth Hurt; once upon a time, Seberg had been her babysitter).

Ray Lobo

Godard creates this feeling of acceleration, of life flow, through his jump edits. But this is not his only trick. Even the section involving the long dialogue between Michel and Patricia in her flat does not feel like a tedious palate cleansing interval. The dialogue is snappy. And even as Michel and Patricia share intimacies with each other, their voices are occasionally drowned out by the wails of ambulances and cop cars rushing along outside the flat’s window. The indication is clear: the outside world continues its flow independent of Michel and Patricia. Breathless feels like an electrical livewire. But even that observation is too one-dimensional on my part. Godard juxtaposes every thematic of life, vitality, and movement, with a sensation of stagnation, death, and nothingness.

Michel fears the stagnation of prison. Patricia perhaps realizes that going to Rome with Michel will lead to her stagnation, her erasure, her nothingness. Is this realization the reason why she decides to turn Michel over to the cops? Does Michel represent for Patricia a face-to-face confrontation with nothingness, with a closed future? Perhaps. Perhaps not. Perhaps another viewing of Breathless, ten years from today, may offer a more definitive answer based on something I may have overlooked this time around. Or who knows, perhaps an entirely novel interpretation may reveal itself. Breathless is an everlasting fruit-bearing tree of interpretations.

Jonathan Marlow

Is Breathless Godard’s best film? Definitely not. Is it his first film? Alas, no (although it is his first feature-length). Is there anyone else still making fascinating and challenging work sixty(!) years after their debut? If so, name them.

JLG will be JLG, from the beginning to the end. Breathless, ultimately, is a film about filmmaking. One could claim that this is true of all of his films (as well as each being about something else, too). The process is laid bare. Literature, for some, arrived there ages earlier, as had many of the other arts. Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti’s Vanessa, anyone? Everyone? As a ‘maker, Godard wants to draw attention to all of the things that “proper filmmaking” is supposed to disguise. What does the viewer gain when attention is drawn to those elements which would otherwise be hidden? Everything. Everything and nothing, depending on the disposition of the audience.

– Ray Lobo (@RayLobo13) and Jonathan Marlow (@aliasMarlow)