(Gut Renovation world premiered at the 2012 Brooklyn Film Festival and is being distributed by Outcast Films. It opens theatrically at the Film Forum in New York on March 6, 2013.)

What is left to be said about Williamsburg, Brooklyn? Its cultural influence far outstrips the reality of the place, spawning countless think pieces and enough jars of artisanal pickles to outlast the zombie apocalypse. As a neighborhood it was old news long before HBO came calling, rebranding Sex and the City and moving it across the river. Hipsters have been trickling down the track marks of the L train for years—Bushwick has been Williamsburg for awhile, after Williamsburg was the East Village, and the East Village was Soho. New York artists move in migratory patterns dictated above all by rent, but also by space, and by community. I’ve never quite understood what people mean by gentrification (definition: “renovate and improve so it conforms to middle-class taste”). It’s such a judgy, self-righteous word, and much like hipster, it’s a label no one will cop to. I’m asking seriously: in what way do New York neighborhoods belong to anyone (or any group of people) in particular? To me it seems like constant flux, the vagaries and injustices of economics and politics building a history of tenancy as fat and layered as a pastrami sandwich. That is not how I wish things were, it’s just how they seem to be. I admire people who question their right to a place, but I wear my leases lightly. Claiming territory in New York is like asking to get your heart broken.

Filmmaker Su Friedrich has lived in a Williamsburg loft since 1989, a commercial space in a former iron works that she and fellow artists painstakingly built into a home. This sleepy coast of industry and artists’ studios was bound to change, and Williamsburg’s transformation into an enclave for the hip and wealthy began to speed up in the early 2000s, then exploded into steroidal growth when the neighborhood was rezoned for residential use in 2005. Combined with 25-year tax breaks, proximity to Manhattan, and “priceless views,” Williamsburg drew developers in swarms. Friedrich experienced these changes first-hand, and her response was to pick up a camera and begin filming.

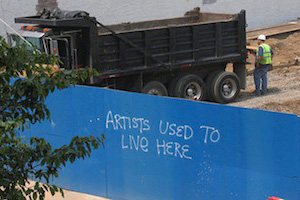

The resulting work is an intensely personal film, uneven and wildly biased. Friedrich has titled it Gut Renovation, which is somewhat of a misnomer. Unlike brownstone Brooklyn, what happened to Williamsburg is largely a story of demolition and destruction. The film’s title might more accurately describe Friedrich’s experience of losing her home and community. Urban scholars look elsewhere: Gut Renovation offers up nothing about Williamsburg’s history (or any facts or demographic data). It is a tone poem, a subjective and emotional distillation of anger and grief. Whether this works for you will depend on your empathy (or patience) with Friedrich. I found myself surprisingly moved. There’s something purely New York about Friedrich’s film that I responded to, and respect. It’s difficult to be objective about loss, far more human to record yourself hurling expletives out the window at nameless men with Bluetooths who have come to claim your future.

One of Friedrich’s more effective techniques in the film is her countdown of all the new condos that spring up, illustrated on map in red ink, as if she’s tracing the spread of a plague or a death toll. Watching old brick facades crumble in the steel maws of the machines has a certain poetry to it, but as one critic put it, “Gut Renovation is a film about ugliness.” That is not to say that Friedrich doesn’t have a sense of humor. She totes her camera along to countless open houses, discreetly filming the hapless buyers and real estate brokers giving the hard sell. She’s unafraid to skewer them for their corny taste, and the depressing and utterly pedestrian mediocrity of their vision of life in Williamsburg. Friedrich hates these “rich people,” and also the “fancy dogs” that waddle after their owners down the overcrowded sidewalks. She’s cranky and aggressive, which I thoroughly applaud, even if it’s reductive and unfair. You don’t like it? Go back to the suburbs. Oh wait.

