A Coversation with Laura Poitras & Mark Obenhaus (COVER UP)

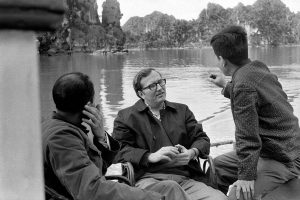

Seymour Hersh has spent six decades doing what few journalists dare: telling the American public what its government desperately wants to keep hidden. From his Pulitzer Prize-winning exposé of the Mỹ Lai Massacre in 1969 to his groundbreaking reporting on CIA domestic spying, Watergate, and the Abu Ghraib torture scandal, Hersh has consistently delivered counter-narratives to official state accounts, often at great personal and professional risk. Now, Academy Award-winner Laura Poitras (CITIZENFOUR, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed) and Emmy Award-winner Mark Obenhaus (Steep) have crafted Cover-Up, a documentary that uses Hersh’s remarkable career as a framework to examine the recurring patterns of institutional violence, governmental deception, and the cycles of impunity that define American power.

Poitras first approached Hersh about making this film over twenty years ago. He declined, citing source protection concerns, but they remained in contact. That patience has paid off with extraordinary access: the filmmakers were granted entry into Hersh’s legendary archive of notes, files, and documents.Together, the co-directors have constructed something far more ambitious than a conventional biography, they’ve made a film that traces how lies told in Vietnam echo through Watergate, through Chile, through Iraq, and into the present day with Gaza.

Cover-Up premiered at the 82nd Venice International Film Festival before playing at Telluride, Toronto, and the New York Film Festival while earning five Cinema Eye Honors nominations and an IDA Documentary Award nomination for Best Production. This Praxis Films and Plan B production arrives in select theaters in December before streaming on Netflix December 26. It was an honor to speak with Poitras and Obenhaus in the following conversation was conducted separately and edited for length and clarity.

LAURA POITRAS

Hammer to Nail: You’ve spoken about being obsessed with Sy Hersh. What was it about his work, specifically, beyond the obvious significance of his scoops, that made you pursue him for two decades? How did that long courtship shape the film you ultimately made?

Laura Poitras: The obsession was driven by a number of things. Obviously, his body of work speaks for itself. But I think more than that was his consistently outsider status, even when he was inside news-gathering institutions like The New Yorker or The New York Times. He was consistently providing different narratives than what the government was providing. In the realm of national security reporting, that’s very rare.

I thought that was essential, particularly because of how vitally important investigative journalism is to a free society. We need to have hard questions asked at the right time—not retrospectively. We can all sit around and agree that the Iraq war was a catastrophe and the Vietnam war was a catastrophe, but who was saying it in real time? And not just saying it, but showing the facts. That’s what’s really important about Sy, his greatest reporting is empirical, it’s fact-driven.

He’s a bit of a punk, a bit of an outsider. I like those types of people. They don’t always make friends, but he’s done such essential work in terms of changing the consciousness of this country. So I was obsessed. But it was also meeting him. I knew his work going in, but he’s great. He’s funny. He’s difficult. He’s unpredictable. All those things that make him a great character for a film.

HiN: You share editing credit on this film alongside Amy Foote and Peter Bowman. You’ve said some sections you loved and spent months on didn’t make the final cut. What was one of the hardest to leave on the cutting room floor? And can you talk about the editing process, finding the language of the film with them? Was the political thriller always a north star in terms of tone?

LP: To start with the political thriller piece, that was always part of the vocabulary of the film. We wanted something that riffs off of films like Alan Pakula’s All the President’s Men and The Parallax View, which are themselves riffing off the dark society they’re about.

It’s always important, I think, as a nonfiction filmmaker to say that yes, I do use some of the tools of fiction filmmaking in terms of creating mood and suspense. But from my perspective, it’s trying to capture what’s happening in the real world. There’s often a hidden menace in these types of films, also in Cover-Up, also in one of my previous films, Citizenfour. How do you capture that sense of dread and fear? So there were always conversations about the seventies as one of the reference points.

