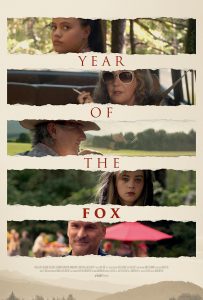

A Conversation with Megan Griffiths & Eliza Flug (YEAR OF THE FOX)

Megan Griffiths’ latest film, Year of the Fox, is a coming-of-age drama that takes place in 1997 Aspen and Seattle. Ivy (Sarah Jeffery) is a young woman on cusp of finishing high school, when she gets a disillusioning peek behind the curtain of her parents’ social circle. There she finds selfishness, deceit, pettiness, judgement, and a ring of untouchable predators. If you are reading this in America in the year 2025, this dynamic may sound achingly familiar. Systematic patriarchal exploitation is as American as apple pie.

As you may have guessed, screenwriter Eliza Flug’s semi-autobiographical tale leans dark. But it’s not a suffocating darkness. As Ivy puts it: “It’s hard to trust the good memories through the bad, but they were just as real”. Griffiths has always been deft at maintaining this verité tonal balance, ever since her quiet stunner, The Off Hours, premiered at Sundance in 2011. Griffiths and Flug are a match made in feminist cinema heaven. Their affinity for a light touch is a breath of fresh air in this perpetual landscape of male-dominated cinema. Sometimes the occasion calls for a Coralie Fargeat protagonist barfing up blood all over the patriarchy, and other times, a cozy, quietly scathing tone poem like Year of the Fox delivers a similar catharsis. Together, this dream team has crafted a formidable film about the ripples created when powerful men use their influence to hurt women – without repercussion – time and time again.

I recently chatted with Megan and Eliza about their journey since the film’s debut at the Seattle International Film Festival, trusting the audience to grasp narrative nuance, the music and films that inspire them, and using art as an act of rebellion.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Hammer to Nail: Thank you for joining me today and for making this incredible film. I felt a personal connection to Year of the Fox because I graduated from high school in 1996 and moved to Seattle for college. The dynamic between Ivy’s parents is very familiar to me. I found myself gasping in recognition, especially when the parents talk to each other because that’s how my parents talked to each other for many years.

Megan Griffiths: Glad it was relatable.

Eliza Flug: Sorry it was relatable.

[Everyone laughs]

HtN: And I also loved that you showed something rarely depicted in movies and TV, which is that an encounter with a predator can be just as traumatizing even if they don’t get what they came for. Just being in proximity to the danger. Seeing that play out on screen was so unusual.

MG: Yes, a near miss can be traumatizing too.

HtN: The film premiered at the Seattle International Film Festival in 2023. What was the journey like from the festival debut to the recent release?

MG: We were working with a distributor and ultimately, they weren’t putting out the film, and so we ended that relationship and worked with our new distributor, Monument Releasing, to get the film [out]. We’ve been waiting anxiously to release the film for this entire period so we’re happy to be getting it out now.

HtN: When did you start production?

MG: We shot it in 2021.

HtN: Wow!

MG: Yeah, it’s been a long journey. It’s not like the COVID era is ancient history but it is weird to think about the fact that we were shooting with a very freshly vaccinated crew with very strong limits on how many people could be in our party scenes and how to get people to be on set together safely. This was all very present in our production.

A still from YEAR OF THE FOX

EF: And on the production side, it was a 15% markup for a COVID nurse to be on set at all times, and on the insurance cost. On my end, it was interesting to see that happen. There had been shutdowns in L.A. In the month while we were filming in Colorado and Washington state, we’d had one within less than two months. So, getting together as a community was special. It was actually really nice to see humans and be together. It was a really special time, for sure.

MG: Yeah, and it was a story we were both really ready and excited to share, and it’s just been a challenge. I mean, the entire film landscape is a challenge right now, so we’ve just been part of that – the issues that are affecting every filmmaker these days.

HtN: Yeah. And issues that are affecting every woman. I mean, you shot this so long ago and it was as true in 1997 as it is today in 2025. So many truths in this movie.

