(Cinema Guild’s Aurora opens at IFC Center in New York on June 29th, 2011. Visit its official website for more information.)

An early conversation in Aurora finds a man named Viorel and an unnamed woman talking about Little Red Riding Hood—specifically, whether or not the grandmother should be clothed when she’s cut out of the wolf’s stomach. This exchange, like many other moments throughout Cristi Puiu’s film, appears pedestrian in both delivery and substance (and many will no doubt interpret it as such) but is spoken in a way that demands to be mined for deeper meaning. To understand and be willing to accept that larger implications exist in Aurora‘s many small moments is one’s only hope of making it through a film that, like its predecessor The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, is at times Jeanne Dielman-esque in its insistence on vérité depictions of mundane activities carried out in real time and loaded with allegorical meaning. So deliberate and observational is Puiu’s approach that it can be easy to forget that his film is above all else a subjective experience requiring a great deal on the part of the viewer and not, as it may seem, a simple endurance test. To view this film under the assumption that those fragments shown onscreen amount to more than the smallest pieces of the puzzle is not only contrary to Puiu’s intent but cause for disaster, as Aurora does not reward a surface-level viewing in the slightest.

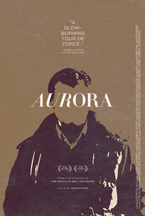

Viorel, our eventually-violent cipher of a protagonist, is essentially a blank canvas onto whom we may project sympathy, disgust, or even indifference. Puiu (who plays Viorel) either willfully refuses to or simply has no interest in contextualizing his character with more than the slightest exposition, and so it’s left almost entirely up to us to decide what to make of him. (Indeed, one of our greatest clues toward understanding Viorel comes in Aurora‘s poster, on which he is literally faceless.) He could be any number of things, most of them criminal in nature, and in his dual unknowability-universality he becomes a veritable Rorschach blot: Is he good? Evil? Neither? Any conclusions reached will likely have as much to do with the viewer as they do about the film itself, which seems to be Puiu’s aim. His film is a reciprocal affair which the audience must work as diligently to interpret as he did in creating it. This technique is certain to alienate many, but those willing to meet Puiu halfway (all right, maybe 2/3 of the way) will find that Aurora is, if not always a thrill to watch, certainly great fun to ponder. Its scant narrative is conducive to a certain meandering, and it’s out of one’s own headspace that Puiu means for the real work to be done.

The film is almost entirely unadorned by music (Eifel 65’s “Blue” is a notable exception) and showy camerawork, the result of which is to make us feel as though we’ve stepped into the room with Viorel mid-conversation—a (non-)stylistic flourish that both accounts for, and helps do away with, some of the confusion that inevitably comes with watching the film. We often glimpse Viorel from the other side of an open doorway, his body partially or entirely out of view; the frequent feeling of seeing-but-not-seeing him further underscores how little we actually know of him. We witness everything Viorel does in almost excruciating detail, but are almost always at sea in terms of the impulses driving his increasingly cold, calculated actions. To think him a mere sociopath is tempting, but it almost seems too easy an interpretation—as though to do so is somehow failing to look beyond the blank expression and menacing laconicism that might mask an even more sinister core. Voriel is deeply untrustworthy and paranoid, and following his every move for three hours inspires similar feelings on the part of the viewer.

The film is almost entirely unadorned by music (Eifel 65’s “Blue” is a notable exception) and showy camerawork, the result of which is to make us feel as though we’ve stepped into the room with Viorel mid-conversation—a (non-)stylistic flourish that both accounts for, and helps do away with, some of the confusion that inevitably comes with watching the film. We often glimpse Viorel from the other side of an open doorway, his body partially or entirely out of view; the frequent feeling of seeing-but-not-seeing him further underscores how little we actually know of him. We witness everything Viorel does in almost excruciating detail, but are almost always at sea in terms of the impulses driving his increasingly cold, calculated actions. To think him a mere sociopath is tempting, but it almost seems too easy an interpretation—as though to do so is somehow failing to look beyond the blank expression and menacing laconicism that might mask an even more sinister core. Voriel is deeply untrustworthy and paranoid, and following his every move for three hours inspires similar feelings on the part of the viewer.

Aurora is the second in a planned series of loosely related films entitled Six Stories from the Outskirts of Bucharest, and Puiu touches on the same sort of Kafkaesque bureaucracy that propelled much of Mr. Lazarescu‘s plot just enough to remind us that Aurora inhabits the same cinematic universe. This occurs most notably in a scene that culminates with Viorel’s most revealing statement: “You seem to think you understand. You seem to think you follow what I’m saying. And that scares me.” After nearly three hours of struggling to get a sense of who this man is, the effect of this much-needed monologue is practically devastating. Here Puiu displays a degree of self-awareness in acknowledging his character’s unknowability and, more frighteningly, reveals that not even Viorel is fully capable of expressing his true nature. He’s as much a mystery to himself as he is to us, the kind of man who might take pause at the sight of his own reflection for fear of waking the monster within.

— Michael Nordine