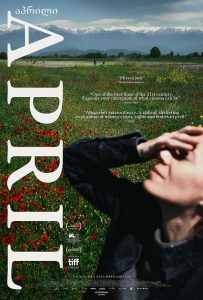

A Conversation with Dea Kulumbegashvili (APRIL)

Georgian filmmaker Dea Kulumbegashvili has emerged as one of world cinema’s most uncompromising voices. Her debut feature Beginning (2020), which won four major awards at the San Sebastián Film Festival, established her as a director capable of creating profound tension through patient observation and formal rigor. With her sophomore feature April, which won the Special Jury Prize at the 2024 Venice Film Festival, Kulumbegashvili continues her exploration of women navigating patriarchal systems, this time through the story of Nina, an obstetrician who risks her career and freedom by providing illegal abortions to women in conservative rural communities. April represents a significant evolution in Kulumbegashvili’s filmmaking, blending stark realism with moments of surreal transformation to create one of the most visceral films of the decade. Produced by Luca Guadagnino and featuring lead actress Ia Sukhitashvili in another collaboration with the director. Through her distinctive visual language, characterized by long, unbroken takes, and a tactile attention to bodily experience, Kulumbegashvili crafts a work that is simultaneously intimate and epic. See this movie in a theater if you can. The following conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Hammer To Nail: You’ve worked with Ia Sukhitashvili on both Beginning and now April. How has your collaborative relationship evolved, and what specific qualities does she bring to the character of Nina that made her essential for this role?

Dea Kulumbegashvili: Ia is a perfect actress. She is my friend and I communicate with her often. But then, still, from one film to another, it feels like you don’t know her at all. When you start to prepare for the film she comes in as a very different person. It’s her intuitive response to the material. When we made Beginning, Ia, not much earlier, had given birth to her second child. She was in a very different emotional condition. She has a lot of postpartum that you can feel in that film, however, for April she was a totally new person. She had a lot of anger and rage because of certain things that were happening in her life. All the great actors are not easy actors. It’s always a challenge as a director to leap out to whatever they give you. Ia is incredibly challenging in that way and I am so grateful for that. She forces me to do my absolute best. When we talk about character, she starts to give so many different interpretations, and all of them are so interesting and good. You start to question yourself as a director. You think, “is this what I am looking for?” It’s so great to start from zero and build the character together. She is so open and willing.

HTN: Your filmmaking often involves non-professional actors from the local communities where you shoot. How does this approach enhance the authenticity of your storytelling, and what challenges does it present?

DK: It’s not necessarily about authenticity, it’s really about these people bringing something to the film that I could not have thought of. It is a challenge because when you put them in a scene with a professional it can become easy to see the flaws in their performance. It is also challenging for the actors! We had so many conversations about it. We rehearsed a lot for this film with the non professional actors. Through these rehearsals we start to feel what the other person is doing so everyone can get on the same page. I am a firm believer in work shopping the scene because it helps me rewrite according to the people who are going to be acting in the scene. It’s not something theoretical that I write and people come and do it, we make it all together

HTN: The tone is so specific and everything is so intricately designed that it is not surprising to hear. You mention creating a specific atmosphere on set, keeping things calm, avoiding shouting “Action,” positioning yourself near the camera to communicate directly with actors. How do these production choices affect the performances you’re able to capture, particularly in emotionally demanding scenes?