Filmmaker Laura Poitras

In terms of the editing, we worked incredibly closely with both Amy and Peter, and also with our archival producer/producer on the film, Olivia Streisand. I felt really strongly that the film would be driven by where we had the archival material to support the storytelling. Some of that was unknown, where we would have great footage that would also allow us to do cinematic storytelling that would be scene-driven.

Going back to your question about scenes that break my heart, that I spent a lot of time editing, really a lot of time, Sy, after quitting the AP, joined the presidential campaign of Eugene McCarthy as a press secretary and speechwriter. He did that out of a sense of despair about the Vietnam War, feeling that was a way he could contribute. They went from being nowhere in the polls to McCarthy coming in a close second in New Hampshire. It was amazing to see Sy move into the realm of politics briefly. He was very good at it, but then hated it and quit. He actually quit over a scandal because McCarthy compromised around not campaigning in the Black community in Wisconsin. It was on the front page of The New York Times that Sy Hersh quit the McCarthy campaign, along with his colleague Mary Louise Oates. I love the story. We had great footage. Paul Newman was in it because he was also campaigning. It’s a great subplot. But in the film, which we were committed to making a single feature, it felt like it was on a different theme. The danger in the edit is making it “and this, and this, and this.” We had to make choices that would align with our thematic interests, and we had to say goodbye to some things we loved.

Another one I loved that we spent a lot of time editing was Sy’s book The Samson Option, which looks at Israel’s nuclear program and how that came into being. We also spent a lot of time on his story about the killing of Osama bin Laden. We didn’t want to say no to anything too early, so we kept a lot in the mix. Ultimately, we had to part ways with some great reporting and storylines to make the themes we were interested in crystallize. Those themes being abuse of power, violence, cycles of impunity, lies, cover-ups, and the relationship between investigative journalism to hopefully put an end to some of that cycle. That’s why the beginning is the chemical-biological story. It tells the whole film in two minutes, in a way that gets repeated.

HtN: Thematic throughlines aside, I hope one day I can see the hundred-hour cut. At the 25-minute mark, we have this section about Paul Meadlo. Sy says he will never forget what Paul’s mother said to him: “I sent them a good boy and they sent me back a murderer.” Why was it important for you to include this moment? And what about that very simple statement do you think really stuck with Sy all these years?

LP: I knew that was going to be in. I love when he says, “just get out of the way of the story.” My Lai and Abu Ghraib were always going to be two pillars of the structure of the film, along with the CIA. They say something really devastating about this country.

That particular section on My Lai was important for a number of reasons. I think people haven’t really been held accountable. Yes, Calley was charged, but not the people who created those conditions. But it was also Sy’s obsession with the story. He didn’t just break the story that there was a massacre. His obsession was: How is it possible? How could these kids, who come from rural areas commit this horrible atrocity? He couldn’t understand what happened that made that possible. What were the structural reasons? So that’s why he kept interviewing. At some point, he had the story. But what he didn’t have was: How is it possible? What were the conditions that created it?

What he learned is the larger cover-up, that they were trying to get body counts, and that was victory. They were instructed to kill civilians, to slaughter civilians. A theme throughout the film is the power of legacy journalism. How It can change the outcome of a war or how we understand a war, and when it doesn’t. This country is very good at forgetting our history. I wanted to return to this history and hopefully reach young people with it. Amy, Peter and I spoke a lot about how we could make the film a process film. With My Lai, the audience only knows what Sy knows at the point he’s explaining the story. You don’t feel the full scale of it until later.

A still from COVER UP

HtN: There are a few scenes where Sy takes a call from an anonymous source in Gaza during your interview. The first happens at around the 38 minute mark and it stays at the forefront of your mind the rest of the film. One of the lines that stuck with me is: “I don’t have the privilege of not believing something can be done because I’m in touch with friends and loved ones.” Can you discuss your decision to include these brief moments?

LP: First of all, it was done with complete consent. To me, it’s essential in terms of understanding Sy and his moral compass in terms of how he reports. There’s absolutely a through line between Vietnam, Iraq, and Gaza. We wanted to make that connection.

