THE LOVE THAT REMAINS

(The 63rd New York Film Festival (NYFF) ran September 26-October 13 via Film at Lincoln Center. Check out M.J. O’Toole’s The Love That Remains movie review, fresh from the fest! Seen it? Join the conversation with HtN on our Letterboxd Page.)

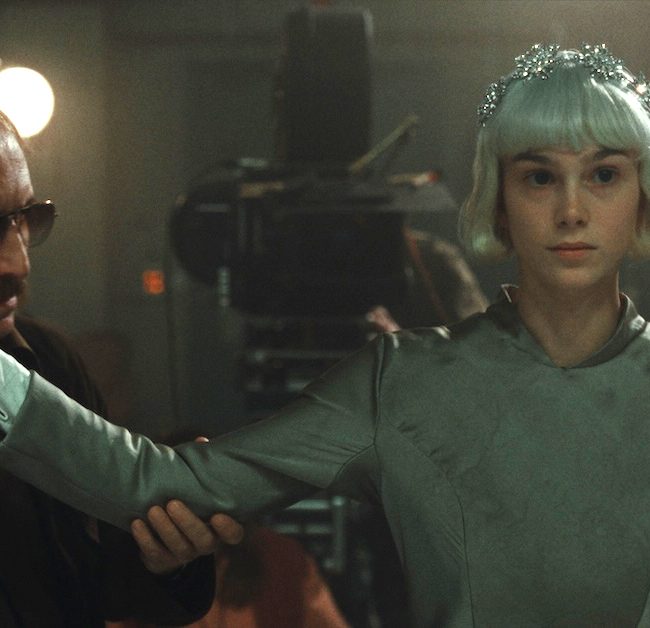

As the seasons change, life flows on like the breathtaking Icelandic seas. Writer/director Hlynur Pálmason offers a reprieve from the overcast skies of human despair he portrayed in his previous films, offering a more loving look at the ties that can truly bind. His fourth feature, The Love That Remains, captures a year in the life of a family in the throes of marital separation. Unlike his last two films, the magnificently bleak Godland and the more intense A White, White Day, Pálmason takes a 180° turn here with upbeat humor and greater compassion for his characters. It is easy to fall in love with the mother, father, and their three wiseass kids at the center of this family drama. However, one thing that Pálmason continues to make just as prevalent in his films is the spectacular Icelandic landscapes, which he masterfully captures on 35mm in a 4:3 ratio, serving as his own cinematographer. As the grass blooms and the ocean freezes over the course of one year, our family lives and loves the best they can against the rising tide.

Sweethearts since their teenage years, married couple Anna (Saga Gardarsdottir) and Magnús (Sverrir Gudnason) have already been separated by the time the story starts. Though they never give a concrete reason for their circumstance, the word “separated” is used loosely in their case. They maintain a close, amicable bond for the sake of their three kids: teenager Ída (Pálmason’s real-life daughter Ída Mekkín Hylnsdottír), and younger sons Grímur (Grímur Hlynsson) and Þorgils (Þorgils Hlynsson–pronounced ‘Thorgils’), not to mention their sweet Icelandic sheepdog named Panda (winner of the Palme Dog award at this year’s Cannes). Magnús (or Maggi) still comes over to the family home, hoping to be close enough to his children. He continuously makes playful advances towards Anna, which she gently turns down so as not to confuse their kids. Though whenever he’s out at sea working on a fishing boat, Anna takes on the bulk of parenting while trying to juggle her career as a metal sculptural artist. Due to their careers and living arrangements, Magnús feels more like a houseguest than an involved father. While both parents are endearing in their own ways, they have different outlooks on how their kids should be raised. Anna is more chill with her kids swearing like sailors and listening to suggestive content, while Magnús thinks she goes too easy on them. The dynamic that Pálmason creates between the two parents isn’t a case of who’s more patriarchal versus more gentle. They do see eye-to-eye on a lot of things, but Anna’s ambitions and Magnús’ increasing self-doubt are certain factors that keep them from fully expressing what they need to.

As the film progresses, it plunges more and more into visual surrealism. In some ways, it emphasizes the beauty of the land the family lives on. In other ways, it expresses the state of mind of certain characters, primarily Magnús. One unforgettable fantasy sequence is when he imagines himself blissfully shrouded in Anna’s bright dress during a family outing, highlighting the obvious love he still has for her. Working as his own cinematographer, Pálmason succeeds in crafting visuals as a metaphor for his characters’ states of mind. You can’t help but feel for Magnús as he becomes more tormented by his unreciprocated romantic feelings, as well as his belief that he has let his family down somewhat. Gudnason’s layered performance as someone struggling with himself conveys a mixture of joy (in moments where he finds it) and quiet poignancy. The kids are given the spotlight as well. With their rascal-like antics, they are the film’s biggest comic relief. One thing all three kids do to pass the time is practice their archery skills on a scarecrow-like knight, which ultimately becomes a symbol for the passage of time. With Pálmason steadying his camera on all of them using wide shots, he gives his young actors the space to be themselves. One violent incident that eventually took place certainly elicited an audible gasp in the theater, but instead of it being a dramatic turn, it’s more of an unforeseen challenge that the family gets through together, unexpectedly bringing out some laughs.

With The Love That Remains, Hlynur Pálmason has accomplished the rare feat of making a slice-of-life dramedy with the right amounts of beauty and mysticism. While comparable to films like The Squid and the Whale and Boyhood, which show the nasty effects of a family fracturing, Pálmason’s fourth feature shows how unconditional tenderness can bring people together and conjure a sense of hope even in the most random circumstances. He doesn’t give concrete answers as to how Anna and Magnús’ marriage will turn out, or if the characters will find peace and acceptance, but that uncertainty is what life itself is. Through experiencing both the good and tough times, you’ll walk out feeling soothed and with a reminder not to take the important things for granted. The entire ensemble knocks it out of the park in their respective roles, and Pálmason shows his versatility as a filmmaker with this meditative and life-affirming feature.

– M.J. O’Toole (@mj_otoole93)

2025 NYFF;Hlynur Pálmason; The Love That Remains movie review