You both complimented each other creatively on this film. Eliza, in your writer’s statement for the film you talked about how power is always better when it is shared. [Author’s note: The full quote is, “It was freeing to write this reflection and to see Megan Griffiths, a filmmaker I respect, take what she read and create this translation, to work with her and to learn about power, and how it is better when it is shared. Always.”]

How did you share the power when you were collaborating on this film?

EF: I think that you choose it, and you’re very selective on how you do something, especially if you want it to be relatable to other people. You have to be true, and you hope for that truth and integrity in the relationship. It’s not something you can force. And it’s something you come by honestly every day. And so, Megan led the charge on that with production and with her community – our shared community of women working together, wanting to create something that would speak to our children. It was more about, “what do they think of this and what will they see?” Making film can be very selfish and making art is very self-involved, but it was an act of trying to create something for other people as opposed to just being about the past or the self. I think we both came from that perspective, which made it easy to work together.

MG: I think we had a shared desire to have this conversation be – not just something that was happening between the two of us over coffee – but having with an audience. Within our culture the conversation’s gotten a lot louder recently because of what’s leading the headlines these days, but it’s not new. The idea of talking about sexual politics, talking about predation, both sides of the coin – the people who are predators and the people who are interreacting with them and having their lives impacted by them – these are all conversations that have been going on since way before this movie, since way before Jeffrey Epstein, but they’re coming to a head culturally right now and I’m glad we’re able to contribute our little piece of the puzzle.

HtN: So, I have a Twin Peaks podcast and I’m a bit of a David Lynch scholar, so I’m trained to notice Twin Peaks connections everywhere I look, and I saw an awful lot in your film. And I was wondering if it was more than coincidental.

EF: It was intentional, for sure. It was really cool. Did you know our production design team did Twin Peaks? A woman named Lauren Fitzsimmons – so there’s a Jell-O mold in the kitchen at the end of the film that was one of the pieces that they did.

HtN; That’s amazing, I didn’t even notice that one. I know you also shared a location manager with The Return [Dave Drummond].

MG: Yeah. He has fun stories of being in a scouting van with David Lynch.

HtN: Oh man, I bet! And then of course Jane Adams and Balthazar Getty [were also in Twin Peaks: The Return]. And then Layla even looks a bit like Laura Palmer in a few scenes. Was that intentional?

MG: Not intentional, but I love that. That’s great.

MG: Not intentional, but I love that. That’s great.

EF: She was cast because she looked like the friend that inspired the writing. And because she had the best audition for that character. Period.

HtN: Both the leads [Sarah Jeffery and Lexi Simonsen] were absolutely phenomenal. How did you go about casting and finding those two?

MG: We worked with a casting director named Amey René. I’ve worked with her several times [Sadie, The Night Stalker]. She’s very good at finding up-and-coming, amazing talent; and in this case that was really useful to us. [laughs] And having great ideas for established actors for the adults. She came to us with the Balthazar Getty idea, which I thought was a really good one. He came in and really delivered on what we were going for there. But Sarah Jeffery and Lexi Simonsen – who play the two young leads – they both came in via Zoom auditions. They did a recorded audition that we reviewed alongside a lot of other ones. We were both were kind of narrowing the field as we watched and comparing notes and then we called them back for a second audition over Zoom… everything was over Zoom, since it was 2021. And really one of the things that was useful… I’ve done this before; I don’t know how common it is, we cut together their auditions so we could kind of feel how they would work in a scene together, and what their chemistry might feel like. And even though they weren’t actually in the same room, it does give you a sense of things. It just felt like they would be friends. And then they came and met each other on this movie and have been very, very good friends ever since. So, I guess we called that one. [laughs]

HtN: It really comes through. They really seem like they’ve known each other since childhood. It’s amazing.

MG: And Jake and Jane have known each other since the 90s as well. They went to Julliard together back then.

HtN: Oh wow! Obviously, their relationship was a bit more combative, but their dynamic was solid. The performances were just fantastic across the board.

MG: Thank you.

