A Conversation with Joanna Natasegara, Abigail Anketell-Jones, Chloe Lambourne & Cyrus Bozorgmehr (THE DISCIPLE)

The Disciple is a documentary about the creation of Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, the Wu-Tang Clan album famously pressed as a single copy and sold at auction for $2 million in 2015—the most expensive piece of recorded music in the world. The film follows Dutch-Moroccan rapper and producer Tarik Azzougarh, known as Cilvaringz, an obsessive Wu-Tang fan who through relentless determination earned a place in the group’s inner circle and became the driving creative force behind the controversial album. Conceived as a statement about music devaluation in the streaming age, the album was encased in a handcrafted silver box and sold as fine art—only for the buyer to be revealed as Martin Shkreli, the pharmaceutical executive who became “America’s most hated man” after raising the price of a life-saving drug by 5,000 percent.

Director Joanna Natasegara is an Academy Award-winning filmmaker whose credits include the Oscar-winning short The White Helmets (2016), the Oscar-nominated Virunga (2014), and the Oscar-nominated The Edge of Democracy (2019); The Disciple marks her feature directorial debut. Producer Abigail Anketell-Jones has worked across Violet Films’ socially-conscious slate. Editor Chloe Lambourne shares credit with Oscar winner Chris Dickens And Cyrus Bozorgmehr, who served as senior adviser on the Shaolin project and authored the 2017 book Once Upon a Time in Shaolin (named one of Rolling Stone‘s Top Ten Best Music Books of the year), appears in the film as a key participant. The documentary premiered at the 2026 Sundance Film Festival. These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

JOANNA NATASEGARA (Director)

Hammer to Nail: The film was adapted from two books—Cilvaringz’s memoir Fanboy and Cyrus’s Once Upon a Time in Shaolin. Can you talk about interacting with those texts?

Joanna Natasegara: As you see in the film, there is an element of Tarik telling his own story. There are parts of that autobiography that he chooses to forefront, and then you get into the clan story and the genesis of the album. It was really important to me to honor that, because as you see in the film, I interact with him and ask him why he does that. It creates a kind of self-reflection that I think is really interesting, and a narration—a storyline of this album he made.. Cyrus’s book is a rendering of the album creation and the sale, which is of course the other end of the story. It is just a really good read.

HTN: This is your feature directorial debut. What made this particular story the one you wanted to step behind the camera for? And how did your producing instincts shape your approach as a director?

JN: The access part is quite similar. In terms of building trust with contributors, from Virunga to White Helmets, I have always had that relationship with community contributors—explaining why we make the story and how they can really work with us. Having that chat with them is really similar to what we did here. But for me, lots of Tarik’s story resonated with my own experiences growing up in a migrant family in Europe, not having much representation and actually being attracted to the Clan and other artists in the US. That was really resonant for me. We are about the same age.

HTN: Once Upon a Time in Shaolin was an album conceived as a statement about music devaluation in the streaming age and an argument that music deserves the same reverence as fine art. As someone who has produced Oscar-winning work about undervalued subjects like Syrian rescue workers, do you see parallels between Cilvaringz’s mission and the stories you have told before?

JN: There are a lot of similarities in the characters that we tell stories about. Whether it is the rangers of Virunga, the White Helmets, or Tarik—there is a lot of resilience. These are people that have big ideas and dream big and then they carry it through. That is the kind of through line I think about in my work.

Joanna Natasegara:

HTN: Why did you feel that the story at the beginning of the film, where Cilvaringz and his sister were involved in that violent attack when he was very young—which is repeated again later in the film—was essential to understanding not only his story but also the story of why this album was sold in the way that it was?

JN: He is the emotional heart of the film. The building blocks of what makes someone. Those are his earliest memories. All of our earliest memories influence us and they create character. He has had so many horrible things happen to him and yet he continues with determination and gives such a message of hope—to kind of go for it anyway. Do not let these things get you down. You have got to keep moving.

