A Conversation with Richard Linklater (NOUVELLE VAGUE)

Richard Linklater’s career has been marked by great experimentation and variety, which makes him the perfect candidate to dramatize one of the seminal moments in film history: the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s French New Wave masterpiece Breathless. Starring a mostly unknown group of young French actors—and one American star, Zoey Deutch—Nouvelle Vague chronicles its main character’s impish, arrogant, and wildly brilliant approach to filmmaking. The result is a movie that is as playful as one could wish, in celebration of the joy of cinematic creation. I saw the film at the 2025 Middleburg Film Festival (where I reviewed it), and then shortly afterwards spoke with Linklater by Zoom. What follows is a transcript of that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Hammer to Nail: You write in the press notes that any filmmaker who has been working for a while should, at some point in their career, make a film about the process of making a film. Seems like a fair point, but there are plenty of folks who haven’t done that. You’ve been making films for a good long while. What did you learn about filmmaking while making Nouvelle Vague?

Richard Linklater: Well, I said that kind of glibly, but every film is its own dramatic production. You could probably make a film about the making of every film. But I didn’t really want to make a film about my own experiences so much. It was more interesting to me to jump into the history of a film, and not just the film itself, but a time and place. The Nouvelle Vague movement is so influential. It means so much to world cinema and it’s just such a confluence of great films and great filmmakers all in one place. It hadn’t really happened that way before. It’s probably the closest cinema ever came to punk rock.

It’s a movement that was famous in its day. Normally, no one appreciates what they’re doing while it’s going on, but the Nouvelle Vague was famous at that very moment and well-documented, which helped when it comes time to recreating it all. We got all those photos and everything to build it out from there. But what I learned was that my respect for Breathless and what Godard achieved is even more impressive and more mysterious. I know more about that film than anyone deserves to. I know how many takes they did. I know what lens they used on every shot. I know everything. But how it works is still about [Jean-Paul] Belmondo and [Jean] Seberg, something Godard conjured, something really special. And this genre mashup—of time, place, energy, new language, modernism—makes it a real modernist work. So I don’t know. It is a fun film. I’m not even saying that it’s my favorite Nouvelle Vague film. I’m just saying it’s an interesting touchstone.

HtN: Absolutely. I saw the film at the recent Middleburg Film Festival, where Zoey Deutsch was in attendance and she mentioned in the Q&A that you don’t speak French, which blew my mind. Is this true? That must have made shooting, not to mention writing, quite the challenge. How did you manage those challenges?

RL: The script was in English and we translated it, but the language wasn’t even a barrier. It wasn’t in the Top 10 of my concerns. It really wasn’t. I was so strangely confident in how this could work. And my French producers totally got aboard. And English, for better or worse, is everybody’s second language. So everybody I’m working with, they’re understanding, I like to think, 85/90% of what I’m saying, and we would rehearse in English and then we would jump to French.

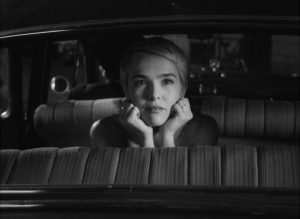

Zoey Deutch as Jean Seberg in NOUVELLE VAGUE

And I’m making, in my cinematic brain, a black-and-white subtitled movie, a French movie with English subtitles, the way all these films came to me when I was falling in love with cinema in my early twenties. This is what these films looked and sounded like. So I’m just replicating that. I’m like a musician who goes back into an old studio with old mics and old tube amps and gets an older sound.

HtN: It just makes it all the more impressive to me that you did that. So, almost everyone in this film is a relative unknown, though Deutch is obviously not. You worked with her on Everybody Wants Some!! in 2016. Why did you want her for the role of Jean Seberg? What did you see? She said that you approached her, that you worked together before and you had seen something in her. What was it?

