A Conversation with Scott Cummings (REALM OF SATAN)

“Hey, this isn’t Ken Burns” – Scott Cummings on Realm of Satan

The feature-length directorial debut of veteran editor Scott Cummings, Realm of Satan (reviewed here by Chris Reed), is equal parts visually stunning and (no pun intended) wickedly funny. Not to mention remarkably different from Penny Lane’s Hail Satan?, the last US indie filmmaker-Satanist collaboration to premiere at Sundance (an observation screaming to be coopted by the Christian right).

Politics-free and artistically rendered, Realm of Satan is basically a meticulously framed series of strange staged tableaus – from Satanists face-painting, to communally worshiping, to mundanely hanging laundry. (And also my hands down favorite, simply standing beside a lawn sign touting a reward for the arrest of the arsonist that torched the Church’s headquarters – to the tune of $6,660.) It’s all the oddball result of the director behind Buffalo Juggalos – Cummings’s first experimental nonfiction/fiction dive into a much-maligned band of outsiders – having spent 7 years getting to know the various members, including current leaders, of the Church of Satan as intimately as any nonbeliever might. (And for those nonbelievers who can’t keep your Satanists straight, I should clarify that the Church of Satan is Anton LaVey’s creation – not The Satanic Temple of Lane’s 2019 doc. That said, the grassroots political activist pranksters Lane portrayed do seem to share a similar penchant for approaching life with a theatrical wink.)

Hammer to Nail: Your award-winning Buffalo Juggalos came out a decade ago, and likewise explored a “sinister subculture.” So what draws you to subjects with, as you put it in your director’s statement, “cultural baggage and cache?”

Scott Cummings: I love fiction films with nonprofessional actors in them; when you watch Andrea Arnold’s Fish Tank you feel the star Katie Jarvis has a personal history that informs the whole film, and the line between the character and the performer is unclear.

That’s what I was initially looking for with the Juggalos – people who had stories that you could feel by looking at them. But then I realized there was something else interesting – another layer. Just by knowing they are Juggalos the viewer’s imagination is triggered. The film becomes about the viewer’s expectations and fantasies because the viewer has ideas that are being both confirmed, refuted, and turned on their head. That cultural baggage brings this other layer and allows you to have a bit of fun with the viewer (or even at the viewer’s expense).

Revisiting this with Realm of Satan, I thought about their reputations for being both sinister and mysterious. So that starts to inform the viewer – the viewer assumes they practice black magic, they’re carnal/sexual, they’re sophisticated, they burn down churches (which of course is not true), etc. And I tried to use that to the film’s advantage, and also to allow the viewer’s imagination to get to work.

Beyond that, the word “Satan” is a powerful magic word; it causes an immediate response in the listener. “Satanist” does a huge amount of work even before the film starts. It charges the experience and automatically opens it up as magical.

HtN: I was surprised to learn that you bonded almost immediately with High Priest Peter Gilmore due to your shared love of certain films, notably Aleksei German’s sci-fi epic Hard to Be a God. So did you and your collaborators explicitly reference specific movies as you were developing the look and feel of the film?

SC: The main thing I always wanted to drive home with everyone in the film is that this is not a documentary, but something else. We’re making cinema together – our own thing.

So I sent my previous film Buffalo Juggalos to everyone as a reference. I also sent them my pitch book, which had a bunch of references from, like, Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life. I tried to keep it clear, “Hey, this isn’t Ken Burns.” Peter and my friend Charles, who is the first Satanist I met, are both pretty serious cinephiles; they’d recommend things to me – like Blood and Black Lace or Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula, or lots of Hammer and Universal horror films. The visual FX stuff really started sneaking in because of that.

I guess the really big one was Peter kind of redirecting me back to Ken Russell, who was one of my early favorites but who I’d kind of forgotten about. One of the Satanists, Adam Cardone, is a stage magician, and he directed me toward David Copperfield’s TV specials. They are often done in one long take because a modern audience won’t be deceived by editing tricks – the camera works with Copperfield to enhance the illusion. What a revelation! Film schools should show Copperfield’s Great Wall of China episode.

But my main references for everything always includes Freaks, which is a film that is very dear to Satanists. I can’t tell you all the details, but it seems that the rediscovery of Freaks came about in part because Anton LaVey recommended it to the San Francisco Film Society. Freaks had been maligned for decades, and LaVey was a big part of its revival. Freaks is really a touchstone for everyone in front of and behind the camera. (I’ll add that High Priestess Peggy Nadramia is writing an article about LaVey and Freaks, so look out for that.)

HtN: The credits list a few dozen participants, making note of who isn’t a Satanist, which made me wonder how you cast all these characters and whether there was some sort of criteria for getting involved in the project. Did you meet everyone through Peter or through word of mouth? Did you put out an open call to Satanists?

SC: I met a bunch of people early, on my own, and then just kind of lurked around Reddit and Facebook seeing who knew who. A big part of my process is Facebook-stalking, following chats. Beyond that, Peter directed me to people he thought were interesting and would be amenable to such a crazy project; and then, because I think those people really had a nice time shooting with us, word of mouth also helped. I’m appreciative that so many people vouched for us.

