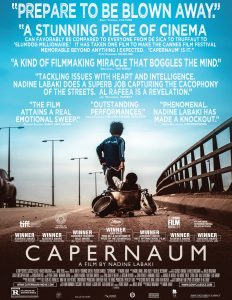

A Conversation with Nadine Labaki (CAPERNAUM)

I met with Lebanese director Nadine Labaki (Caramel) on Saturday, September 8, 2018, at the Toronto International Film Festival, to discuss her Cannes Jury Prize-winner, Capernaum (original title “Capharnaüm”) (which I also reviewed). The movie, shot with non-actors from Beirut’s refugee settlements, tells the story of a 12-year-old boy, Zain (played by Zain Al Rafeea), who sues his parents for giving birth to him, so determined is he to make sure no one else lives the same miserable life he has. Despite that depressing premise, it’s a film both harsh in its condemnation of the way established societies treat migrants and life-affirming in its portrait of resilience and resistance. As tragic as it is, it is also quite humorous, at times, thanks mostly to Zain’s outsize personality (in such a tiny body!) and performance. Here is a condensed digest of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So, let’s start with this: what is the significance of the title, Capernaum?

Hammer to Nail: So, let’s start with this: what is the significance of the title, Capernaum?

Nadine Labaki: Originally, it’s in French. “Capharnaüm” means chaos, and it’s used in French literature to signify chaos. It’s a biblical village and it was cursed for being too chaotic, or something like that. And then in history, we started using it to signify chaos, hell, disorder. So, for me, the title came up even before we started writing the script, when I put on the board all the different themes that I was obsessed with at the moment. Between children’s rights, and injustice with these children, the absurdity of borders, absurdity of having to have a paper to prove that you exist and all that. So, I put all this on the board and at one point I look at the board and I say this is like Capharnaüm, this is hell, we’re living in hell. That’s how the title started. And in English, Capharnaüm is translated into Capernaum.

HtN: So, I was at the opening screening last night and I heard your rather detailed description of the genesis of the project. Given that we are slightly limited for time, now, I was wondering if you could give a brief recap of how you came about the idea?

NL: I think I’m not the only person being moved by the sight of all these children that we see everywhere, and it’s a problem that we see in all the big cities in the world with these economic and refugee crises, and the number of children in child labor, the number of children…paperless children, is growing by the millions now. There’s no specific statistic, no specific numbers, because every time you get to that point they tell you there aren’t numbers and we are not able to do specific statistics because they don’t want to acknowledge the problem, but the problem is huge.

So, I don’t think I’m the only one being moved by that, and I wanted to turn this anger into something, and the anger towards this injustice towards kids that are really the only ones…not the only ones but the most fragile ones to be paying the price of our failed systems or our failed societies, and they didn’t ask to be here, they’re just paying the price, they’re just being punished. And this is what they feel, also, they feel like they’re being punished for somebody else’s faults and they never asked to be here, so I just wanted to know more, so I started researching and talking to kids, and wanting to know more. This is what they tell me when you talk to them, and I used to ask them are you happy to be alive? And most of them used to tell me no, why am I here? I didn’t ask to be here. So, it’s all inspired by that and it was important for me that I’m able to maybe learn more and try to understand and try to somehow tell that story.

HtN: Perhaps you should next turn your attention to the American border with Mexico and tell that story.

NL: This is deeply horrific, I don’t know how we can allow ourselves to get to that point. How does a human brain function at that point? How do the governments function? Do they not have any children, any hearts? It’s completely insane how human nature becomes so ugly.

Director Nadine Labaki

HtN: Sadly, it’s not the first, and probably not the last time. So, let’s talk about the casting process, because really, your child actors in particular, young Zain, are just amazing. How did you find him and the others?

NL: The casting is something that was a very long and difficult process. I have a team of casting recruiters that go everywhere in Lebanon to interview people and interview kids and talk to kids on the street. We’ve seen every kid on the street in Lebanon, so they interviewed a lot of kids and Zain was one of them, and when I saw the tape – he was playing with his friends in the streets – it took me literally two minutes to know that it was him. His eyes, his…he’s exactly what I had written, the character I had written, and 4 years ago, even before meeting Zain I had drawn the face of a child shouting at adults, and when you compared two images, it’s exactly Zain, and it was Zain even before I knew him.

So, for me, it was him, he’s a miracle child. He’s a Syrian refugee. Of course, he escaped the war in Syria, he came to Lebanon, he’s been living for the past 8 years in Lebanon in very, very difficult circumstances and he didn’t go to school, he grew up on the streets and growing up on the streets, you see so much. You see so much violence, you see so much abuse. He was personally exposed to a lot of things and he has this wisdom of children who have lost their childhood, who have become adults, and that’s how he was able to be so good. Because he was doing something he knows.

