A Conversation with Jia Zhangke (CAUGHT BY THE TIDES)

Caught by the Tides represents perhaps the most ambitious project in Jia Zhangke’s celebrated filmography. Assembled from footage shot over 23 years, from 2001 to 2023, the film follows the character Qiaoqiao (played by Zhao Tao) as she searches for her lost love Brother Bin across a rapidly transforming China. What began as documentary observations of life in the coal-mining city of Datong evolved into an elliptical portrait of romantic destiny and social change, with Jia weaving together scripted scenes, documentary footage, and even clips from his previous films into a meditation on time, memory, and resilience in the face of relentless modernization.

Jia Zhangke, one of China’s most internationally acclaimed filmmakers, has built his career documenting his country’s breathtaking economic and social transformation since the turn of the millennium. Known for films like Still Life, A Touch of Sin, and Ash is Purest White, Jia has consistently explored how ordinary people navigate extraordinary change, often following characters across decades to capture the subtle ways time reshapes identity and relationships. With Caught by the Tides, which premiered in Competition at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival, he has created perhaps his most personal work, a film that serves simultaneously as a love story, a historical document, and a reflection on his own evolution as an artist over more than two decades of filmmaking.

Hammer to Nail: You’ve assembled footage shot over 23 years for Caught by the Tides. At what point in this process did you realize that these images could form a feature film?

Jia Zhangke: I started filming in 2001, which was the beginning of the new century. At that time, Chinese society was going through a major transformation. Everywhere you went people had lots of energy. They were starting to move toward the new era. You see this idea of transforming not only physically as an individual but also as a city, as a country. That is when I started to make this film and collect footage about what I saw and what drew me to those images, what moved me and what I wanted to capture.

The filming process continued on and off for the past 20-something years. It wasn’t until COVID, during the pandemic, that I had the time to really see this as the moment for me to put everything together into a film. During quarantine, we felt rapid change. Of course, the pandemic is a change itself, but our rapid life suddenly stopped. From the beginning of the century to the pandemic, it made me think back to the vitality of the beginning of the century compared to the reduction of vitality during the pandemic. This made me very emotional. I felt like an era was coming to an end.

Politics were changing, and technology was changing. At that time, I thought the pandemic would be a perfect time to finish this film. It’s such a tremendous change, although by itself, it is a change that we experience when everything stopped. At the same time, there’s such a sharp contrast between the beginning of the turn of the century, that kind of full energy momentum where people are moving around trying to find a better life, to suddenly having this temporary pause where nothing is going on.

I think that’s exactly when I started to realize that this signals a turn, an end of an era. The changes that we saw politically speaking, technologically speaking, within the past 20-something years, somehow this was the perfect juncture for me to put this film together because this is the end of the old era and the dawning of the new era.

HTN: The city of Datong features prominently in the film. What drew you to continually return there over two decades? And how do you feel it represents the economic and social changes in China?

JZ: First of all, Datong is a city in China that is landlocked. This city relied on coal for a long time. But when coal began to decline, the whole city faced a dilemma. It is not as progressive as other Chinese cities. It suffered a lot economically because of the drying out of the coal mines there. It’s not unlike what’s happening in the US around the Rust Belt areas. the similar challenges that are facing communities here in the United States, you can definitely see in China, in the Datong area as well. That is the kind of community and the people that drew me to this particular place and to filming in this location multiple times.

Historically, it is a place where the Han and Mongolian tribes intersect. They are strong and active, like the nomads. A lot of people tend to have this nomadic spirit, this idea of moving around. These are all the special characteristics, historically speaking, that drew me to this particular place.

HTN: The film uses multiple camera formats spanning decades of technological evolution. How do these varying visual textures contribute to the emotional experience you wanted to create? Many filmmakers would avoid mixing digital formats. What artistic possibilities opened up for you by embracing these technological transitions rather than hiding them?

JZ: The original working title of this film was The Man with the Digital Camera. I had just made two movies, Xiao Wu and Platform, and then I started making this film. To a large extent, it was because of technological changes, because of the emergence of digitalization. It made me hope that, because it is very convenient and cheap, and it can be used by a small team, I could make the kind of film I’ve always wanted to do. To bring a camera and actors to capture the direct reaction to life. This is a method I’ve always yearned for.

