Edison’s School of Filmcraft and Wizardry

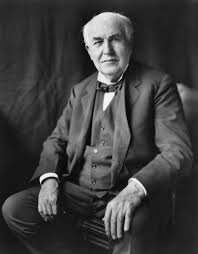

Most people have at least heard the name of Thomas Edison (that’s Thomas Alva Edison), even if they don’t know anything about the man. Light bulbs, anyone? Well, he invented them. OK, maybe that’s about as true as saying that Steve Jobs invented the personal computer (he didn’t), but like Jobs, Edison’s particular strength was bringing together extraordinarily talented engineers and working with them to produce products that the general public might actually enjoy using. Hence, the reason we associate Edison with the light bulb is because he produced the first commercially viable version.

Edison’s technological innovations didn’t stop there: he also developed the phonograph, other audio recording and playing machines, and the first American motion-picture camera (working with inventor W.K.L. Dickson). Even before he created the device that would define 20th-century mass culture, Edison had earned the nickname “The Wizard of Menlo Park” (Menlo Park was a development in New Jersey where he housed his factories until 1887) for his ability to seemingly bring magic into the world. Brilliant, charming and energetic, Edison was a renaissance entrepreneur.

Edison’s technological innovations didn’t stop there: he also developed the phonograph, other audio recording and playing machines, and the first American motion-picture camera (working with inventor W.K.L. Dickson). Even before he created the device that would define 20th-century mass culture, Edison had earned the nickname “The Wizard of Menlo Park” (Menlo Park was a development in New Jersey where he housed his factories until 1887) for his ability to seemingly bring magic into the world. Brilliant, charming and energetic, Edison was a renaissance entrepreneur.

Born in 1847 (on February 11, which happens to also be my birthday), Edison lived until 1931, making him a contemporary of other great inventors of the turn of the 20th century, including Nikola Tesla (with whom he battled in the “War of the Currents,” making Tesla a sort of Bill Gates to his Steve Jobs) and Henry Ford. What an age that must have been! Still, as magnificent as his accomplishments were, Edison had his detractors. Primary among their complaints was the way in which Edison would patent inventions and then sue those who dared invent rival technologies. This came to a head in the early days of movies, when Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company sought a controlling interest in the nascent film industry, leading upstart producers to head West in an effort to evade Edison’s Trust. In his book Movie-Made America, the great film historian Robert Sklar accuses Edison of “greed and dissimulation” in his handling of patent disputes. So yes, he wasn’t perfect. But he sure had an impact, and mostly for the greater good.