HtN: He’s an old man in a little boy’s body, in many ways.

NL: Exactly.

HtN: So, you say he’s Syrian, but in the film he’s making fun of a Syrian accent. Are the bulk of your characters supposed to be Palestinian refugees, Syrian refugees, something else?

NL: In the film, there are many differently nationalities.

HtN: That’s what I figured.

NL: With Zain, you don’t know what his nationality is because it’s very symbolic also, because he’s paperless. He doesn’t have any papers, so we don’t know what his identity is, and we don’t say it and it doesn’t matter. And for the rest of the characters, you have Maysoun, who is a Syrian refugee, you have the parents, who you don’t know where they’re from. It’s not specifically defined, the only one that’s really defined is the small girl, who is a Syrian refugee. And the Ethiopian girl.

HtN: So, speaking of casting, you put yourself in the film in a small role as the lawyer. That was an interesting choice, and it makes sense in a way because you’re defending Zain’s rights. What made you do that?

NL: In the beginning, my role was much bigger than that and it was exactly that, defending Zain and being as close … because everybody is very close to their own reality. So, for me, as I was working, during these 4 years, I was very eager to defend them, and the way I was talking about this problem to people and the way I was defending their cause, I found it normal that I was going to be the one who was going to defend Zain. And the role was much bigger than that, and I had a speech at the end and all that. But later on, I just felt less…I felt I was cheating. I felt I…I’m not a real lawyer, I can’t be a real lawyer, and everybody else was playing their role. So, for me it was normal that I was not supposed to be in the film, that’s why my role was very, very short and it’s just an appearance so you understand how he got to a point where he sues his parents.

A Still from “Capernaum”

HtN: So, I heard you say last night that you had over 500 hours of footage, which is incredible. It’s more a documentary ratio than a narrative fiction film ratio. And you worked with editor Konstantin Bock, who was the man on stage last night with you. How long did it take to cut this down?

NL: The first draft was 12 hours long.

HtN: (whistling) You should do it as a Netflix series! (laughs)

NL: (laughs) And then, from the 12 hours you start trimming and trimming and trimming and it was a very long process, it took 2 years of editing in order to get to this point and I’m still having a hard time letting go. There’s so much in this film, there’s so much footage, there are so many beautiful moments, so many treasures that it’s difficult to say OK, I’m going to take this out. So, I’m still…at this point now, the film is out, it’s almost going to be released in theaters and I’m still holding on and it’s still very difficult to let go. So, it was very difficult for everybody who was also working on this film to try and find the right pacing, the right rhythm. What do we keep? What do we take out? The film was almost rewritten in the editing room.

HtN: I can imagine, plus I’m assuming some of the performances were improvised.

NL: There was a lot of improvisation, a lot of…because I wanted to bring their own truth to the film and it was impossible for me to give them a script that they memorize. It was impossible for me to do that and I don’t believe in this kind of situation. I just needed to believe in what these people were saying, so I needed it to come out of their mouths as if it was theirs, and each one brought his own experience, his own suffering. When the parents are expressing themselves in the court, it is them expressing themselves. It was not the characters of the film. I needed to hear it from their own voices, their own experiences, to believe in what we were doing. I didn’t want to feel like I was manipulating the story.

HtN: Of course. That’s interesting that you still can’t let it go, but it’s picture-locked right now, correct? Sony Pictures Classics have picked it up, so it won’t change, will it?

NL: It won’t change, but it’s difficult to say that it’s finished.

HtN: I understand. So last night at the Q&A you also talked about how some of the cast members were in fact arrested for having no papers, just as in the movie.

NL: Rahil, the Ethiopian girl, was arrested a few days after the scene where she gets arrested. She was arrested exactly the same way, and she lived through the same circumstances, and also the parents of Treasure. [The baby boy] Yonas is actually named Treasure, in real life.

HtN: And Treasure is actually a girl?

NL: She’s a girl. And she also was living in the same situation, she is the daughter of the two migrant workers who were living illegally in the country, and because they’re also migrant workers they’re not allowed children. So, she was born in Lebanon, and because they are not allowed, she was not registered, she was not declared, so she was an invisible child, exactly like in the film. Exactly like in the film, the parents were arrested with Rahil because on the shoot they got to know each other so they were at a party together and there was a raid and they took everybody, and they took the parents, too. So, when we were shooting Treasure in the film, shooting the scenes where she is without her mother, she was actually without her mother in real life. She was with us; the casting director took her in and took care of her.

HtN: Well it’s a remarkable film, and I’m really glad I got a chance to see it. Congratulations!

NL: Thank you so much.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Jay S

Nadine Labaki manipulated the hell out of this story SMH…Who is she to suggest that lower-income families shouldn’t have children??

Chris Reed

Did you see the movie? That is not her thesis at all.

Pingback: 50 of the best movies directed by women - One News USA