(Check out Chris Reed’s Nuremberg movie review, it’s in theaters now! Seen it? Join the conversation with HtN on our Letterboxd Page.)

When the Allied forces defeated the Nazis to end the European side of World War II, they then had to decide what to do with those German prisoners who had either surrendered or been captured (Hitler, Himmler, and Goebbels had taken the easy way out via suicide). There had never before been an international tribune to litigate crimes against humanity. The trials that would take place in Nuremberg over the course of a year, beginning in the fall of 1945, established conventions that have served as models for similar prosecutions ever since. Without Nuremberg, there is no International Criminal Court in The Hague.

In his sophomore feature, Nuremberg, writer/director James Vanderbilt (Truth)—adapting Jack El-Hai’s 2013 history of the period, The Nazi and the Psychiatrist—explores the challenges faced by those who set out to prosecute the Nazis. As represented here, many among the Allies wanted to hang or shoot German commanders and soldiers without ceremony, especially once the facts began to emerge about their genocidal actions towards Jews and others. And who would have blamed them for so doing? It is to their credit that they sought a legal framework to justify any subsequent punishment.

This was especially important given how the Nazis had perverted the law to excuse their own actions, twisting and perverting rules and regulations until up was down, right was wrong, and truth was fiction. Notwithstanding that France, Great Britain, and the United States were at that time in partnership with the Soviet Union—a country also known to distort reality to suit its ideological needs—the Allies felt the need to reclaim basic humanitarian principles to establish a (hopefully better) new world order. When Nuremberg sticks to these issues, it is at its cinematically and thematically strongest.

Central to the movie’s narrative—as per the source text—is the battle of wits and will between American psychiatrist Douglas Kelley (Rami Malek, No Time to Die) and Nazi Reich Marshal Hermann Göring (Russell Crowe, Boy Erased), the former enlisted by the U.S. Army to help its leaders understand how to best confront the latter in court. Though there is a lot of additional material addressed in the movie (which clocks in at a healthy 148 minutes), at its core it is a mental pas de deux, where one man attempts to fool the other and vice versa. Along the way, everyone discovers the horrors of the Holocaust.

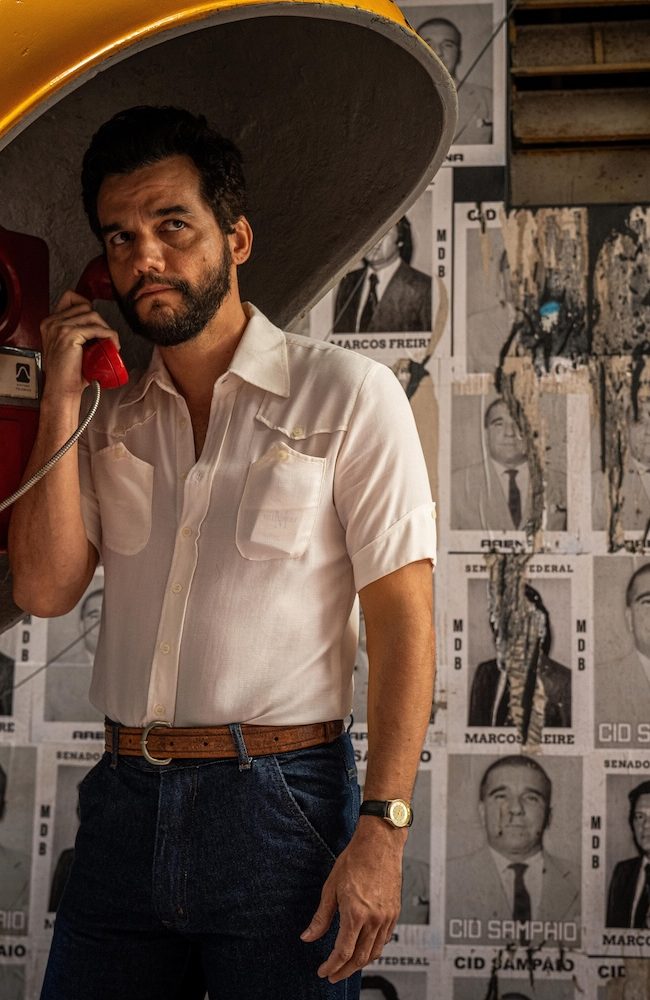

Nuremberg can be soggy in its pacing, with a good deal of actorly posturing from its stars; additional actors include Richard E. Grant (Can You Ever Forgive Me?), Michael Shannon (The End), and John Slattery (Confess, Fletch), plus an excellent Leo Woodall (Cherry). It sometimes feels as if Malek chose the role primarily for the wardrobe, so stylish is Kelley to the extreme. In other moments, we hold our breath at the ineptitude and lack of professionalism of certain characters, wondering how much chaos is sown for dramatic purposes, throwing obstacles hither and thither in order for the ultimate success to prove that much more meaningful.

And yet, Nuremberg may just be one of the most important films of this season, if only for its timely reminder that criminals—even if their actions are justified by the regime in power—can be brought to justice. “Following orders,” a common refrain among Nazis, is not an excuse. Dictators fall, new governments rise, and, as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. liked to remind us, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Fascists beware.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)

Sony Pictures Classics; James Vanderbilt; Nuremberg movie review