MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG

(Check out Brandon Wilson’s Merrily We Roll Along movie review, it opens Friday, November 5. Seen it? Join the conversation with HtN on our Letterboxd Page.)

There are few words in all of filmdom that strike fear in the hearts of cinephiles like the words “filmed theater.” Is it a general antipathy to filmed performance? No. Clearly the concert film has its adherents and films of standup comedians do not cause a strong reaction in anyone. But inferring that a film is essentially filmed theater is one of the most withering critiques you can issue.

And if a film has theatrical roots, there’s no escaping the opprobrium. If you film it like a play, that’s not good. And if you move scenes to other locations, (“opening up” the play, they call it) critics are likely to dismiss that as a failed attempt to get away from the story’s theatricality. It’s a no-win situation.

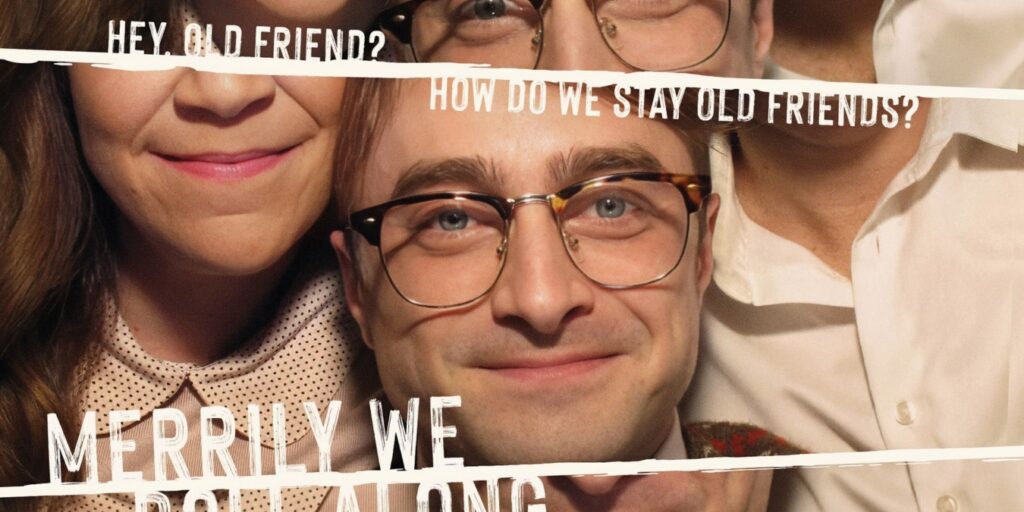

Director Maria Friedman has come up with a novel approach to the perceived problem with filming plays. She has made a film based on her smash revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along. In 1981, the musical was a notorious flop. But the musical, based on a 1934 play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart, refused to die. With music and lyrics by Sondheim and a book by George Furth, the ambitious musical charts 20 years in the lives of three friends: composer Franklin Shepard (played by Jonathan Groff), lyricist Charley Kringas (played by Daniel Radcliffe), and novelist-turned-critic Mary Flynn (played by Lindsay Mendez). Sondheim and Furth preserve a key device from the original play: the story of these friends starts when they are 40 and then works its way back 20 years. So in the beginning of the play, we are introduced to a trio rent asunder by personal and artistic betrayal, disillusionment, and heartbreak. And with each scene, we jump back a few years and slowly see how they arrived at their lamentable destination.

Friedman has eschewed the performance documentary approach. We do not see the theater, or the audience, though a title card lists the Hudson Theatre and a date in June of 2024, weeks before the triumphant show closed. Friedman has teamed up with cinematographer Sam Levy and film editor Spencer Averick. Averick is best known for his collaboration with Ava DuVernay (which goes back to her first feature length effort, the 2008 documentary This is the Life). Levy has worked with Kelly Reichardt, three times with Noah Baumbach, and shot Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird (which coincidentally featured a high school production of Merrily We Roll Along).

It is unclear to these eyes whether or not Levy is using film or digital video, and it frankly doesn’t matter. More importantly, the film does not have the digital sharpness one associates with other recent filmed plays (like the Hamilton on Disney+). Without sacrificing color saturation, the film has a grainer, grittier look that suggests film (even if it isn’t film).

Averick’s editing is sure to cause some consternation. Friedman frames the first scene, a Bel Air mansion party celebrating the newest film produced by Franklin Shepard, in a series of very tight close ups. The pace of the editing is fast. Unsettlingly so. This is not bad filmmaking. This is deliberate. Because Franklin’s triumph is actually his surrender to damnation. He has sold out and he knows it. His self-disgust is palpable. The film’s style reflects his inner turmoil. He has already lost the friendship of the idealistic Charley, and Mary watches him make the rounds at his party. She offers cynical, embittered commentary, like a sarcastic Jiminy Crickett.

As the play progresses and the story regresses, the style will change. There will be fewer close ups, more wide shots, less cutting. But Friedman loves to place Levy’s camera on the stage, sometimes moving the camera like a member of the ensemble. The result is quite original and very successful. It should be noted that often a film director is brought in to film a show like this, but Friedman (who once played Mary in 1992 and directed this production Off-Broadway in 2022 before moving it back to Broadway for the first time since its 1981 debut, in 2023) didn’t do that. This is her vision and she has done something truly original. She isn’t hiding from the theatricality, but her use of close-ups and editing has the ebullience of a theater director reveling in how film form can change a work. She makes something unapologetically theatrical and simultaneously cinematic.

I have avoided critiquing the show itself because better critics than I have already done that. But let it suffice to say that it is a marvel. Sondheim’s songs have a way of capturing you and not letting go. I have been listening to the cast recording repeatedly since I saw the film. Furth’s dialogue is witty and he makes great use of our chronologically reversed perspective. The show captures the road to middle age perfectly. There are no heroes or villains here. Just people making choices, choices that seem reasonable at the time, even when in retrospect we know they will be disastrous. I am only a few years into my Sondheim era, I have seen 3 of his major shows on stage, but I am pretty certain Merrily We Roll Along is his masterpiece.

By the time we get to the final scene, which shows how Franklin and Charley meet Mary when they are all about 20, your heart breaks over their youthful optimism and hunger for a future that will realize their dreams but also take a terrible spiritual toll.

The cast is uniformly excellent. Groff seems to have been genetically engineered for musical theater. Radcliffe manages to convey his love for his friend even when he has to play the scold. Seeing Mendez go from an embittered middle aged alcoholic to a starry eyed college girl struck by love at first sight is astonishing.

When it comes to musical theater, we often compare Bob Fosse to Federico Fellini, for obvious reasons. But in many ways Sondheim and Furth’s musical addresses Fellini’s major theme with greater nuance: that fame has become for us what the church once was, and in the process it has made modern life a kind of hell. That’s where we meet Franklin, living “the sweet life” like Mastroianni’s Marcello at the end of La Dolce Vita. Sondheim and Furth show us how mass media and the siren song of fame lure us to our doom.

Richard Linklater is making his own film of this musical. But because he is shooting it over a 20 year span of time, we will not see it until about 2040 (Beanie Feldstein’s Julie played Mary Flynn in Lady Bird and she will play the same part for Linklater for the next 15 years). I look forward to that film, but I am grateful that someone preserved this production, which won 4 Tonys last year including Best Revival of a Musical, for those of us who cannot make it to the Great White Way. Friedman has proven that “filmed theater” in bold and assured hands, can benefit from the best of each artform.

– Brandon D. Wilson (@GeniusBastard)

Maria Friedman; Merrily We Roll Along movie review