Initially I wanted only Satanists in the film, but a lot of the non-Satanists (all of them fellow travelers) are connected, mostly through serious significant others. There is also a drag house that appears – their house mother is a Satanist and what she says goes. They’re all pretty witchy, though.

HtN: This film had a lengthy gestation period, as you immersed yourself in the world of Satanism for seven years before the (60-day-plus) production began. Why did it take this long? Was a slow methodical process part of the plan?

SC: No, it was not part of the plan – it was a fraught process. The first step was getting money for the film, which took a long time, but thankfully we found a great partner in Asterlight. We tried fundraising in Europe, and by 2019 had things quite together with our American funder and a European producer I was very excited about. We then prepared to bring our DP Gerald (Kerkletz) to the US in April 2020 to start shooting.

And then…Covid. So the idea of making a film that involved going into the homes of a bunch of pseudo-strangers and working face-to-face with them was out. I had a moment of wondering if it would ever be possible to film anything ever again. Not just me – I was worried the whole film industry would collapse. So I just kept reading the books, chatting with people, just tried to get by.

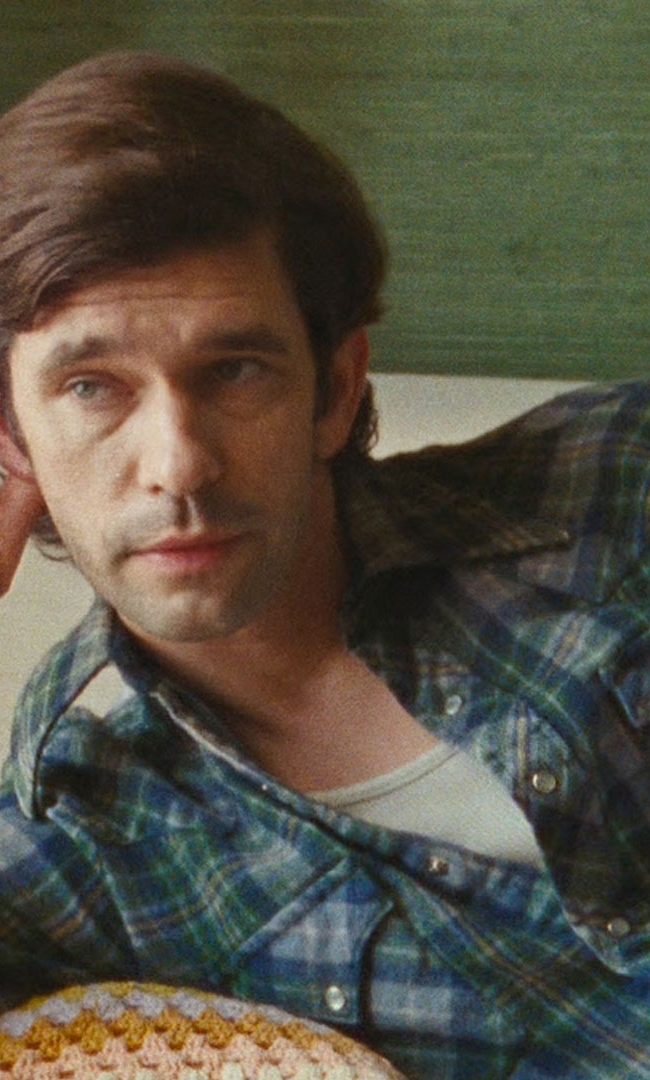

A still from REALM OF SATAN

Thankfully, our financier stuck by us. (Though for practical reasons we didn’t continue on with our European producing partners. Hopefully we will with the next one!) Caitlin (Mae Burke) and I also took a little detour to make a short for Field of Vision in the midst of the process. I love their work and couldn’t not do that.

As far as shooting, we did, like, two to three shots a day maximum. We’d spend all day getting one shot. That’s a gift afforded by a very small crew. I worked with a truly outstanding cinematographer who never complained once because, honestly, it was a bit of luxury that most small films don’t have – we could take our time.

HtN: Though this is your first feature-length directorial debut you’re also a veteran editor who’s worked on many acclaimed indies (Benh Zeitlin’s Wendy, Eliza Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always, Reinaldo Marcus Green’s Monsters and Men, etc.) So how has editing fiction films influenced your approach to your own nonfiction work?

SC: Ultimately, narrative and fiction is the basis of everything I do. I think editing has really given me a way to find or create a sense of narrative or forward movement, and also strategies for how to seed things to give that feeling. That is of course very useful; I purposely resist too much narrative with Realm of Satan, but there are elements that you can follow if you want. Some you may need to watch more than once to find.

The film that opened up the most possibilities for me with this project was probably Benh Zeitlin’s Wendy. It was a long process in the room with Benh, with a huge amount of digging into the footage and impossible problem-solving; and that was the first film I worked on with serious visual FX, largely practical. Of course, like Benh I’m not super interested in CGI spectacles, but the idea of simple VFX was really really appealing to me, especially doing it in a hands-on way.

– Lauren Wissot