HtN: For Eliza, there are a lot of recognizable moments in this film that I can’t recall seeing depicted before, [such as] the complex dynamics between girls when they’re in a situation with predators. Layla was a little jealous of one of the other girls who seemed like she could hold her own, but really, they’re all being equally victimized. And at the same time, you were telling your own story. How do you balance all of these complex themes while keeping the story personal?

EF: As you might know and as all women know, there are so many of those themes happening every day when [we’re] just walking through our lives. And so, it makes it pretty easy to pick and choose the moments that layer together to create the context of who you are and how you act in those situations. In your teenage years, that’s when you start to look at your role models and question their integrity. So, I was trying to go back in time and write about that perspective, that I recalled, of my parents and of the community that I was living in, which was an amazing community of brilliant people. Highly successful, highly educated. I couldn’t have been luckier to be in that community. And yet, to see that they were just as capable of being horrifically, morally corrupt. You know, 99% [of them] weren’t, but the specific people with the most power and the most say [were].

I used Jenny Holzer in the screenplay because she’s one of my favorite artists – period – from the 80s and 90s and she’s still relevant now. [Her work was inspired by the Lord Acton quote] “absolute power corrupts absolutely”. It’s something that stuck with me after going to the Whitney biennial in my teens and being like, “she’s so right.” Looking through the lens of that statement: These are the people that are designing CERN. These are the people that are shaping our defense systems. These are the people who are deciding who is going to live or die in Uganda or Rwanda or Gaza. These are the people that are affecting our world climate. So, they’re having all this say but they’re doing this shit on the side. How is this good for our country? How are we wondering why Donald Trump is president? It’s like, look at our choices. Look at what we chose. Look how we treat each other. Where does this come from? So, as a teen, it was setting me off then. And I think a lot of young people now, who are really engaged and active in their own voice, would [agree]. I don’t remember in the 90s, [having] a lot of avenues for young people to voice their discontent, except for in their journals. We didn’t have social media and all that stuff…

MG: Yeah! Your Tik Tok would have been off the chain, Eliza.

[both laugh]

EG: I would have been KICKED OFF!

HtN: I’m so glad that you mentioned journals because in screenwriting, a voiceover can be sort of a dicey prospect. But I thought here, it was deployed perfectly, and it really did remind of a journal, like Veronica Sawyer narrating Heathers or Laura Palmer’s diary. I was just blown away by how well that choice worked.

EF: I’m glad it did because it was one of those things where you go back, and you look at the stuff you wrote as a kid. [Everyone laughs] In filming, we didn’t have voiceover right away. It was one of those things like, do we keep it, do we not? Do we use it? And that was a director choice. Megan was wanting to be inclusive of anything I wanted to express, because she’s one of those people that’s looking to [always] hear everyone’s voice. And then picking and choosing [what works]. It’s really an extraordinary skill that she has. The voiceover was a risk. But I’m hoping it [invokes] that inner voice that you have when you’re young that maybe your adults aren’t hearing. That was the point of it.

A still from YEAR OF THE FOX

MG: And Ivy is such an observer, like Eliza was saying she is. That’s something that’s part of the character. She’s often just in a room watching everybody else and how they’re interacting and trying to absorb and figure out which of their behaviors to emulate and which to run screaming from. A lot of that stuff is playing out on Sarah Jeffery’s face. It’s there in the performance But I think it gives it a little more universality to allow all the audience members to get some of these nuggets of what’s going on here. If you’re not a teenage girl or have never been one, you can still have access to this inner world.

HtN: Absolutely. There was so much that these characters weren’t saying to each other. It really worked very well.

Megan, you’ve always been a master of telling difficult stories about women without making the viewer feel victimized or like we’re drowning in the misogyny. There is a lot of visual and narrative shorthand you use to refer to the exploitation, that made it very clear what was happening without actually showing it. Do you have conscious techniques you employ or was it a more intuitive process?

