A Conversation with Marialuisa Ernst (A PLACE OF ABSENCE)

During Argentina’s Dirty War between 1976 and 1983, up to 30,000 people disappeared. Many were dissidents and activists publicly opposing the military dictatorship, Proceso de Reorganización Nacional (National Reorganization Process), though others were citizens suspected of being “terrorists” for having leftist or socialist views, or advocates of social justice. Many of these kidnapped people were tortured and killed without any identification, leaving their families in a purgatory of hope that their loved ones were alive and grief for their probable loss.

On Thursday afternoons, thousands of anguished mothers and grandmothers gathered in Buenos Aires’ Plaza de Mayo, demanding answers to their children’s disappearances. Since the mid-1980s, human rights organizations such as the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP), the public, and law enforcement have uncovered numerous unmarked mass graves, discovering the remains of the lost men and women, finally bringing tragic closure to their families. One of the discovered men was filmmaker Marialuisa Ernst’s uncle.

Ernst’s film, A Place of Absence, unearths this tragic family history while acknowledging the disappearances that continue in South and Central America today. Just like the mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, today the Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants travel across Central America searching and begging for their children who have been lost, kidnapped, or disappeared on the treacherous journey to Mexico and the U.S. The film follows two of the mothers in the caravan, Leti (Leticia) and Anita, whose daughter and son, respectively, disappeared after leaving their homes. Tying in verité filmmaking, archival footage, stop motion animation, and performance art pieces, Ernst presents an affecting journey of grief, longing, and perseverance.

A Place of Absence had its world premiere at DOC NYC on November 15, 2025.

In a conversation with Ernst, edited for length and clarity, she shares the impact following the Caravan had on her own life and where the mothers are now.

Hammer to Nail: A Place of Absence intertwines two films into one: a film about the mothers of disappeared children, and a film about your family following the kidnapping and disappearance of your uncle. Much of this film is derived from your own life and family, but how did the mothers of missing migrants come into play?

Marialuisa Ernst: This story found me. We had found the remains of my uncle in a mass grave after 30 years. I traveled [to Argentina] with a camera. I had this incredible access to show this incredible thing. My mother was saying goodbye to her little brother and I had this incredible footage. I wanted to make a movie, but I wasn’t sure how it was going to work out because I had no funding. Some years past, I started researching the Desaparecidos in Latin America (the disappeared people in Latin America) and what it popped up was the mother’s caravan. I had no idea what this was and couldn’t really believe it at the beginning that there were so many disappeared migrants. But I contacted them, and they invited me to travel with them, just like that. I just grabbed a camera and a friend came along with me.

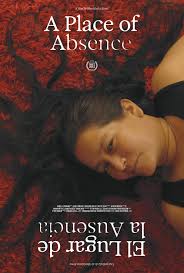

A still from A PLACE OF ABSENCE

We didn’t really know what we were getting into, but after we met them, ah! They are so incredible, their stories are amazing. It’s such an important thing to tell right now, what’s happening. And so I decided I’m going to make the movie of the mother’s caravan, then. So my first intention was to put a little bit about the Desaparecidos, but it became so big that I started sort of working towards this other movie. And it was somewhere in the middle that I realized that it is so interesting to talk about ambiguous loss. And then I start sort of putting the stories together.

HtN: How did making this film change your perception of yourself, your mother, and your family’s story?

M.E.: I could understand my mother probably went through a lot of pain in her life because of this experience. I experienced it too, but I never really understood it directly until I met the mothers of the caravan. They were so open and so vulnerable and really sincere. The way they expressed their grief and cried openly and expressed their feelings without any fear, I think it’s very empowering and I think it’s very brave of them. I don’t see that as a weakness, I see it as a bravery, to dare to show your emotions. The moment that they share their emotions, their emotions are seen, and they have a witness of their emotions, and they can see a mirror in the experience of each other and all the mothers of the caravan. Anita and Leticia became a little bit like a mirror of my mother, you know, like pseudo mothers. And it also helped me be sort of like a mirror. I had to put myself in the film for the film to work. It was not working until I put myself as sort of this person that tells the story, but very, very presently.

HtN: When did you decide to include yourself in the film?

