A Conversation with Owen Kline (FUNNY PAGES)

Three years ago, at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival Directors’ Fortnight, I had the opportunity to speak with filmmaker Owen Kline to discuss his remarkable feature directorial debut, Funny Pages. At the time, Kline was most notable for his memorable performance as the younger son in Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale, however, with Funny Pages he established himself as a distinctive voice behind the camera.

Funny Pages, which A24 would go on to distribute, is what Kline describes as “a regressive coming-of-age story.” The film follows Robert, a teenage cartoonist played by Daniel Zolghadri, who rejects his comfortable suburban Princeton life in a quest for artistic authenticity. Shot on 16mm film, the movie captures the gritty texture of New Jersey’s comic book shops and working-class neighborhoods, while exploring the complicated relationship between a young aspiring artist and Wallace, a cranky former comics industry worker played by Matthew Maher.

Recently, Owen has been back in the spotlight, appearing in episode 5 of Seth Rogen’s new series The Studio. But back in 2022, speaking in Cannes after the film’s Directors’ Fortnight premiere, we talked about everything from his obsession with 16mm film and underground comics to his four-year editing process and his collaboration with the Safdie brothers. The following conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: So in 2013, 2014 and 2016, you released the films Foul Play, Jazzy for Joe and Steve Dalachinsky. Now in 2022, you’re here with your excellent feature debut, Funny Pages. When did you get the idea that you wanted to start making films?

Owen Kline: I guess I always, like any kid, picked up a camcorder pretty early and was just messing around for years. But I always just kind of did that and drew comics at the same time. I never found any way to monetize it besides video editing. I was committed to just making these no-budget shorts in college and a little outside of college and was pretty focused on trying to find a voice within that.

I always had it in my head; probably it was The Squid and the Whale that cemented the idea that I wanted to maybe make movies just from being on a set and the nature of that set being a small personal 16-millimeter semi-autobiographical piece of work.

HTN: On each of the films you’ve released, you’ve served as the editor. Talk about the editing process for this film and why editing is so important to you.

OK: Editing is the final authorship of a film. You’re a writer and a director and you’re trying to enhance everybody’s work. It’s hard to talk about editing in an original way, but for me, that stage is where a film ultimately finds its voice or where its voice comes together.

The earliest stuff I made, technology-wise, I was lucky enough, it was in-camera editing first and then VCR to VCR off a weird, cheap plug-in monitor, camera kind of situation. Then around my early teens, the first version of iMovie came onto the Macintosh or whatever. I think it was on the Gooseneck, remember that? Not everybody grew up with non-linear editing systems.

Having that at my fingertips at that age, transitioning from that to Final Cut Pro 7 to Adobe Premiere, really benefited me to have editing as a part of the toolkit as early as filmmaking. I think it did for most kids my generation.

In terms of the process of this movie, it was an ever-growing thing for many years where it was a very mercurial process, mostly due to me. My process is just very mercurial with material. I found I kind of stumbled my way into some sort of backwards process with short films. I went to Pratt, which was an art school and film school. So they just had equipment, old equipment laying around. People were kind of flocking to the DSLRs at the time, which were new. It was sort of just transitioning from HDV to the Sim card and then they had all these NPRs and they had a giant Steenbeck laying around and people were just at the computer lab. There was this other room where it was just littered with bags of Doritos on the floor, it was my office. It was just this nasty office with the weird stuff I was making and nobody used it except me.

I always just edit and edit. The shortest part of the process is the shooting. So you plan and plan and plan with the writing, and then you shoot, and then you edit and edit and edit.

HTN: How long was the shooting process for Funny Pages?