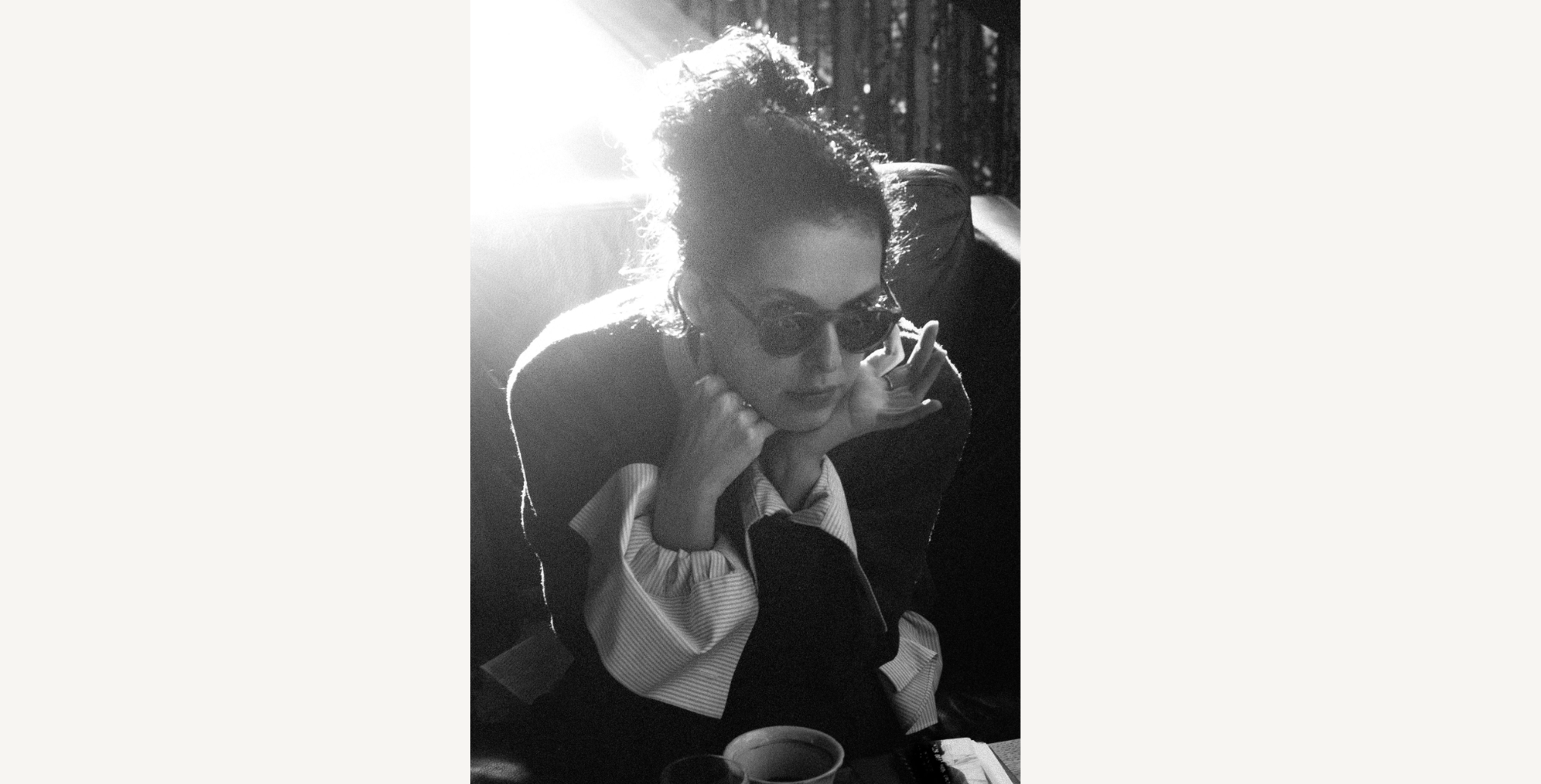

Ia Sukhitashvil in APRIL

DK: I trust the actors and I trust the camera. I want to create circumstances for something to happen which was not written. I am always going for something more than what’s on the page. Something beyond what I originally envisioned. It’s very important for me to be next to the camera because I need to feel everything going on in front of it. When I am far away with a monitor, I start to lose my sense of connection with the camera and what is in front of it.

On the other hand I like to be next to the camera because I love talking with the actors, even as we are filming. They are very much aware that even if I am talking to them they need to keep acting. Sometimes it does not pan out and someones gotta interrupt me because I am ruining the shot, however, other times it can be very interesting what happens. We will rehearse a scene one way, and then I will surprise them and tell them to do something else. For example I whispered to Ia “Do not stand up” right at a moment she had rehearsed standing up for so long. That brief moment of adjustment, of uncomfortability, the camera grasps it. At the end of the day, what is authenticity? I do not know in this case because this is also authentic because she really feels uncomfortable. It becomes acting and not acting at the same time. Especially with someone like Ia, who is technically perfect, sometimes you need to bring her out of her comfort zone of this technical perfection.

