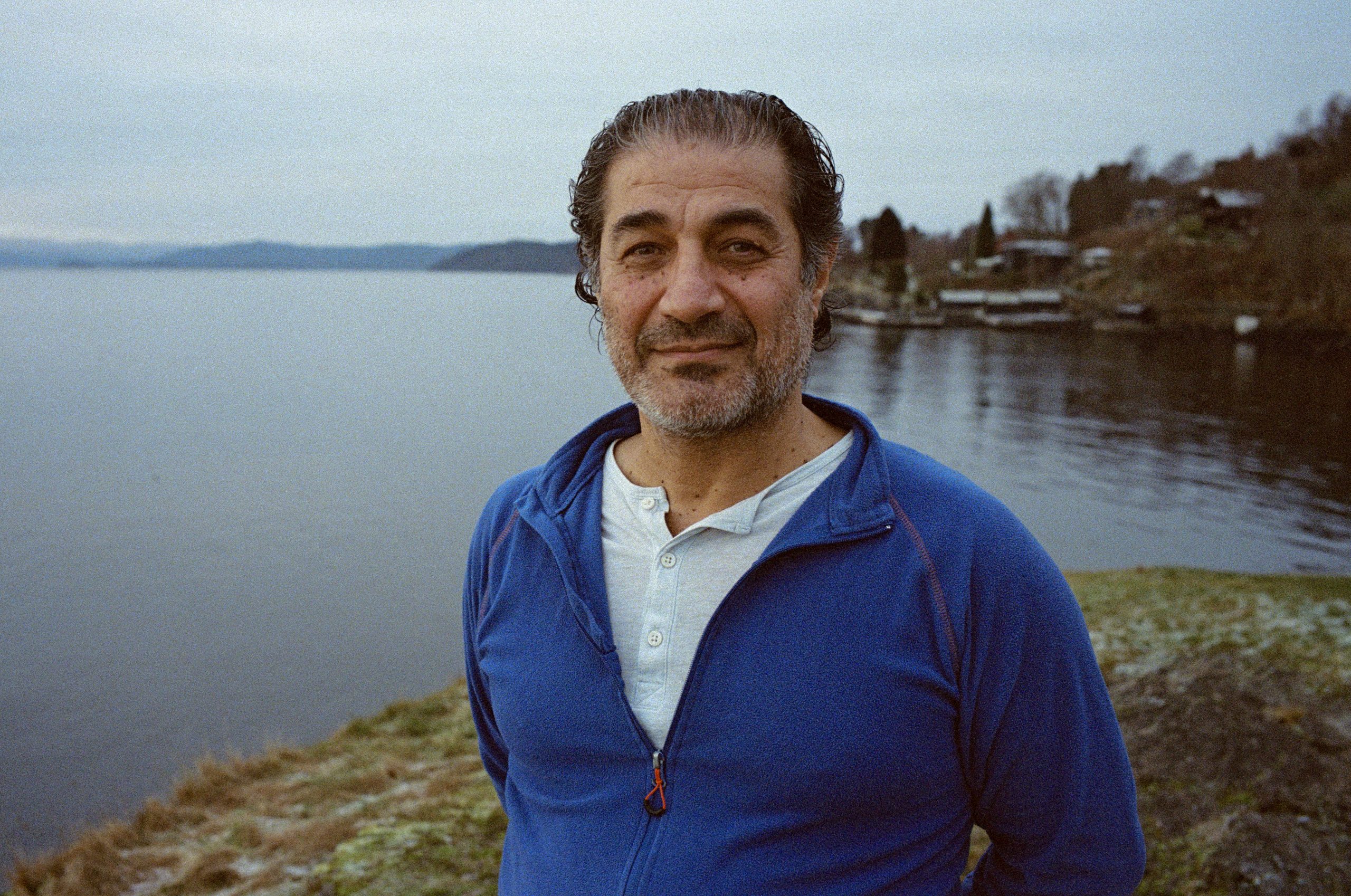

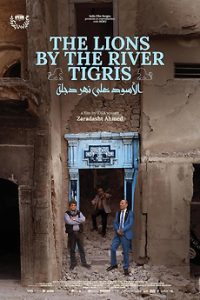

A Conversation with Zaradasht Ahmed (THE LIONS BY THE RIVER TIGRIS)

In 2017, after three years under the control of the Islamic State (ISIS), the people of Mosul, Iraq fought to reclaim their city. The nine-month battle to liberate Mosul was marked by catastrophic violence, especially in the historic Old City. Once home to more than 2,5000 years of history, the district was left largely in ruins. From the mountains of rubble, two stone lions watched over the wreckage. Carved into the surviving frame of a doorway, they marked the entrance to a house that no longer stood.