OK: Like 30 days and then four years of editing. Within that four years, a couple of different other moments that we tried when we were able to get a little bit of money. It was just the kind of thing where I kept pulling it apart and moving things around and finding it organically within that. And then in doing that, you pull out one thing and you go, “That doesn’t feel like something the character would actually do now that I’m seeing it on film.” It worked for 400 drafts, but it didn’t work when I saw it. All of those drafts that I did, I never vetted that idea properly and the character would not say or do that. So it either gets cut out or replaced with another scene. I was just constantly kind of sawing these things in half, like a David Copperfield trick, and trying to figure out what to stick in the middle to make it work. I just feel like everything is kind of falling apart at the seams constantly.

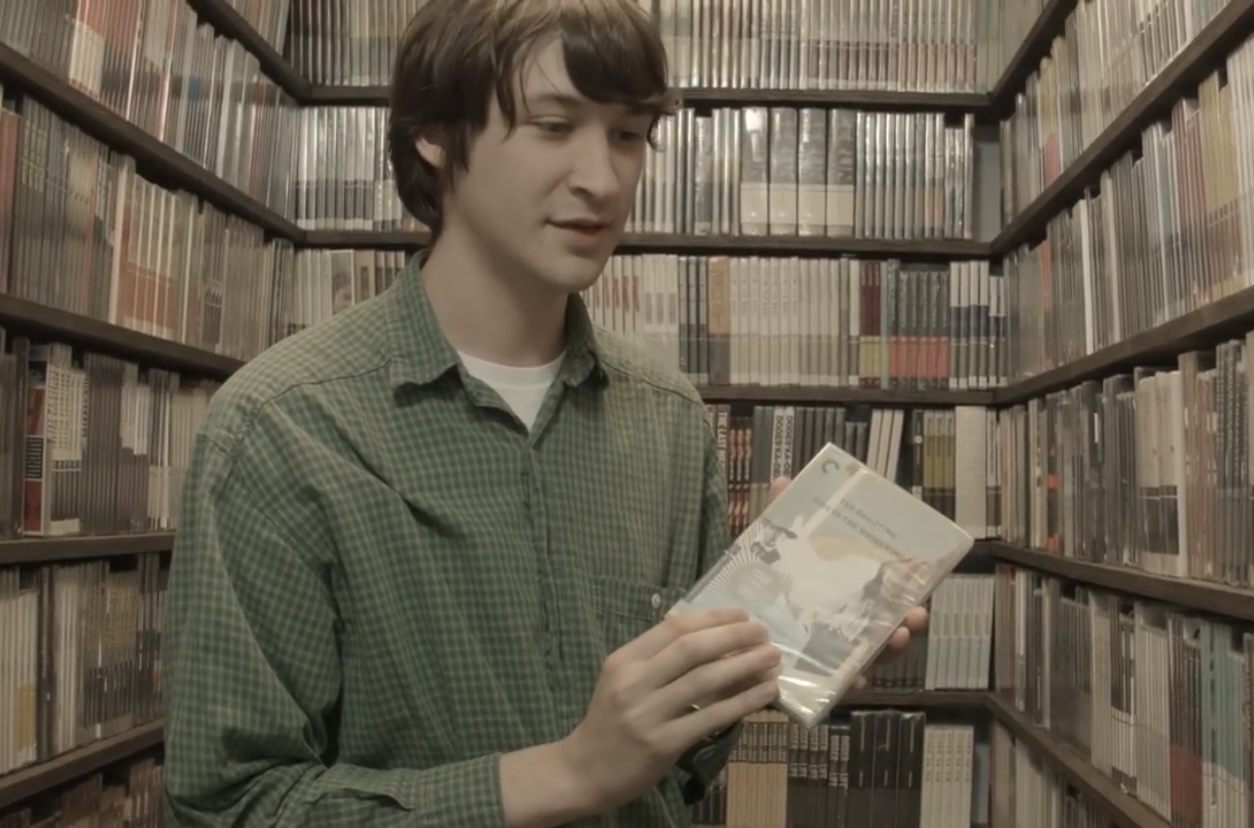

A still from FUNNY PAGES

HTN: You said there are lots of drafts. The film clocks in around 86 minutes. Was there a longer or even shorter iteration of this film?

