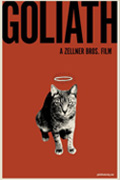

(Goliath is now available on DVD. Visit the film’s official website to watch the trailer and learn more.)

There is a shot in David and Nathan Zellner’s Goliath that lasts for about the same duration as most of the short films that made the fraternal duo so beloved on the festival circuit, and which, on its very own, lifts this feature from the cradle of absurdity in which those films kicked and screamed and carries it to a level of comedy so deadpan that it is practically stoic. The shot involves the nameless, hapless male protagonist meeting his wife at her lawyer’s office to sign off on their divorce. To describe the scene any further would be to spoil the gag, which is itself a distillation of a joke into its most basic elements. On its own, this moment could be considered a study in the chemical components of a comic set-piece; coming as it does roughly at the mid-point of the story, it serves as a pivot point for a film that swings from farce into ever-deepening levels of discomfit.

Fans of the Zellners’ short films will find much that’s familiar here: the Austin locale, the lovely photography by Jim Eastburn, the Zellners themselves in starring roles. What some may not realize is that this is not, in fact, the brothers’ first feature film; in the late 90s they made an oddball 16mm comedy called Plastic Utopia, which I once upon a time had the pleasure of seeing projected with the reels out of order. This was followed by Frontier (unseen by me), a science-fiction fable shot entirely in a made-up language of Bulbovian. Then came the short films, which became perennial mainstays in the Sundance lineup and which, over the course of four or five years, saw their helmers’ idiosyncratic voices break, their funny bones grow into maturity. Their work became instantly recognizable and unqualifiably unique—not to mention increasingly mordant. A strange, bitter sensibility was stirring in even their goofiest of outings, and it is this sense of anti-pathos that blooms into full blown bittersweet misanthropy in Goliath. Their observant style calls to mind the old cinematographers’ adage about lens lengths: what’s a tragedy in close-up becomes comedy in a wide shot. Suffice to say, this is a film with a lot of wide shots.

The film begins as an account of a mid-life crisis, in which the protagonist (David Zellner) loses the two things that make him a man: his wife, who leaves him, and his livelihood, from which he’s demoted. He’s quite the sad-sack; he goes home at night, eats permanently shrink-wrapped microwave meals, watches internet porn, and tries to pretend that someone might care that he’s smoking indoors. Already emasculated, he discovers one evening that his one remaining point of validation—his beloved cat Goliath—is missing. “Here, kitty-kitty-kitty!” he calls out, holding the electric can opener out the window, sending a warm, beckoning whir into the night air that will go unanswered.

The film begins as an account of a mid-life crisis, in which the protagonist (David Zellner) loses the two things that make him a man: his wife, who leaves him, and his livelihood, from which he’s demoted. He’s quite the sad-sack; he goes home at night, eats permanently shrink-wrapped microwave meals, watches internet porn, and tries to pretend that someone might care that he’s smoking indoors. Already emasculated, he discovers one evening that his one remaining point of validation—his beloved cat Goliath—is missing. “Here, kitty-kitty-kitty!” he calls out, holding the electric can opener out the window, sending a warm, beckoning whir into the night air that will go unanswered.

And so the film ostensibly becomes the story of a man on a mission (and, resultantly, turns into an acute study of Freudian transference). The Zellners, consciously or not, understand how a pet can change one’s perception of a person. Just as one can move an audience to tears by wringing a puppy’s neck, so too can one create great sympathy for an unlikable character simply by showing him doting on his beloved kitty. Hence, they’ve given themselves free range to make their hero a loser through and through; furthermore, unlike other cinematic losers before him, he isn’t put-upon. He’s brought his misfortunes down upon himself (as exemplified in a horrifyingly hilarious scene in which he angrily pits his own infidelities against his wife’s). He’s sad, pathetic, and nearly entirely unsympathetic, but because he loves Goliath, we like him, relate to him. We’d laugh with him, not at him—except that he never actually laughs, and so we’re left stranded mid-chuckle.

That’s how the humor in the film works. It exists in an uncharted grey zone, on its own wavelength, which is why the shot I described in the first paragraph is both hilarious and rather sad. Half the shot is a build-up to a joke, and the other half deals with the substantial fallout, and throughout it all the Zellners maintain the same, steadfast tone. It takes guts to pull off a shot like that. The same goes for the ensuing last act of the film, in which, after learning the truth about Goliath’s fate, our hero fashions his life’s myriad woes into a righteous anger and sets out on a mission of vengeance. What happens at the climax of the film occurs on a slippery slope of truly disturbing behavior, but because the Zellners approach it from the same rigorous perspective as the rest of the film, the morality of the situation places distant third to the emotional veracity of the moment, which itself is compacted by its overall absurdity. It’s not exactly safe to laugh, but it’s pretty hard not to.

— David Lowery

Pingback: Hammer to Nail » Blog Archive » Monday Short Film Pick 8/9/2010 – FLOTSAM/JETSAM