It comes right after the My Lai story. The source also says that Gaza is the past and the future combined, collapsed—that it’s a precedent. I think that’s very true with what we are seeing there. If a genocide is allowed to go unpunished, then it sets the stage for it to be repeated. That’s what the film is about. If things go unpunished, we set the stage for them to be repeated.

The politics of despair are not acceptable when people are dying in real time. They’re just not acceptable. That’s what we wanted to say with that scene. Yes, I think we all feel despair, but we cannot give up on people. She’s saying that from a very personal perspective. I think that’s something we all need to understand: we create history every day, by our action or inaction. That was something we talked about often in the edit. How do we tell the story in a way that doesn’t present history as being inevitable?

HtN: At the 58-minute mark, we get this portion about Kissinger, Allende, and Pinochet. To start it off, Sy says that Kissinger and his group would do anything to stay in power, any lie, any story, bury anybody. Sounds pretty familiar…can you talk about crafting this section?

LP: The main editor on that section was Peter Bowman. He worked on establishing Kissinger. With the archival material, we really wanted to set up characters, and in this case antagonists, with Kissinger being the key one.

Chile was so important to include because Sy did so much reporting on it. It also represents so much of the U.S. government’s international interference in promoting dictators around the world, either supporting coups or in other ways. Chile represents both that specific story and the larger pattern. There are things we think are very haunting for today, the rounding up of dissidents. We’re seeing people being rounded up all over the world today. We wanted to make that connection.

HtN: At the hour and 25-minute mark, you and Sy have a back-and-forth about him being criticized for using one source. You say it’s legitimate criticism. He says, “Even if it’s nine sources, sometimes it’s best to make it one.” You push back by saying, “What if you have one source and it’s wrong?” He says, “That means I have 20 years of working with a guy that I’ve been wrong on.” Can you talk about how this approach makes Sy who he is?

LP: I’m not going to talk too much about Sy—I think only Sy can talk about his reporting, however, we had an obligation to voice our skepticism when we had it. I definitely had skepticism around that, and I think it’s a dangerous practice. We wanted to include that.

When I did the Snowden reporting, when I was first contacted, you have to run through your mind: are you as a journalist being played? Are you being set up by, for instance, the FBI? Are you being fed something to advance some other agenda? Does your source have only partial knowledge? Those are all the things you ask yourself, and I think they’re just as important.

Sy’s reporting on that particular story, the Nord Stream story, has not been corroborated by other journalists. In fact, they’ve reported different facts in terms of what happened. So it was important to include that skepticism.

HtN: You’ve said that when you were setting up cameras in Camille Lo Sapio’s home, she finally told her husband why you were there. Can you describe what that moment was like? Witnessing someone revealing a 20-year secret to their spouse with cameras present? How did you first learn about her, and what was the process of convincing her to come forward?

LP: Sy had spoken about giving his number over the radio, so I knew that story. But when I first asked him, his response was, “No way, this is my source.” He had an unsurprising reaction, “I’m not going to give you my sources.” But at some point, he understood it would be interesting for the film and that I was not competing with him. He was protective of her, but once she agreed, we got there, and she was telling her husband. She said, “I need to tell my husband why you’re here.”

He was totally supportive, but it speaks to the very real fear that she had, and that sources have when they speak to a journalist. She has everything to lose and nothing to gain. Unfortunately, what we see over and over is that it’s not the people who torture in the government who are punished. It’s the whistleblowers, the sources who expose the wrongdoing.

She was really worried that something would happen to her by sharing these photos. He was totally understanding—I think he probably had huge respect for her.

MARK OBENHAUS

Hammer to Nail: You first collaborated with Sy in 1985 on the Frontline documentary Buying the Bomb. Can you talk about how your relationship has evolved over the past 40 years, how you met, and what your friendship really looks like?

Mark Obenhaus: We were introduced by David Fanning, the executive producer of the PBS series Frontline. I had made a number of films for them from the start of the program in 1982. He said, “Why don’t you go meet Sy, and maybe you’ll have something you want to do together.” So I went to Washington, to his office—this legendary space stacked with lots of files, books, and so forth. I think we hit it off. We had some family connections, actually. I’m from Chicago as well.

