A Conversation with Joel Edgerton (BOY ERASED)

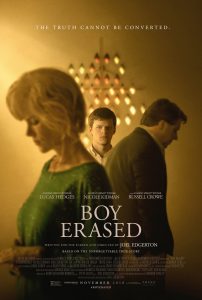

I met with writer/director/actor Joel Edgerton (The Gift) on Saturday, October 20, 2018, at the Middleburg Film Festival, to discuss his feature adaptation of Garrard Conley’s eponymous 2016 memoir, Boy Erased (which I also reviewed). The film is brisk and efficient in its storytelling, which serves the raw emotional power of its narrative extremely well. With a great central performance by rising star Lucas Hedges, and fine supporting work from Russell Crowe (The Nice Guys) and Nicole Kidman (The Beguiled), and Edgerton, himself, the movie offers a fine showcase of Edgerton’s talent both behind and in front of the camera. It also tells an extremely important tale of the horrors and dangers of gay-conversion therapy. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, since you’re Australian and you have two other Australians in the film, I have to ask you, when do you think American actors are going to start going to Australia to play Aussies? There are all these Australians in America!

Hammer to Nail: So, since you’re Australian and you have two other Australians in the film, I have to ask you, when do you think American actors are going to start going to Australia to play Aussies? There are all these Australians in America!

Joel Edgerton: Well…

HtN: That’s a joke question.

JE: Yeah, but it’s interesting because all the while I was growing up, wanting to get into movies – trying to get into Australian movies – there were so many British and American actors coming to Australia to be in movies, generally as American or British characters. And it was a way for local filmmakers to get their films financed, to bring bigger stars to Australia. And then, you know, it’s people like Russell and Nicole, and earlier than that, Mel Gibson, and…

HtN: Judy Davis.

JE: Judy Davis, you know, who were going over to America and being part of American movies. I guess that’s what all of us want to do, is go play in the biggest pond possible.

HtN: Yeah. I kept on waiting for Guy Pearce and Toni Collette to show up, as well.

JE: Yeah, they…(laughs)…Troye Sivan is the other Australian in it. He plays one of the kids in the therapy, the kid with the blonde hair. He’s a very famous young pop star and wonderful young actor. And it turns out that Flea was born in Victoria, in Melbourne.

HtN: Well everyone’s terrific in it. So, I really like how you do the actual on-screen erasing title of the movie at the start. How did you come up with that design for your title card?

JE: It was actually one of our editors, Mike Selemon, who we call Money Mike. He’s one of the assistant editors. Jay Rabinowitz is my editor and worked so closely with Money that he would like to have just shared the credit with him. So, that was just something that Money had done as sort of a little cute early idea when we were cutting, and it just stuck.

HtN: Well, it works, and of course it’s appropriate to the film. So, speaking of the way things are made, I also really like your choice of opening shot of the back of Lucas Hedges’ head, in close-up. It sets up a lot about his being erased, and lack of identity, or struggle for identity. Did you always know you wanted to open the film that way? It’s a really evocative first shot.

JE: Yeah. I mean, it’s almost like plugging into a character sometimes. Being behind somebody is a way to begin that relationship with an audience, where they get to – whether it’s the beginning of the film or throughout the film – they get to project their own feelings into a character. If you can’t see their face, you paint your own emotion onto them. And being behind someone’s head, I always find fascinating. There’s something eerie about it.

In this case it was almost like a way of just plugging into him and introducing him. You know, I’d had this idea halfway through the edit. I was like, all right, we meet this kid when he’s 18. And I wanted to get a sense of who he was before, and for the audience to have some touchstone with him, and I just had this thought about reaching out to Peter Hedges, who’s Lucas’s dad, and his wonderful mother, and say did you film him much as a child? Because the early footage of him, which is the true opener…

HtN: That was going to be another question. That footage in the opening is actually young Lucas?

JE: It’s actually Lucas as a three-, four-, five-year-old. I got filmed a lot as a kid on an old Beta camera, you know, my soccer matches and all sorts of stuff. And the parents nowadays on iPhones film their children so much. And why do we do it? Because we love them so much, and we’re so in awe of them. So, why I loved the idea of starting with that footage is: a) it’s the real young Lucas and we see him at a pre-sexual stage, and the mere fact of his being filmed constantly by a parent is that they idolize him. And then: b) just to then just snap to an 18-year-old boy who seems to be in turmoil, with his mother calling him down for breakfast, has a sense of tension about it, and then we see this like really dark cloud hanging over the breakfast table as an opener.

HtN: Right. And then to cut to the back of his head rather than the face when we’ve just seen him. Another production question: your film has many really intense emotions, but one of the things I admire about it is that you’re actually telling the story with relative restraint.

JE: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

HtN: So, your filmmaking style sort of goes against some of the histrionics that could erupt, and I really think it works well in opposition to the turmoil. Could you talk a little bit about your decision to take such a restrained approach?

Our Chris Reed and Joel Edgerton

JE: Well, in all my research of conversion therapy, there were things that I had discovered that I was like, wow. Like, this could be interesting to put in the movie. I mean, you know, stories of almost out-and-out torture. And that stuff does exist. I resisted doing it, because I was telling Garrard’s story, and Garrard’s institution had this different kind of insidiousness to it, because it was about filling people, families and the kids who were under the therapy, with these sorts of really dangerous ideas. To tell somebody that homosexuality is a chosen behavior, based on dysfunction or trickle-down family sins is such a complicated and dark seed to plant in somebody’s head that leads to all sorts of crazy stuff.

And suicide, you know, is the end road for a lot of kids who go through therapy. I mean, one of the darkest practices in the film is this sort of exorcism, and that’s true of Love In Action [the name of this specific conversion-therapy practice]. They would perform these fake funerals, where they would create a kind of alternate narrative to the endgame of a child’s poor choices, in their mind. So we included that, but we resisted the actual pure physical torture that I’d read about.

And part of that reason, too, is that in Garrard’s book – why I thought it was worth making into a movie – there’s a redemptive space at the end, because his parents had a realization that they didn’t exercise their duty of care by researching the place. They hadn’t sent him to a torture facility willingly. They thought they were doing things to help him, and that even the therapist thought they had an actual possibility of success. And that margin of sort of relative corporate safety, albeit dysfunctional, meant that they weren’t just profiteering and torturing children. His story felt to me ultimately hopeful.

HtN: So, how did you first come across the book Boy Erased, and initially become hooked by it?

JE: My agent had sort of become a manager, and moved to Anonymous Content, and I was just given the book. They were totally unaware how fascinated by institutions I was, and the fear I had as a child of being institutionalized. I’d heard about conversion therapy, and I was like, oh, here’s a prison, or an institution that I’ve never really discovered, in detail. And knowing that this boy had written a memoir about his experience there, I was like, I have to read this. So I guess I had a morbid curiosity akin to driving slowly past a car accident. That human interest we have in other people’s pain, not out of cruelty, but just out of curiosity. And the book actually made me feel very emotionally connected to a family story, and that second part of it was why I thought it was worth turning into a movie.

HtN: That’s interesting. You share that with Hitchcock, who had a lifelong fear of being falsely imprisoned.

JE: Really.

HtN: Yeah.

JE: Wow.

HtN: Well, thank you so much, Joel. I really appreciated talking to you, and I really liked the film.

JE: Thank you very much!

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)