OK: Yeah, longer. The original script of this movie from 2014 was probably a hundred pages. And it remained around that number for just under 200 drafts. I know that number because I was able to count the Tupperware that I saved every draft in. So I know it’s under 200, but it’s between like 120 and 200. I lost track somewhere.

Sometimes it’s just a character sweep. Once in a while you’re just looking at it and you go, “This character is just not working. I need to think about this character more in his world and what he’s saying and how to incorporate him better.” Just thinking about Cheryl’s (Marcia DeBonis) purpose, the defense attorney, and how you can best utilize her with every piece of real estate.

HTN: Was it always a film or is there a comic book iteration of this story that you conceived of?

OK: There was a kind of proto version of the first scene where he enters and tours the boiler room, called Robert in the Boiler Room that I did as a comic 10 or 15 years ago, I can’t remember. But it’s just in some little publication that I put out. I had forgotten that was even the first scene of the movie that I had written, because I just translated it over. It felt like something tonally that was specifically kind of visual and for a comic. I thought, “Well, maybe this grammar will translate by virtue of the fact that it was designed for a comic.” So I think it was significant. It was like a significant piece of silly putty to sort of stick before adding more.

HTN: The film is shot on 16mm. Talk about the decision to shoot this on film and why 16mm over any other format.

OK: As a teenager, I was just obsessed with 16mm and I worked at Anthology Film Archives on different things. I was an intern there and then helped this guy Andy Lamper. We worked on a lot of projects together over the years. He would let me raid the Anthology basement because he was the archivist.

The Anthology basement was just full of anything that was donated to Anthology on 16 mm, 35mm that didn’t have any value or use to the archive. It was bad 16mm , badly timed dupe prints, 16 dupe prints of like March of the Wooden Soldiers with Laurel and Hardy, or like a bad Canadian educational film about how your clothing can burn, or like a clip from Beast of 20,000 Fathoms that they distributed to play in front of stuff in cheap 16 theaters that would run 16, or just strange things that I would pick up. Anything that was trash to them. But putting it through my school’s Bell and Howell library projector and unearthing it was just very exciting as a teenager that was mostly staying away from drugs.

The reason why we shot 16 was that it felt right for the palette, it just felt right for the movie. And it was rich. It’s funny, because a huge reason was because I wanted a lot of fluorescent light in the movie. And fluorescent light looks wrong. It kind of looks like those sterile science fiction movies when you have fluorescent light on digital. It reads in a different way on 16, that yellowing light and flicker reads in a different way on film. But then ironically, the movie is actually pretty colorful in the end. It doesn’t really have that drab fluorescence. In the comic book shop, you have all this color and all this kind of Technicolor comic books everywhere, but it’s with this ugly yellowing light. And somehow those things interact in a way on film that they didn’t on video.

HTN: I’m a big fan of A24 films and I just want to know what the process of working with them was like? Were they involved in production or just distribution?

OK: What’s great about A24 is once I figured out the movie and had the movie, they were very cool about it. They got what the movie was and it was its own demented custom car.

There’s this car in Peter Bagge’s Hate, he buys this car and it’s like a monster truck car. It’s put together by his white trash neighbor, and it’s this funny, horrible car, but it’s a custom car. There’s nothing like it. It’s got this weird paint job on it and then these gigantic wheels and it rides high, but it’s this terrible car. But they let me build my terrible car and figure out how to run this terrible car. Then once it ran, they stepped in and really got behind it.

HTN: It’s like the Cucaracha. [the car in the film]

OK: Yeah, the Cucaracha. I stole that one from Josh Safdie’s car. He used to drive around in this white convertible that they nicknamed the Cucaracha. It was just one of those details where I just thought, ” I’m not gonna make up something like that because we have it and it’s real. It has more to it. It’s just gonna fit in an actor’s mouth better and feel real to us.” I’m glad that you caught that.