The story that appealed to me a lot was what he was diving into at that point—researching this person named Vaid, a Pakistani national who was allegedly attempting to export triggers for nuclear bombs, specifically called Krytrons. The case had floundered around in the Justice Department without much enthusiasm. At that point, there was still controversy over whether Pakistan was attempting to build a bomb.

Mark Obenhaus

We started chasing the story, and it exposed me to the wonderful way in which he goes about reporting. That is to hit the ground running, go from place to place, person to person, and develop a case. Indeed, we came to a point in the film where literally he says, “I think this is the smoking gun.” I think we proved exactly who he was and what he was doing.

It was a very exciting experience. I was at that point shooting all my own films, and it was a vérité film in the main. It’s a really good film—it stands up. You see Sy in all of his methods, talking to dozens of people, digging into records. It exposed me to Sy’s methodology. I enjoyed the experience tremendously, and we went on to make a few other films and remained friends ever since. A lot of the footage from Buying the Bomb you see in Cover-Up. All the footage of him walking through streets, up stairs, etc is from the film.

HtN: Your background includes major network documentaries for ABC, PBS, Discovery. How did working with Laura differ from your previous collaborations? How did you divide directing responsibilities? Were there specific sections or aspects of the film that you each took the lead on?

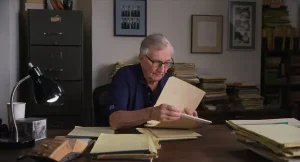

MO: It’s a fairly organic process. The center of it was the interview experience with Seymour. That interview is the through line for the whole film. That’s a product of many different sessions interviewing Sy over months and months. I hesitate to guess, but I’m sure there’s close to 100 hours of interviews with him. We would say, “Okay, this trip, we’re going to Washington and we’re going to talk about X story or Y story.” We would have a finite agenda.

The most remarkable production aspect of the film is that we shot the interview with three cameras—two frontal and one from the side. We actually had four cameras operating because we also had a pedestal camera set up in an adjoining room where we could photograph documents. The unique aspect of this production was that the archive supporting the interviews and the entire documentary was on-site. Sy’s notes, his records. We were given access to those records.

We had a wonderful archival producer, Olivia Streisand, who had the daunting task of organizing and making sense out of these files. She was able to provide us with notes or documents while we were doing the interview that were provocative, that provoked Sy. It was, in my experience, a completely unique environment.

Both Laura and I asked questions, and at some point, other people in the crew asked questions as well. That environment was really the foundation of the film. The structure is largely chronological, so the editing process was one of deciding what to include, what to eliminate. We had agreed we’d have a film about two hours long. We didn’t want to make a longer film. There was a real process of elimination because there are many more stories from small to large that could have been included. Normally you would have to say, “we will come back to that when we have all these documents etc,” but they were all there. We had this brilliant archivist organizing them in a way that had never been organized before.

HtN: Sy’s notes are famously unintelligible.

MO: Yes, famously so. Even AI couldn’t penetrate his handwriting.

HtN: We also see that side camera in the sequence where Sy quits, and he becomes more combative and even paranoid as the film progresses. How did you handle moments when he was skeptical of your motives? Can we talk specifically about that moment where he quits?

MO: To contextualize it a little, though it is a dramatic moment in the film, it happened maybe two-thirds of the way through. We did not panic. Sy’s a volatile character. I’m very aware of that. He’s capable of outbursts of various kinds. I thought things would calm down.

What happened was I drove to his house shortly after and arrived there. He was in the living room. I said, “I know, I know, I know.” And he said, “I’m over it, and we’ll go back.” Then he says something he said to me there, but he also says on camera: “I committed to start this thing, and I will follow through on it.”

Though he expresses some skepticism about us, I’ve known him an awfully long time, and I think he had a lot of faith in my integrity and judgment. Similarly, he grew to have that for Laura. It was part of witnessing his personality. I don’t think it was ever really a threat to quit the film. I think it was an outburst, which is how it appears.

HtN: Those outbursts are well documented in the film as part of who he is. Sy’s parents were Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants from Lithuania and Poland, and we explore that around the 40-minute mark. How did exploring his family’s immigrant background and the silence in his household illuminate his journalism for you? Was that part of him something you were aware of?