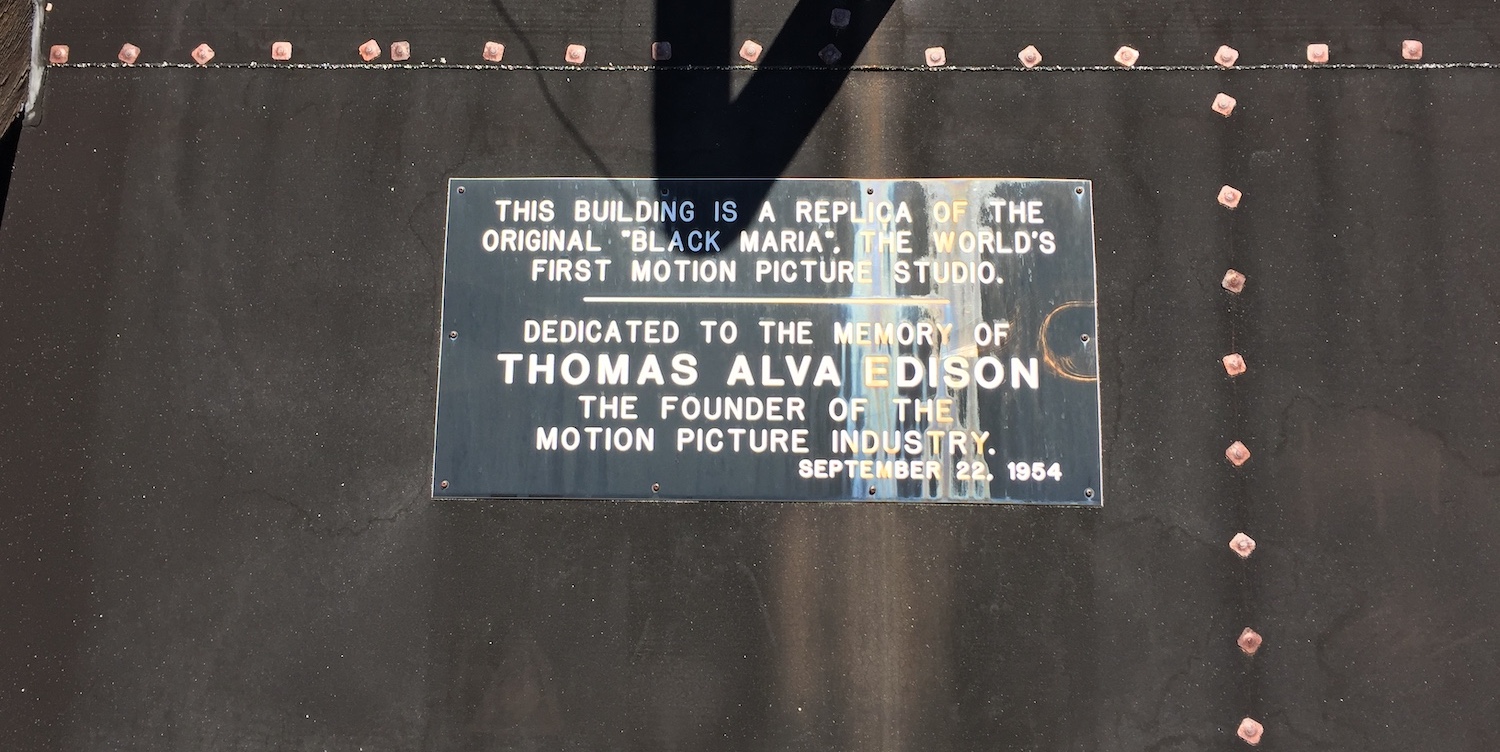

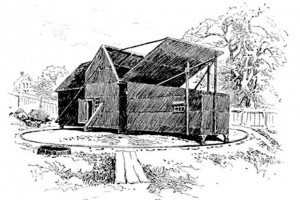

Recently, I brought a group of Stevenson University Film & Moving Image students to visit Thomas Edison National Historical Park, in West Orange, NJ (which is where Edison moved after leaving Menlo Park). It was here that Edison built his camera and the Black Maria studio, where the first motion pictures were shot in America (Auguste and Louis Lumière were simultaneously developing their own camera and projection system, in France). I didn’t know much about the park, beyond the fact that it had the Black Maria on site, so I was pleasantly surprised by the wealth of materials on display. From the replica of the Black Maria (built in 1954) – the original having long since fallen apart – to Kinetographs, Kinetoscopes, and Kinetophones, and more, the on-site museum, housed in Edison’s original warehouse and technical park, was impressive, indeed. We saw various iterations of the phonograph and its descendants, an early tattoo pen, and perhaps most grand of all, the actual production facilities of the laboratory.

It was wonderful to see 21st-century college students genuinely interested in 19th– and 20th-century accomplishments. Granted, these were film majors, so they already had a natural affinity for the subject, but I was unprepared for the level of enthusiasm. We had a great guide – Carmen Pantaleo, Park Ranger and Education/Group Tour Coordinator – which surely helped, but the facilities were the true star of the visit. And even though the Black Maria was not the original structure, seeing the replica helped all of us better understand how Edison and his team shot those early movies. I highly recommend this national treasure of a park to any and all, whether or not you have an interest in movies. Surely you have an interest in light, or sound (or tattoos) or any of the many other inventions for which Edison (or his staff) were credited. So get yourself to West Orange, and pay a visit to see where the Age of Filmcraft and Wizardry began.

It was wonderful to see 21st-century college students genuinely interested in 19th– and 20th-century accomplishments. Granted, these were film majors, so they already had a natural affinity for the subject, but I was unprepared for the level of enthusiasm. We had a great guide – Carmen Pantaleo, Park Ranger and Education/Group Tour Coordinator – which surely helped, but the facilities were the true star of the visit. And even though the Black Maria was not the original structure, seeing the replica helped all of us better understand how Edison and his team shot those early movies. I highly recommend this national treasure of a park to any and all, whether or not you have an interest in movies. Surely you have an interest in light, or sound (or tattoos) or any of the many other inventions for which Edison (or his staff) were credited. So get yourself to West Orange, and pay a visit to see where the Age of Filmcraft and Wizardry began.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)