MG: There’s definitely a thought process there, especially with a film that has this kind of subject matter. I want it to be available to as many people as possible. I don’t want to cut off the audience that is allowed to watch it. I also have a strong faith in the audience and their imaginations and how they can fill in the gaps for things. I think the implied thing can almost be worse sometimes. That was something that I was definitely playing with a lot on my film, Eden [about sex trafficking], that I made many, many years ago. Playing with it in that film has rippled out across my career. Reading the response to that movie – all the things I was hoping people would get, they got – plus more – by me not showing it explicitly. I feel like that’s always a useful choice.

HtN: Yeah, the Jaws effect! I loved Eden too. That was an amazing movie.

MG: Thank you.

EF: It was the first movie I’d seen of Megan’s, and then I went back and watched The Off Hours.

HtN: The Off Hours is my personal favorite. It’s so quietly beautiful.

MG: Thank you. It’s my first born. I made a film before that, but The Off Hours took so long to make and get it out into the world, and it was such a challenging movie to get made. But then [it] had such a life to it. It occupies a special place in my heart.

HtN: The film references Ingrid Bergman, specifically her film, Indiscreet, which is about infidelity (a theme in Year of the Fox), but she also famously starred in Gaslight, which is also going on quite a bit in [the narrative]. Are there any other classic films that you had in mind during production?

EF: Yeah, National Velvet was one of them. I’m a film dork. That’s my thing. People called me “Blockbuster” in college because they’d come borrow movies from me. And National Velvet was always on rotation. “So, Mickey Rooney’s how old? [24] And Liz Taylor is how old? [12]” And then they remake it [International Velvet (1978)]. I saw it in the theater in 1981 when it was Tatum O’Neil [age 14 – opposite 24-year-old Jeffrey Byron]. I was like, “OK. What is the deal here? Why is this hot? This is creeping me out”. So, looking at the context and through the lens of these films where women are being chased or sexualized or objectified, it was like what is that teaching? How to relate to each other or how to be personable? So National Velvet was up there. Ingrid Bergman’s one of my all-time favorite actresses, so she had to be in there.

MG: I didn’t know that, and I haven’t seen Gaslight yet. I was just talking about that with my husband yesterday. It’s a good time to watch it, probably. [laughs]

HtN: It definitely is. You probably know everything in it already because it’s just inherent if you walk through life as a woman.

Balthazar Getty’s character, who’s just called “The Fox”, essentially weaponizes Ivy’s love of Ingrid Bergman. Do you have any real-life examples of beloved media that was ruined for you by predatory men?

MG: The Cosby Show.

HtN: Oh yeah! That’s a great answer.

MG: I really loved that show. Malcom Jamal Warner just died recently so it’s fresh in my mind. It was a big show for me growing up so to have it tarnished by learning what we’ve learned about Bill Cosby is really a drag. And, like, all of Woody Allen’s work. And Polanski. There’s a lot. Where do we stop?

[Everyone laughs]

EF: The transference between my dad and an older man that I wrote about. Some of my male relationships growing up, while the men were very successful and seen as very moral in the community, doing great things for others, they had side gigs going on that were just nefarious. It was looking at the people that I was supposed to have great respect for and realizing that they weren’t as wonderful as they wanted everyone to [think]. That was very hard for me. I had a really hard fall, and I don’t talk to some of my family anymore because of it.

HtN: Thank you for that answer.

I wanted to ask about the music for the movie, because I noticed some 90s songs that the girls would have been listening to but there’s also some Dad Rock present, like Don Henley. Can you talk about the process for choosing the music?

A still from YEAR OF THE FOX

EF: Well, Don was one of the people that I knew growing up in Aspen… He’s someone that people really love in town. And I love the Eagles. And I listened to a lot of the Eagles while I was writing to get my brain back into the 80s and 90s, when I was growing up in Aspen. So, the soundtrack was my brain writing the screenplay and adding in the music [from] that part of my life. Like Porno for Pyros. I had a lot of Jane’s Addiction [albums] growing up. It was a big part of my daily soundtrack as a teen.