MO: Very much so. But I think it was something he was uncomfortable talking about on film or in public. But people who know him well know much of that history, and I certainly did. It was always our intention that this would be an aspect of the film.

I’m from Chicago. I grew up not far from where he lived and where his father’s store was. He actually, at one point when I was in high school, lived in a building next door to me. So I have a picture of what that world he describes was like, and some sense of what his life was like in his family.

He wasn’t comfortable talking about it initially, but he knew we were doing this film and we had to probe him. Eventually, as you can see, he becomes somewhat comfortable talking about it. I think it’s extremely important. There’s a lot to glean from his experience within his family.

One note I should mention: he did write a memoir, Reporter, which was published some years ago before we started this project. He’s pretty frank in that book about his life. We were greatly benefited by that book—we didn’t option it, it’s not based on that book—but what it did was force Sy, when he was writing it, to re-examine his whole career. He had to relive it to write that book. So our timing was fortuitous that he had done that a couple of years before. His memories were pretty fresh.

HtN: Sy isn’t the only person you speak to in the film. One of the outside sources is Major General Antonio Taguba, author of the Abu Ghraib investigation report. This is such a riveting portion of the film. Can you talk about working with him?

MO: Tony is somebody I’ve known for quite a while now—at least five years, maybe more. Sy introduced me to him, but we’ve had lunch many times. He’s a real believer in the military, in the Constitution, in telling the truth. I find that incredibly inspiring.

It points to something Sy frequently says, that the military, which he’s covered extensively for 60 years, is full of people with a lot of integrity. Tony would be one of them. Since the initial report, Sy wrote a profile of General Taguba in The New Yorker, and I think they’ve become very good friends. I consider Tony a friend, and I have enormous respect for him.

He was basically kicked out of the Army, in effect. That’s a simplistic way of explaining it, but he was denied his third star because Rumsfeld thought he had leaked the report, which he had not. One of the things I was very satisfied by in the film is that we were able to make clear that Sy got the report from someone other than General Taguba. He got it from an attorney who was defending a person accused of crimes associated with Abu Ghraib. The attorney had been given the Taguba report as part of evidence, and he gave it to Sy. Tony didn’t leak it. The last thing Tony would do is leak a report. He’s a person who follows the law.

It has infuriated him that people in the military viewed him skeptically at the time, when he had great integrity.

HtN: At the hour and 24-minute mark, Amy Davidson Sorkin talks about the JFK letters as a cautionary tale about journalism, but also about Sy’s strengths and things that are not necessarily his strengths. What exactly do you think she means? What was the weakness she was implying?

MO: Specifically, she was saying that he had accepted what’s called the Cusack papers, and he had started to ask a lot of questions about them. As he explains, he was very interested in them. They suggested a relationship nobody knew about between President Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe. Anyone writing a book about John Kennedy would go, “Wait, if this is true, it’s a bombshell.”

His embrace of them initially was logical, but I think she’s maybe saying he didn’t have enough skepticism. I can say that because I can claim the responsibility for uncovering them and determining they were a fraud.

It was more complicated than people might know. These papers had been selling for millions of dollars to various people on a hidden memorabilia market. There were four or five handwriting experts who had deemed them legitimate, including this guy Hamilton, who was the most revered.

So there was some initial support for their credibility. But it took a while for us to break it down. We determined there was a typeface allegedly on one of these letters that didn’t exist in the year the paper was dated. Eventually, an FBI agent I hired really tore it all apart, and the whole house of cards fell down.

I’m an insider on that, and I have to give it a bit of a pass because I was aware of how much—if I may say—bullshit was out there, disseminated by authoritative people used by major libraries, saying the papers were good. We persisted and found they weren’t. In her view, maybe it should have gone more quickly. That’s legitimate. But we were doing a lot of other things—we weren’t just making a film about those papers. We were making a film about Secret Service agents and dozens of other subjects.

If you’re Sy Hersh, you’re a target. You’re the hotshot guy, and you’re not supposed to make mistakes. Well, you do make mistakes. Everybody makes mistakes.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)