A Conversation with Kleber Mendonça Filho (THE SECRET AGENT)

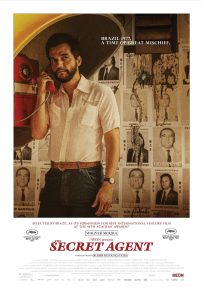

Winner of the Best Director and Best Actor awards at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival, The Secret Agent, from Brazilian director Kleber Mendonça Filho (Bacurau), takes place in 1977 during Brazil’s military dictatorship. It was a time of violence and corruption, and also an era during which Mendonça Filho was a child, and his memories inform the narrative. We follow main character Marcelo (Wagner Moura, Civil War) as he returns to his native Recife (whence Mendonça Filho also hails), unknowingly chased by hitmen for the crime of standing up for himself. While Marcelo pursues research into his family’s history, we cut back and forth between the past and present, modern-day journalists investigating the 1970s. It’s an often-harrowing look at a society that very much has resonances for us today. I had a chance to speak in person with Mendonça Filho at the recent Middleburg Film Festival (where I also reviewed the film), and here is that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: This film, as I read in the press notes, is pretty personal to you for a lot of reasons. You grew up in Recife and were a young child in 1977. I think we’re about the same age, you and I. And I imagine you like the boy we see in the movie. What do you specifically remember about this time now, as an adult?

Kleber Mendonça Filho: Well, as it often happens, I remember something very specific that happened in my family. My mother got sick; she had her first struggle with breast cancer. And at the time, my brother and I were kept very much in the dark about what was happening. My younger uncle, Ronaldo, took us away from home and to the cinema many times for about three months. And that really put a timestamp on ’77 and early ’78. I mean, I would go to the cinema with my mother all the time, but not so many times in such a short period of time.

And then I remember the downtown area very well: the sounds, the smells, the smell of gasoline and the bad engines and blue smoke, cigarette smoke, and the cinemas, the amazing number of people in each screening, because at the time we had seven wonderful movie palaces in the downtown area and they overflowed. They would get all the big films and it would always be packed anytime of the day. So all of that gave me almost like a muscle memory about that particular time.

And then I remember specific details, like I went to a school which was not a military school, but every Friday they would make us march like little soldiers. This is something which is ridiculous, remembering today, but it’s part of the military regime. And of course, when I dedicated seven years of my life to doing research for Pictures of Ghosts, which is my previous film—it’s on the Criterion Channel—that connected me to many of my childhood memories because I could see, in the archives, many of the things that I only remembered from the point of view of a child. And I felt that all of that gave me the right energy to sit down and write The Secret Agent.

And then of course all the other stuff comes from my own understanding of Brazilian history and archives and bits and pieces from the newspaper and stories that my parents and uncles told me, stories that we all know. The understanding that the 1979 Amnesty Law felt like a self-inflicted amnesia in the country. And all of that gave me the right opportunity to sit down and write The Secret Agent, which I always wanted to be a thriller set in the ‘70s, something that would be not only exciting and violent and suspenseful, but also something with a big heart.

Our Chris Reed and filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho

HtN: They say smells and sounds are among the most nostalgia-inducing elements. Speaking of research, you began your career as a film critic and journalist, so research is something that you’re quite familiar with and this film celebrates the work that journalists do and the importance of the public record. Brazil recently went through a political crisis and your country handled it much differently than the United States has handled its own. What role did the press play in this most recent crisis?

KMF: That’s one hell of a question. Well, first of all, I have to say that I’m also the son of a historian, so I grew up seeing my mom come home with a Panasonic tape recorder and she believed in the technique of oral history, of interviewing people, listening to them, and putting things together out of what they told her. And then I studied journalism and became a journalist. So I really think that journalists—the good ones—are historians.

About the Brazilian press, in the recent very dark times we went through, big media did, I think, a horrible job, and independent media did a brilliant job. Sometimes I think the US media is similar to Brazil, but I also think sometimes even elements in big media feel to me like independent media. I think much more is said and written in the US in big media than in Brazil. One example is people like Jimmy Kimmel. The things those guys say are not said by late-night talk-show hosts in Brazil. The things they say are usually said in small independent media in Brazil.

So I really believe that for a number of years, and in fact leading up to the final disaster, which was Bolsonaro being elected, big corporate media played a very important and very irresponsible part, mostly because they have always been against Lula [current Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] because Lula is classic left, even if his policies are brilliantly balanced, which makes some of my friends from the left say that he’s a neoliberal, with which I disagree. I just think he’s brilliant and he manages to do a balancing act to make it all work. But I think corporate media in Brazil, which belongs to six families who get together once a month, did a criminal job in terms of leading Brazil down the rabbit hole of Bolsonaro, until Bolsonarism became such an all-around embarrassment that slowly they began to report on what I call reality. And that’s when things began to change.