ABIGAIL ANKETELL-JONES (Producer)

Hammer to Nail: You have produced across all of Violet Films slate—Virunga, The White Helmets, The Edge of Democracy, The Heart of Invictus. Those films tackle armed conflicts, humanitarian crises, and political corruption. So how does the story about hip-hop mythology and a pharmaceutical villain fit into that portfolio?

Abigail Anketell-Jones: Its a story about the ethics of music but its got some complications. Its about a young immigrant man who loved music but felt like an outsider. He was the ultimate fan and he achieved his dreams. It is about that—about fulfilling your dreams and working hard to do that.

HTN: You have been producing partners with Joanna for years, but this is her directorial debut. How did your working relationship evolve when she stepped behind the camera?

AAJ: Producing for one of the best producers out there was daunting. But it has been amazing adapting into this relationship and seeing her flourish as a director, seeing her creative vision—which came so strong at the start—coming through to fruition. It has been really beautiful, and our partnership has just grown really fast. It has been wonderful.

HTN: The film draws on Cilvaringz’s personal archive and the archives of figures like Shabazz the Disciple and DJ Suicide. What was the process of sourcing and verifying decades of footage from a pre-smartphone era?

AAJ: The archive was beautiful and golden. Cilvaringz had such an incredible archive. That is what makes up most of the film. All of this footage from when he was very young. From back when it was him with his own group all the way to now he had such a rich collection of film.

CHLOE LAMBOURNE (Editor)

HTN: You share editing credit with Chris Dickens, Oscar winner for Slumdog Millionaire. How did you guys divide the workload, and what did you learn from collaborating with somebody like that?

Chloe Lambourne: He is a legend and it was amazing working with him. We kind of worked on the entire film together. We swapped bits around, just trying to make something cohesive. There was so much footage. This is a 30-year story with 30 years’ worth of archive, and all the fan archives as well. There was a lot to get through. But I think we understood what we were going for. It was a shared vision, so it was a beautiful collaboration, actually.

HTN: Documentary editing involves discovering the story in the cutting room rather than following a script. What narrative threads evolved in the cutting room that you did not anticipate from the start:

CL: Most documentaries you are working on finding this narrative and really dragging it out. With this, the problem was that there was too much story. This is an epic story of this album, a fan boy rising to join his heroes, his idols and I think what we were trying to do the whole time was cut out bits of story. What could we lose to make it more cohesive?

HTN: Martin Shkreli is essential to understanding the album’s notoriety, but he risks overwhelming any story he appears in. How did you calibrate his presence—enough context without letting him hijack the documentary?