In his documentary The Lions by the River Tigris, Kurdish-Norwegian Zaradasht Ahmed follows two men whose lives intersect around this doorway. Bashar, it’s owner, hopes to rebuild his family home and the memories it held. Fakhri, an antique collector, seeks to preserve Mosul’s heritage, in part by attempting to acquire the doorway for safeguarding. While their goals put them at odds, both men are driven by a shared desire not only to rebuild, but to revive the city and its spirit.

The Lions by the River Tigris held its North American premiere at DOC NYC on November 15, 2025. In the following conversation, edited for length and clarity, Ahmed reflects on his return to Iraq, the stories he encountered there, and why the Lions became the heart of his film.

Hammer to Nail: While you’re originally from Iraq, you’ve been living in Norway for three decades now. What led you back home to make this film?

Zaradasht Ahmed: I was in Iraq, working on my other film, Nowhere to Hide, when the Mosul city fell. I went back in 2020; that was some time after the liberation. And the reason I went back was, I was looking for something else to make. I was connected to the invasion back in 2003 by the Americans. When the Americans took over Baghdad, all the museums, including the National Museum, which had tens of thousands of items, were looted. And then in 2014, nearly 10 years after the looting of the National Museum in Baghdad, ISIS also destroyed and looted the Museum of Mosul. Both incidents had been very traumatic for the whole world, so I wanted to make a film about that.

My fixer stopped the car in the old city of Mosul, and for me, that was really a shock, seeing that the place was carpet bombed during the liberation of Mosul in 2017. The devastation was so enormous, but why don’t we know about that? This old city, Mosul, is a kind of a living museum, and we [knew] little about what actually happened in the city. So that’s how the film started: I started to focus on the Old City, and then found this house with the lions, and then found the family, and then found the other characters.

HtN: How did you come to find these characters?

ZA.: Yeah, I found the owner of the house, which is Bashar. He’s the main character, but topics like this need some other characters to carry the film and also to widen the perspective of the city, because this wasn’t that house alone, it was the whole city. So I was introduced to Mr. Fadel, the musician, and when I met him, he had with him the this well-dressed guy Fakhri holding this amplifier. That was like a surrealistic scene, someone well-dressed and chic with all this rubble around. Soon later, Fakhri invited me to his home, where I could see the whole story of those three years after ISIS: the rise of the city, the cultural vibe, and the flourishing of the people back to normal life after ISIS. His house became a private museum, every inch of it. It was interesting to include some of the people that were very active in doing something about the post-ISIS time.

HtN: Your last film, Nowhere to Hide also takes a look into the effects of the rise of ISIS, following a medic in Iraq’s “Triangle of Death,” or the Diyala Province. In this film, audiences watch the brutalities of war as they happen. In this film, however, we only witness the aftermath. Why did you chose to withhold depictions of war in action?

A still from THE LIONS BY THE RIVER TIGRIS

ZA: I started with this film during Covid. So there was no Ukraine, no Gaza, no Lebanon, no Sudan, Armenia, you name it. All these wars that came later on. So I was ready to make a film about the brutality of ISIS. Then the Ukraine war broke. Things changed, seeing the brutality of Russia invading Ukraine, and then the whole world starts reacting to that. Then Gaza came in, 2023 while I was in the middle of the film; doing a film about destroying a city and the brutality. And then here you go, live on TV, its happening right in front of you. So after a lot of discussing with the editor, discussing with the producer, discussing with myself, [we decided] it wasn’t so interesting making a film about the brutality of ISIS. There are other ways of telling stories about war, indirectly. I realized the film could tell also the same story, even stronger, through characters like Bashar and Fakhri and Fadil that you like, that you care about

And for me, being in Iraq previously with the other film and experiencing these traumas with the main character there, every day you wake up, you say, God, please don’t let anything happen. This brutality in the material there, it does something to me. It’s traumatizing. But of course, my traumatization cannot be compared to those who live there, like with Louis, the main character of Nowhere to Hide. So I wanted something different.