MG: There [are] different categories of music on the soundtrack. One is, as you mentioned, Dad Rock. There’s a lot of stuff that’s more 70s – that is what her dad is listening to or what is playing in scenes with her dad. And then there’s 90s music that is playing in all the scenes [where] the teen culture is being depicted. And then there’s 80s music because…

EF: Ice rink!

MG: …Nothing current is usually playing in ice rinks. There’s always 10-years-ago music playing. So, at that point, that would have been the 80s. We were trying to be conscious of what you would have heard in these environments in [1997].

HtN: And what about the score by St. Kilda. What were you looking for in terms of the score?

MG: I’ve worked with them a lot. They’re really good at translating emotion into music and to be this relatively unobtrusive lift to all of the emotions that are happening in a scene. I’m kind of sensitive to a score [that] is overplaying things. I really value subtlety. It’s a whole different language, you know? Speaking in music. I can say to them, “this is the emotional beat. What do you think that translates to?” They come back with something that just lays right underneath it and gives it some dimension and draws the audience in more. At least, it does that for me.

HtN: Yeah. I think that really comes across.

I know you shot in North Bend, WA and Aspen, CO. But for the scenes in Seattle, I was curious what neighborhood you had in mind for where Ivy and Paulene live.

EF: It was supposed to be Madison Park. And it was filmed nearby.

HtN: I just love that scene where Ivy and Paulene are meeting their neighbors. It’s so Seattle. The [passive aggressive] way that they relate to each other and the way that the neighbor’s daughter is shooting death glares at her mom. As a Seattle resident it really… uh… resonated. [laughs]

MG: Excellent. That’s great to hear. I love that scene, too. Jane cracks me up in that in that scene.

HtN: She’s fantastic.

One more question for both of you: How difficult is it now to make independent films about women? What are the roadblocks that you’ve experienced? What avenues have been successful?

MG: It’s funny, I’ve rarely made independent films about anyone who isn’t a woman.

[Everyone laughs]

MG: But I do think films that center women’s perspectives and stories are the ones that you see less of in the larger studio world conversations and every film [needs] support to get it made, [no matter the] sector or level. It’s just being able to find people who want those stories told. And I think it’s hard at every level, but in the independent film world, at least, you can find people who value that. Eliza and I worked together on my film, Sadie. Eliza really values getting under-told stories out into the world, so in this case that made it a lot easier.

EF: I do value finding unique voices and talent that have a quirk or something that makes my weird little brain go “ooh I want to see that happen. I want to work with this. I want to be a part of this.” That’s one of the cool things about working with an art community like [the one in Seattle]. People are really intentional. They’re making art. It’s something that they’re really into. There [are] a few different people that come to mind right now that are making beautiful art. Some of it’s in big festivals this year. And I’m really excited for them. Being part of their work makes me more inspired to do my own and have my own voice, but at the same time to be part of theirs. To see their work through, it just makes me so happy.

MG: Working in the independent film ecosystem [can be] challenging on so many levels. But it’s also really nice to be part of a system that… you watch organizations like Paramount, bowing down to larger political influence. There [are] stories out there that are just not being told or are being silenced because of these major power structures. To be working outside of that is kind of nice and I’m grateful to be able to put this [film] out in this climate.

EF: What makes you independent is your resilience, right? What makes you have a voice is the thing that people can’t take away from you. And everyone’s trying to [do just that], especially this past year. I hate to go that way… because I don’t like to be part of a big collective noise. But I think it’s really true. And independent film is the last bastion of trueness. I don’t want to be part of the Big Wheel. Unique stories come from people who have to tell it no matter what. And that is something that AI can’t generate. Thank God.

MG: Hear, hear!

HtN: Those are beautiful answers. I really appreciate it. And I do think this type of art is an act of rebellion and it’s a very important one. Thank you both for making this movie. I loved it so much.

MG: Thank you so much. I’m really happy to hear it resonated.

Year of the Fox is playing in select theaters in Seattle, WA and Portland, OR from July 18th, 2025, and in Los Angeles, CA from August 1st. It will be available nationally on digital platforms from August 19th, 2025.

– Jessica Baxter (@TheBaxter)