HTN: I love the design and use of this creature. Every time it comes on the screen it is such a shock to the system. Can you discuss what was important to you in the design of this creature as well as these initial introductory moments?

DK: We had to shoot the creature twice. It was a very interesting learning experience for me. We made a technical mistake, our first time around. You cannot pretend that something that does not look very alive on set is going to be in post production. It was something I could not fully accept. I needed it to look real, particularly the skin and flesh of it. The movement was also very important. It is shot on stage. It feels like there is water but there is none. This is where the magic of cinema starts to happen. You start to think in terms of sound and what it could do to this image. I wanted the audience to feel the water in the opening shot even though it was not actually there. Her getting into the void of the water itself. I wanted that to feel experiential without much specificity or narrative structure because it creates these glitches in their reality. I hope it makes the reality even more real.

HTN: I love the sequence around the 30 minute mark where David confronts Nina. At first it seemingly looks like a POV angle before Nina hops into the frame and David and her hug. At one point Nina says to David that the woman was so peaceful and tranquil after the baby passed. David responds, “don’t say that nonsense to anyone.” Talk about what was important to you at this moment.

DK: I shot this scene twice as well! Very rarely do I shoot things twice. The first time we did it, it was a perfect moment between two actors. But nothing really accumulated. It was what it was. You could not feel that magic of cinema that I needed. The accumulation of tension and emotion. Something that goes beyond good acting. The problem was the positioning of the camera. We changed it and this embrace of them touching each other, I wanted to emphasize how important it was for both of them. The dialogue here really questions the stigma around what childbirth really is and how much happiness it needs to represent for a woman. Is it always happiness? Maybe it is not. If it is not, is a woman allowed to express that? If she does then what happens?

HTN: After the abortion sequence at around the hour and a half minute mark, the camera dangles around this landscape as a heavy storm brews. This leads to the camera catching Nina’s car getting stuck in the mud. The visuals in this moment have not left my mind since I saw it in theaters. What was your thinking here?

DK: This was a beautiful storm. We knew it would happen. We had passed by this field so many times in preparing for the film. For over 3 years the cinematographer and I were in this place. We were so overwhelmed by some of the things we encountered in speaking with the village members and visiting these homes. On our way back to the hotel, driving through these fields, we would not talk to each other. It was really difficult on some days to handle the reality. Sometimes we would see a beautiful storm or rainbow over these fields. We would stop the car, get out, and walk around. It was important for me to grasp this feeling that despite everything, this spectacular and beautiful nature is still there. Everybody can bring their own meaning towards it. For me it’s important for the viewer to see that these flowers are just flowers and feel warm. The world we live in is everything at the same time. It is not just a miserable experience or just seeing the beauty of nature, It’s everything at once. Just like a storm itself! Maybe the flowers are ruined after the storm. You see the vulnerability of nature as well.

HTN: The film includes scenes of real childbirth and medical procedures. Could you discuss the ethical considerations and practical challenges of incorporating these moments while maintaining your artistic vision?

DK: It was very important that we spent a year in this clinic. I have seen many other women giving birth. I really understood where I could put the camera. It was really clear to me that I also needed to be out of their way. It needed to be in a place where it would cause no distraction for them and they can completely focus on the actual medical procedure, obviously. No one from the crew was inside that room. We were all separated by a wall. On the other hand, in terms of ethics, it was not even a question for me. Once I was in this clinic, with these women every day, following their pregnancies and they were so open about them, I started to see the importance it represented for them as well. I wanted the birth to be an actual birth, not just an extra social commentary. I wanted the audience to grasp this moment for what it is, which again is everything at the same time. Misery and beauty. It was also so humbling. As a director you think you create everything and it’s your own vision, but here you just need to get out of the way and step back. This kind of generosity is what makes cinema possible. I am not just appreciative of it, I am extremely lucky. This film, much more than my first feature, is very much a collective effort. Not only because of the birth scenes, but all the women who made this film possible through their stories, bringing me to their houses, walking me through their very personal and painful experiences and, of course, all the doctors.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)