HtN: There are a number of shots that focus on nature: birds making a home in rubble, stay dogs wandering throughout the destruction, grass growing amidst the rubble of Bashar’s house, and of course the title, emphasizing the river Tigris. What was your intent in emphasizing nature; what do these shots say about the relationship between humans and nature?

ZA: Nature sends messages, with the grass growing in the house, that the house is not dead. At the beginning of the film, Bashar’s wife says the house is like a dead person and to forget it. Nature sends messages, with the grass growing in the house, that the house is not dead. With the grass, with these birds, with these things, it’s the beauty of life that the heart is still beating there. It’s life; it’s life in itself. But it’s also connected to the river, because it’s the source of life, like for animals like the buffalo, the fish. It’s the great Tigris. The Tigris is in the Bible, and in Quran, and it’s the symbol of Mesopotamia. It’s the heart of life in that area.

HtN: In the film, Fakhri is taking on the incredible feat of preserving history after it’s been destroyed, and by capturing their stories through this film, you are also preserving Mosul’s story as well. What responsibilities did you take on in this effort to document and preserve?

ZA: One of the reasons I stayed on this [subject] was the shock I got from the Old City in Mosul, this 4000, 5000 year-old city being destroyed. These landmarks have been there since they’ve been built, but ISIS is coming here, destroying them. But we are there, and we are documenting it. In a world of TV, it’s not enough, because the news are not so objective as they’ve been saying to us. They twist reality, they twist the truth. So, in the film, I avoided focusing on the demonizing of ISIS, we just see what they do by the things they’ve been filming. So nothing subjective about that, it’s as objective as possible. I’m a journalist, so I have to be very factual. I have to be very balanced. There many quality checks and that information out there, all the pictures or whatever has to do with the archive have to be correct.

But it [the film] is more about the feeling of people that were affected, the feeling of people who stayed, the feeling of people who lost their things. This documentary is about humans, it’s about who we are; it’s also about being in a war zone, about post war cultures, cultures that are unknown to us, people that we never met. My camera is my tool to make less [of a gap], and more understanding. For example, you’re from America and I’m from Iraq; we have two different perspective of seeing things. America invaded Iraq and caused a lot of damage to Iraq, so it will be different perspectives, but we are all on the same planet.

HtN: You mention objectivity. Much of this film is shot in a very objective, vérité style, except for one moment, when Bashar, out of anger, begins to throw rocks at a looter. Can you place me into that moment what that experience was like and what prompted you to step outside of the vérité limits for a moment?

ZA: It was very scary for him, the guy. So the camera is picking up him, so I’m looking at him, but then I see [Bashar] throwing the rock, and then went to throw a second rock. If I didn’t move him, he would have hit the guy’s head. And then the guy started to react; he wanted to throw rocks at us. So it was just an immediate reaction. You never turn off the camera, but also you don’t cause harm. Rules are made to stick to, but it also depends on what you are doing. You can break them from time to time, especially when it’s about the security and the safety of those people who are involved. There’s there’s no justification there; you cannot wait for the eagle to eat the kid because you want to be observational, you have to interfere. So, it was breaking the rule of being fully observational and cinema verite, but nothing is more valuable than a human life. When you work in these hostile places, if you see something, you have to interfere.

HtN: Have you maintained a relationship with the characters from this film, Bashar and Fakhri?

ZA: Of course I spent a lot of time with them – and with the characters in my other film – so I always keep [in touch], but I don’t push it. From time to time, I update them about where we are, what we are doing with the film. And especially with Bashar, I’m collecting money for him, I’m trying to save the lions and help him to restore the house. We have collected some money, on this app called ShareDoc; maybe if we have $10,000 $15,000, it will make a huge difference for him.

– Kaitlyn Hardy