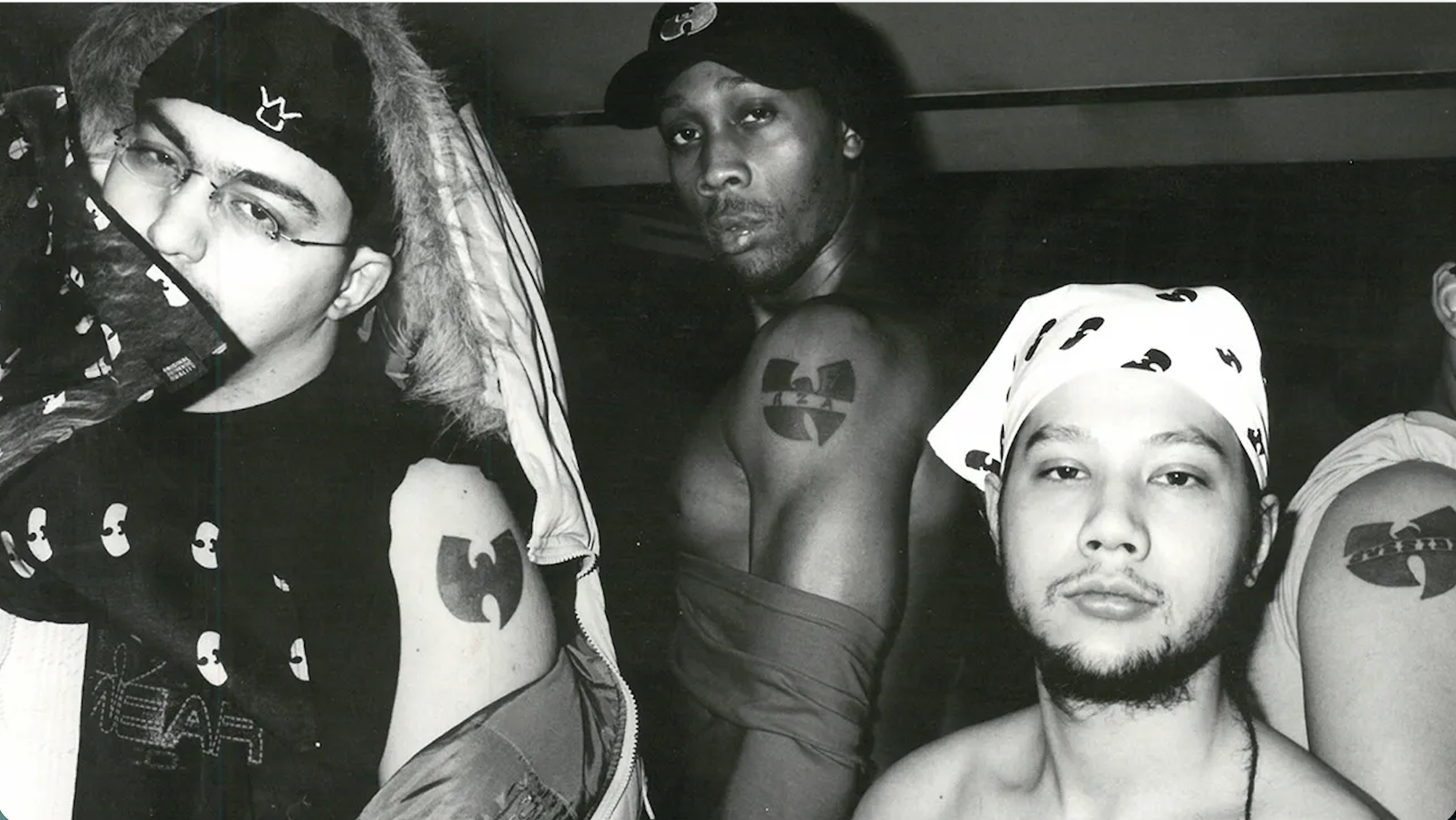

A still from THE DISCIPLE

CL: It was something that we talked about a lot. Striking that balance. This story was about more than Martin Shkreli. He is a huge character in it. But really, it is Tarik’s story. I think we followed that thread, and the thread of the Disciple, and him and RZA. Everyone else is kind of a supporting character, and how that central storyline was affected by the other people as well.

CYRUS BOZORGMEHR (Film Participant / Author)

Hammer to Nail: You were so incredible in the film. Have you considered a career in acting? You were electric on the screen. Anyway, you came into the story as an outsider—a British creative consultant, not a hip-hop head—brought in by an anonymous investor. How did you end up advising on one of the most audacious projects in music history? And what was your initial reaction when Cilvaringz explained the concept?

Cyrus Bozorgmehr: The funny thing was, I had met Cilvaringz before at a party, about three years before I even came on. When he first pitched me the idea, I was horrified. I was like, this is an elitist horror show. What do you mean, private album? But from that time to three or four years later when an investor picks up the phone and says, “I have got this crazy-ass project that you would be right for”—by that point, the industry had changed to the point where I felt that making a really extreme statement made sense. This was not about giving albums to rich people. It really was not. The community that democratically supported music had stopped. If people are not going to pay their five bucks or ten bucks, something has to give. Sometimes an artistic statement has to be so extreme that it is a wake-up call, and you meet somewhere in the middle in the end.