Many years later, I found that the different textures of different photography equipment define a certain era. When I started this particular project, the digital technology being introduced at the time really drew me to this particular way of making films. It’s very lightweight, it is cheaper. I can just take a very small crew with me and go to the locations and spaces that really attract me and move me. I can have the actors either interact with that particular real space or create some kind of fictional structure or narrative that I want to act out in that particular time and space.

Later on, because production conditions changed and the technology of digital filmmaking evolved and became more mature, I sometimes also used film stock. My production conditions and economic conditions improved.

HTN: At the 28-minute mark, we get one of my favorite sequences. It starts as this animated sequence, and leads into this moment where it’s your friends dancing to some techno music in that small room. Talk about these two sequences, how they came to be, and why they find themselves next to each other in the film.

JZ: First of all, that animation was filmed in 2001. At that time, there was the rise of internet culture. We saw things like internet cafes. Many years later, when I saw this material, I thought that this animation method was very reminiscent of that time. You see commercial brands like McDonalds because they were really popular at the time.

The virtual image of the animation connects with the in-person, real space of a karaoke bar where people listen to music and dance at the same time. That is the juxtaposition and connection of these two scenes. I think it’s a perfect combination to signify that particular age, that particular time and space. The collective memories that we all have of this combination of the virtual world and the brick-and-mortar entertainment we had at the time.

So you have these two dual realities at the same time, the virtual reality from animation that you can’t really connect with in person, but also the real connections that people can form through karaoke bars and singing and dancing together.

HTN: I love this sequence at the 35-minute mark where she keeps standing up and trying to leave the bus and the guy keeps throwing her down. How did this scene come to be?

JZ: This scene has a lot to do with the evolution in my editing process. At first, I was only using the material from the footage I collected for what was going to be Man With a Digital Camera. After editing for a while, I suddenly felt that as a review of my journey of more than 20 years, all the images I shot in these 20 years could be included in this film.

That scene is actually from my 2002 film Unknown Pleasures. Later on, as I was editing all the footage, I was thinking about the fact that I’m looking back on the 20-plus years I’ve been making films, contemplating what I have done in these more than two decades of visual images. Whether the footage was intended for Man With a Digital Camera, or actual footage that I have shot for my films that have been released before, I see all of them as something I should be able to incorporate into this film because they are all part of the visual history and visual images that I have produced as an artist and filmmaker.

I include scenes from my previous films about seven or eight times in Caught by the Tides, repurposing what I had before in my previous films. Through this process, I’m trying to give these shots that already had an identity in my previous films new meanings and new identity in this particular new film. That particular scene perfectly captures the romantic connections, traumas, and challenges between the male and female protagonists. The harms they have done to each other and the trauma they both experience.

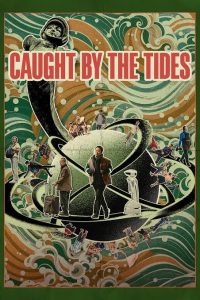

A still from CAUGHT BY THE TIDES

HTN: The character of Qiao Qiao has appeared across several of your films, Unknown Pleasures, Ash Is Purest White, and others. How has your understanding of her evolved through these projects?

JZ: In Unknown Pleasures it is a slice of life about a summer when she’s just in a state of youth. You don’t really know what profession this particular character holds. But when you compare that to Ash Is Purest White, this is a film with such a long time span from the 1990s all the way to the contemporary, and this is a character with a very distinct occupation, someone who is in the underground.

You can see how Qiao Qiao as a character evolved from her youth represented in Unknown Pleasures to someone who has this awakening of their sense of self, the awakening of female consciousness, and independent ability to choose her own feelings. At the end, she becomes very strong. The focus of this narrative is actually to find the changes in her inner world over 20 years of her character.

In Caught by the Tides this particular character goes from being so codependent on her relationship with Brother Bin to evolving into this strong individual with independent thinking and female consciousness, much stronger than she was before. It’s the perfect embodiment of the kind of growth I’m trying to capture through the character of Qiao Qiao and to see the evolution and development of an awakening of self-consciousness and female consciousness.

As an actor, she has been a central figure in my films. She brought very different perspectives and helped us understand change and how people react to changes through her performance in these films. It’s definitely become very complementary to my filmmaking and my perspective, making the films even better as a result of her performance.

HTN: I wish I could talk about this movie all day. I really thought it was so special and it’s definitely going to be one of my favorite movies of the year. It was such an honor to speak with you. I’m a huge fan of your filmography, and I hope to be seated in a theater for whatever you do next.

JZ: Thank you so much.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)