One of Friedrich’s more effective techniques in the film is her countdown of all the new condos that spring up, illustrated on map in red ink, as if she’s tracing the spread of a plague or a death toll. Watching old brick facades crumble in the steel maws of the machines has a certain poetry to it, but as one critic put it, “Gut Renovation is a film about ugliness.” That is not to say that Friedrich doesn’t have a sense of humor. She totes her camera along to countless open houses, discreetly filming the hapless buyers and real estate brokers giving the hard sell. She’s unafraid to skewer them for their corny taste, and the depressing and utterly pedestrian mediocrity of their vision of life in Williamsburg. Friedrich hates these “rich people,” and also the “fancy dogs” that waddle after their owners down the overcrowded sidewalks. She’s cranky and aggressive, which I thoroughly applaud, even if it’s reductive and unfair. You don’t like it? Go back to the suburbs. Oh wait.

One of the sly touches in Friedrich’s film is her attention to detail, which is on sharpest display in regards to the marketing of the new buildings in “Condoburg.” Aqua, Ikon, Lucent, Aurora, Jardin: phony names that seek to distinguish one glassy behemoth from another, though Friedrich’s rapid montage of sample units shows their fundamental similarity. I share Friedrich’s irritation with the hype, from the catered cocktail parties for prospective buyers to the pervy, sexist marketing promoting Williamsburg’s “wet dream” over a lazy stock image of a woman in a bikini. Other language touts the “real neighborhood” and “unexpected charms,” a condo as an expression of “your own authentic style” that still allows you to “live above it all.” Friedrich is right to feel insulted by this attitude.

Friedrich’s scorn and anger are of course paired with grief. She stands helpless as friends and business owners are evicted, and eventually her number is up as well. She and her partner agonize over where to go, mourning the 37 roommates and countless parties they had over the years. She briefly interviews her mechanic, who has one month to vacate after 26 years of business, and a Polish butcher forced out after almost 40 years. I wanted to hear more from Friedrich’s displaced neighbors. The weakest part of Friedrich’s film is its somewhat myopic view. Having missed the gritty years, I find it difficult to get worked up about this nostalgia (“where will the artists have acoustic guitar jams and dinner parties in silly hats??”), and I had to laugh when she likened Ridgewood, Bed-Stuy, and Sunnyside (where I live) to “the Moon.” Her choice of music is equally dramatic, though Teddy Pendergrass’ “I Don’t Love You Anymore” is inspired. Is it Friedrich who doesn’t love Williamsburg anymore, or the other way around? The film never reveals where she ends up, though subsequent reading seems to place her in Bed-Stuy. The Moon, after all.

Friedrich’s scorn and anger are of course paired with grief. She stands helpless as friends and business owners are evicted, and eventually her number is up as well. She and her partner agonize over where to go, mourning the 37 roommates and countless parties they had over the years. She briefly interviews her mechanic, who has one month to vacate after 26 years of business, and a Polish butcher forced out after almost 40 years. I wanted to hear more from Friedrich’s displaced neighbors. The weakest part of Friedrich’s film is its somewhat myopic view. Having missed the gritty years, I find it difficult to get worked up about this nostalgia (“where will the artists have acoustic guitar jams and dinner parties in silly hats??”), and I had to laugh when she likened Ridgewood, Bed-Stuy, and Sunnyside (where I live) to “the Moon.” Her choice of music is equally dramatic, though Teddy Pendergrass’ “I Don’t Love You Anymore” is inspired. Is it Friedrich who doesn’t love Williamsburg anymore, or the other way around? The film never reveals where she ends up, though subsequent reading seems to place her in Bed-Stuy. The Moon, after all.

New York has always swung crookedly between luxury and poverty. It remakes and reinvents itself without permission, and that freedom is arguably what draws people here. Still, records of the past remain, and I love spotting them in movies: Soho in Scorsese’s After Hours, the East Village in Susan Seidelman’s Smithereens, and of course Williamsburg in Tom DiCillo’s Johnny Suede. If they shine a bright, overly filmic light on those neighborhoods, they still capture the texture of New York’s past. Gut Renovation happens much later, when the critical mass of artists has moved on, less cinema than glum reality. Still, I relish the thought of Friedrich’s film screening at the Film Forum, and the post-screening kvetching that will go on in the lobby. Bring a pastrami sandwich and enjoy the show.

— Susanna Locascio