HtN: Well, let’s hope we have something similar happen here. Let’s talk about the actual production of the film. I think your cinematographer, Evgenia Alexandrova, did a great job. I just recently saw a French film that she did, The Balconettes.

KMF: It’s the film she did just before mine.

HtN: She’s a great DP [Director of Photography]. I know you shot with the Arri Alexa 35 and anamorphic Panavision lenses. What kinds of conversations did you have beyond that to come up with the look of the film?

KMF: I wanted to work with after she shot Heartless, which is a Brazilian film we produced, and I saw the final result and I said, “Alright, I think we can maybe work with her.” The first thing I asked in our first meeting is whether she would be alright with using old anamorphic Panavision lenses. And she took it as a challenge and she loved the idea. I told her that I have a problem—it’s a personal taste thing—with the look of contemporary films. I remember back in 2012, when I was at the CPH:DOX festival in Copenhagen, I was on a jury and I saw ten films.

Eight of them were the classic contemporary Alexa look. And they were all filmed in Europe or Japan or Canada, meaning they were shot with the same kind of light, usually summer light, soft light. And I thought there is something amazing about the democratization of the image in film because today anyone can get hold of an Alexa, from advertising for a city council to a huge production. And that didn’t happen in the past with Technicolor or Super Panavision. David Lean would do Super Panavision, but the city council would not do Super Panavision and Technicolor. But now we are getting the same kind of image everywhere.

HtN: Every film today can look generically amazing.

KMF: Yes! This is exactly what I’m trying to say. Generically amazing. Because one of the things you have to be careful of when you make a film is that making a film means following protocols. It’s almost—almost, not the same thing—like air travel. But when you follow protocols in air travel, it’s a brilliant thing because we’re all safe. I’m completely for using protocols in air travel. But when you go and follow protocols for filmmaking, you might end up with the same cake.

Image is critical in modern filmmaking. And I really wanted to try something else. And what she said as a young cinematographer is that the word on the street is that the old lenses are not perfect and they’re kind of fuzzy-looking. And I said, “Exactly – that’s what I want.” Because when we add the imperfection of the older lenses with the Alexa 35, which is super dense and is an amazing digital camera, the mix of both elements is really interesting for the film, plus with really good work on post-production with the grading.

By the way, I do not miss 35 mm. Even if I wanted to shoot in 35 mm, which I don’t, I’d have to send it out twice a week with somebody to Paris, which I think is eccentric. So she said that what I said made complete sense and we would try and look for something different for the film. And I’m very happy with the way it looks.

HtN: It’s surprising when you see it’s not shot on film because it really has that textural quality that we expect in film.

KMF: I have to say, we never tried to go for the fake film look. We went for an image that looked right and then maybe in a strange way it has a film look.

HtN: Was Jaws an important film to you as a kid? Because it certainly appears that it was from how you reference it in The Secret Agent.

KMF: Jaws was an important film to me, just like it is for the kid in the film, because I did not get to see Jaws until I was 14 years old, on VHS. But I think the impact of that film, which says a lot about Steven Spielberg, comes from the strong images. So the little bits and pieces I saw in a TV spot, on the poster, on the lobby cards outside the theater, really played with my imagination. And I remember when Jaws 2 came out, it had a similar impact because I remember the poster was this woman waterskiing in front of the shark.

A still from THE SECRET AGENT

HtN: Not as good a movie, though, as the first one.

KMF: Not as good, but not so terrible, actually. But of course the first Jaws is a masterpiece. And then the third one is despicable, and the fourth one is impossible.

HtN: Remind me, which one is “The Revenge”?

KMF: The fourth one.

HtN: That’s right. Except for the fact that it has Michael Caine in it, it’s otherwise ridiculous.

KMF: It’s a disaster. So it did play with my imagination. And then I remember I was a young swimmer in an Olympic-size swimming pool at the time, and I remember once I froze in the middle of the pool, terrified of just the idea of it.

HtN: So, Wagner Moura, your lead actor. Did you always know you wanted to work with him in this?

KMF: Yes. This is the first time I’ve written something specifically for an actor. I’ve known him for a number of years. I know his films, his work in theater and television, and I thought, let’s do something that he hasn’t quite done before because I really think he has charisma.

HtN: He does.

KMF: He has a film-star thing. The camera likes him. And I think he also has the quality of empathy; he generates empathy. I think of James Stewart or Cary Grant, in a way. You look at him and I think a lot about North by Northwest. It’s a very different tone, of course, but Cary Grant’s character in the film knows nothing about what’s happening around him. He’s always going from A to B, from B to C, from C to D. And I love that film because if you try to explain the plot of that film, good luck. So I think there are similarities between the two films. They’re different in tone, but similar in the way the character doesn’t really know the type of danger he is in.

HtN: I love that. Thank you so much for talking to me. I very much enjoyed the conversation.

KMF: Thank you.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)