M.E.: I always had myself a little, but mainly my voice. In 2020, I was ready to finish the film. I had edited the whole thing, it worked, it was a beautiful film, it was great. But there was something missing. I decided I was going to shoot a test of me doing these performance art pieces. I went with a friend and a really small camera into the forest and we made them and I ended up putting them into the film. Until the end, everybody was fighting me, that I shouldn’t do it, that it did not work. But [with the performance pieces], I was able draw lines and suggestions, so all the stories that were in the film and all the different subjects kind of became a more cinematic experience with the audiovisual language.

HtN: Could you share a bit about your background in performance art and how that medium translates to film?

M.E.: I came to this country, invited by the NYU to a conference of performance art. I love New York City and the state, so I got an artist visa, but I spent a few years of my life traveling and doing performance art. I knew it well, but I didn’t know how to translate it into something that is recorded. It felt like I was performing for the camera, but I didn’t want to perform for the camera, because that’s why I do documentaries. But I think documentary is such a free art and is similar to performance art in that way, because you can do anything you want, absolutely anything. Like, why not put myself in the film? It took a lot of discovery, a lot of trial and error to make this work within the film because it’s not something that I’ve seen in films. But I’m interested in pushing the boundaries of documentary, narrative, or even performance art – really art in general.

HtN: You mainly follow two mothers in the caravan, Leti and Anita. What about their stories stood out to you amongst all the women in the caravan?

M.E.: Oh, my God, it was so hard. I was following a few of them. I had finished editing a film with [another mother], but then Leticia called me, and told me that she had found her daughter alive. I was the second person that she gave the news to, so of course, she had to be the other person in my film. I tried to put stories of other women, but it didn’t work, because you really needed to connect with them and not just see them as stories passing by you. I wanted the audience to really dig deep into the experience of one or two of them. And Anita is such an amazing woman, so freaking powerful. She she was one of the founders of COFAMIDE (the parents of the Desaparecidos in El Salvador), she came on multiple caravans, she’s a speaker, and she helped a lot of other mothers in their pain and actually in finding other loved ones. She had to be there.

HtN: Mothers are subject to this stereotype that they are these docile, doting, even passive beings, and your film does a remarkable job of plainly demonstrating how untrue that idea is. Was counteracting this image of mothers something you kept in mind while filming?

M.E.: Well, my mother is a single mother. She studied while she had three little babies and then raised the three children by herself, so I definitely have seen the strength of women. I always believe women are so strong, but we are portrayed as not that strong, so I really wanted to capture this. Though, it’s not that I tried to capture it, it’s there, you just gotta open your eyes. Women in history everywhere are strong, the problem is that we’re not seeing with those eyes. In Argentina, the mothers of Plaza de Mayo could have been killed by the dictatorship, the authoritarian government, and they didn’t care, they peacefully protested every [Thursday]. And then the mother’s caravan, traveling thousands of miles, sleeping in migrant shelters on cement floors, following the steps of the children, literally, walking in the sun without eating really much food, and with what they do, they’ve been able to to create some change.

Before, when a Central American person disappeared in Mexico, the family members couldn’t do anything to tell authorities in Mexico, and there was not a way of doing it in their own home countries. They had to come all the way to Mexico, migrate as an undocumented person, and go to the police and say, “My son disappeared here, can you look for him?” But in all these years of maybe 15, 16 caravans already, they were able to change the laws, and now they can go to their own countries and start the process in their own homes.

HtN: Can you share any updates on how these mothers are doing and whether any more of them have found their children?

M.E.: Two weeks ago, Guadalupe died. It’s terrible. She never saw her son. She had a lot of medical [issues]; she told me she started getting sick when her son disappeared. A lot of these mothers have very serious medical [issues]. The sadness make them sick, like high blood pressure, diabetes, Leticia suffered a stroke when she found out that her daughter disappeared. So a lot of very heavy things happen to their their bodies.

Lillian, who is the one who was at the mass grave in Mexico and said, “What if my sister is here,” she lives in an island in El Salvador and she takes care of the two sons of her sister, the disappeared sister. She’s very humble, she works the land, she sells some things for tourists, she doesn’t have much money. A few years ago, she called me and she told me that both of her nephews had been told that they had to join one of the gangs of the island because they were of age, and if they didn’t want to join them, they had 24 hours to leave the island or they would be killed. This is what happens. Central Americans are not just coming [to the U.S.] for a better life, but the conditions in their country are really bad, really horrible, and this happens to a lot of people.

– Kaitlyn Hardy