HTN: Speaking of the Safdie brothers, not only are you friends with them, you acted in their film John’s Gone in 2010. What was it like working with them and when did you approach them with this idea?

OK: Well, I met Josh when I was 15. I really liked his short films and he really liked some of the comics and short films that I was doing in high school. They were completely amateurish, but I think he saw raw talent in me and employed me a few times just to help make his little projects and see how it was done.

I realize now too, when I was like 15 or 16, we were running around New York. I remember getting kicked out of a Chinese food restaurant for sneaking this shot. the scene is they’re getting dinner and then they went inside the restaurant and had dinner and we shot through the glass of the restaurant. It was probably a more interesting shot in retrospect than if he had gotten the shot-reverse-shot at the table. It had that sort of “every film is a documentary” Godard quality of the fact that the devious decision to shoot it that way out of necessity provides a creative detail. Like the Cucaracha, it adds an extra layer of realism or atmosphere and personality.

I tried to stick the boom a little bit subtly and we were out the door. I guess that “just don’t ask permission” was the thing that I really learned from them. They’re the first people to really treat me seriously creatively. I animated a trailer to their first feature they did together, Daddy Longlegs.

I did all these different projects with them. Then acting with them and stepping into the universe was really fun. Those guys just always thought it was really funny when I was a teenager, I would go to flea markets and stuff, then I’d buy a couple of things and sell them right at the table to somebody else. I’d pick through and I’d find a rare early rock record on some label, and then someone would come over and be like, “Oh, that’s rare,” and I’m like, “Yeah, I just bought it from him. I’d give it to you for 20,” or something

Then I would go at the end of the day and make deals when people were trying to pack up and try to not bring some big giant picture of a chimpanzee for Kodak home. You just acquire a whole frightening realm of junk this way. They had this nickname for me, “The Junk Diver.” My name in that movie was Owen the Junk Diver. My friend Charlie Judkins, who’s a ragtime pianist and historian, is playing opposite me as my best friend. He really was my best friend in high school and continues to be.

In fact, it’s Charlie’s comic that is Miles’ comic in the movie. When we were teenagers, he put a monkey on his back. I go and I buy some rare speakers that Benny doesn’t realize are rare. I bought an illustration of a fake outsider artist named Bongo Joe. I ripped off Benny.

It was a really funny scenario. Just how they incorporated and sort of made me this shyster in the thing and kind of cartoonized me and Charlie and our outrageous interests as teenagers. That was another kind of seed or impetus; that was an early inkling towards this project in some regard.

Then they got involved. I spent a couple of years writing this thing and just trying to get anyone to even read it, period. It’s very difficult. Sometimes you can get a contact or something and all you can really get out of them is “We’ll read it,” and then they never read it. We’re just nice to you. So nobody could read it, nobody would read it. After like two years I was trying to make it better based on what people told me but people just didn’t get it. I wasn’t changing it around that much, but people just didn’t get it.

Josh got it. Josh read it and got it and stepped in and made it happen at a time where I was really ready to throw in the towel on it because it seemed fruitless to even get five bucks for this thing. No one actually wants to spend $15,000. What movie in the world nowadays is made for $15,000 in terms of profit? It’s very difficult to do that. Nobody wants to trust you for the first time too.

Josh had been through that. The way that Josh and Benny figured out their voice was just inundating themselves with making short films in college and just going and going and going and just treating everything like a film. So they sort of transitioned very seamlessly to making features by just sort of inundating themselves with filmmaking and doing it for nothing. So they were able to just pivot in this way where they didn’t have to think about it. They were less inhibited because of the feature process initially. I just love their work so much.

HTN: Unfortunately, I think we’ve run out of time, but really it was so nice to talk to you and I really do love the movie and I look forward to whatever you do next.

OK: Thank you so much. I really appreciate that. A pleasure to meet you.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)