I went in eyebrows deep at that point. I really, really believed in it, and I went way beyond my remit. Instead of general consulting, it became part of my identity. We all became really good friends. It became a real journey because so few people were involved in it. Me and Cilvaringz, we did the lawyering—neither of us are lawyers—just because we did not really trust anyone. That intense bubble of doing something you believe in while always being questioned and abused it was a really interesting process. I am really proud of it, and I am so pleased that the human story behind it is now being told. People are expecting a Wu story or a crazy album story or something about pharmaceutical executives. It is about none of the above. It is about a kid with a dream, and the human element of what relentless determination and insane self-belief will get you.

HTN: Speaking of that human element, your book reads like a thriller, not a music industry memoir. How did you approach telling a story that has Wu-Tang philosophy, art world pretension, federal law enforcement, and the biggest beta villain of our time all competing for attention?

CB: I wrote the whole thing in a month. I did not want to write it. I was like, no, it is weird, I should not—I was involved. Let us get a journalist, let us get an external eye. Then I did my leg in at the Shaolin Temple in New York, and I was on crazy amounts of morphine for the next month. I was like, I cannot walk, I cannot do anything—let me maybe take a crack at it. I did not overthink it. I did not plan it. I was close enough at the time, and I literally approached it like it was a three-bottle-of-wine story in a bar. If we sat down and we were friends, that is how I tell the story. By not overthinking it, I think it just flowed. There were no notes, there was no structure. It just happened.

HTN: That book came out in 2017, before Shkreli’s conviction, before the government seized the album, before PleasrDAO bought it. How does it feel to have the story continue to evolve beyond what you documented, and does this documentary give you a chance to tell another chapter?

CB: What the documentary does is tell the human story, because my book read more like a thriller. This is much more of an intimate portrait. We are delving into childhood. It is a much more intimate portrait. In terms of the album, it is kind of the gift that just keeps giving. Early on, even around the Shkreli reveal, when the horror set in—it was this guy, the guy we had been talking to, oh my God—at that point we realized the genie was out of the bottle. Control was out the window. It had a life of its own. Conceptually, you really want to reach that, but you need to let go. Now it has got new owners. I am trying to step further back. I am trying to kind of de-passionize, but I am really pleased that it has got an independent life, and long may it continue.

HTN: You live in Marrakech and describe yourself as someone who gets embroiled in bizarre adventures. How has your involvement in Once Upon a Time in Shaolin shaped your subsequent work as a creative consultant? And what is the weirdest project you have been pitched since?

CB: What really happened is that I got approached by about nine million startups, all trying to save the music industry, all kind of crypto-adjacent in some way—there was always some sort of crypto token angle. To the point where I was like, no more of this. So I have kind of moved away. I still select artistically crazy projects. I will only do stuff that really speaks to me, that I believe in. That was the thing with Shaolin—I would never have done it the first time I met Cilvaringz because I did not believe in it. I only did it in the end because I did.

The craziest project actually—I am still working on a project to make giant mechanical dragonflies out of former military helicopters for 50,000 people at festivals, with Aboriginal elders singing in it about their own story about a dragonfly that dates back 5,000 years. It is that kind of crazy shit. It is all about repurposing the machinery of war into unifying spaces. There is always an artistic end, there is always something.

HTN: You wrote that the project raised questions about our relationship with art, music, technology, and ultimately ourselves. Ten years on, with streaming more dominant than ever and NFTs collapsing after a brief hype cycle, what is your verdict? Was Once Upon a Time in Shaolin ahead of its time, or was it a timeless statement?

CB: I think it was a timeless statement. I think Spotify has won that battle in many ways. But the arena is changing. In the last 10, 15 years, things have moved from product to experience generally. Live music and live events have become way more powerful and special. People are directing their energies and passions into shared experience in a different way. The resurgence of vinyl has been really interesting. There is still space for people who are really into music to connect with it. They stream on their headphones all the time, but there is something missing. There is some ritual element, some physical element missing.

I think we are going to see that kind of thing with AI as well. At some point, purely human creations are going to have a rarefied premium in the same way as vinyl does. So I think in some ways, it is a precursor for what is going to happen in the film industry. In that sense, it is a timeless statement. It was not the answer to the music industry, but I think it is a question for all of us.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)