RL: Well, she had the resemblance right there in her face around the cheekbones, and I said, “You could pull off Jean Seberg.” And we were already embarking on the idea of making this film all those years ago. And I said, “Hey, I’m going to do this film and you’re going to play Jean Seberg. How’s your French?” And she says, “Oh, I don’t know.” And I said, “Good. Seberg was learning French at the time. You’ll be doing that, too.” And she jumped in. Man, she worked so hard. It’s kind of unbelievable what she had to do. I mean, cutting her hair and getting that look is just a little part of it. Everything else was pretty rigorous.

But she was the perfect analog to Seberg. She was an established actor coming in from the United States, dropping into a French film production with relatively all unknowns and lesser-known people in that situation. But the difference was she was very comfortable, while Seberg was put off, and why wouldn’t she be? Godard won’t tell her much about what the film even means or who her character is and has no script to show her. So Jean was as brave then as she ever was to kind of persist through that. And I think Belmondo kept things kind of fun for her, but it was an off-putting, irritating experience to whatever degree that Godard had a way of doing to his actors, both male and female, by the way.

HtN: He comes across here very much as this creative, playful, but also somewhat arrogant imp, shall we say.

Guillaume Marbeck as Jean Luc Godard and Aubry Dullin as Jean-paul Belmondo in NOUVELLE VAGUE

RL: It’s fair to laugh at Godard. I say this out of all respect; he’s a funny character. People say, “Why’d you do this film and not any of the others?” It’s like, “Well, he’s funny, the comedic character, he’s so different. He’s so strange. His use of language, he inverts things. He always has a funny quote. And he’s masking God-knows-what insecurities underneath all of his bravado.” So it’s fair to laugh either at or with him.

HtN: And I think you do both. And Guillaume Marbeck is so terrific in that part. And Aubry Dullin is so great as Belmondo. How did you find them? They’re really perfect. Not only do they resemble the characters, but they’re excellent, excellent actors.

RL: Yeah, people talk about the resemblance and that’s certainly a part of it, but you’re casting an actor. Everybody’s different. Aubry comes in and he had this kind of quick smile and ease to him. A lot of young French actors, they’re more serious. They love Belmondo: “Oh, he’s an icon. He’s my favorite.” And I’m like, “Noooo.” Aubry comes in and says, “Yeah, I’ve heard the name, but I have never seen Breathless.“ He’s just kind of loose. I’m like, “You are Belmondo. You are. You don’t give a shit. You have this kind of cool ease to you. That’s so Belmondo-esque.”

And same with Guillaume as Godard. He had this little swagger to him, even though he’d never made a film. He was just some guy in his late twenties, but he had this kind of confidence in himself. I call it the “unearned swagger and confidence of a first-time filmmaker.” (laughs) I recognized it. He thinks differently. He’s funny in an odd way. And I was like, “God, you’re just quirky enough and just funny enough.” So you know, when you see it, you go through hundreds of people, but it’s love at first sight when you do meet them. And that goes for the guy who played Truffaut, all those—Melville and Bresson—you work through everybody. You’re trying very hard to get it right.

HtN: Speaking of all those characters, you present them on screen with these short shots where they stare into the camera and their character names—not the actor names—appear beneath them as they stare at the camera. What made you land on that approach?

RL: I was wondering, as we got closer, how anyone was going to know who anybody was. You don’t say, “Hey, Claude Chabrol, what are you doing?” And I’d never seen that before where you get introduced before your first scene, just staring at the camera. It seemed like a Nouvelle Vague kind of conceit. And I also wanted to place them on some kind of level playing field of historical importance or presence, maybe. All these people, ranging from Jean Cocteau to José Bénazéraf—the sleazy car dealer who ends up some kind of porn dealer—they’re all alive at this place in time, and they’re all in our movie for a reason; they’re all swirling and breathing the same air. And some of them are pretty obscure characters but at that time, they’re all part of the same culture. And I just thought this movie about the film culture of that time and the film crew, it really honors the people who work on films: the assistant directors, the assistant camera, the set photographers, the script supervisors. I love the people who do this for a living. They’re pirates; they want to do this. And so it was a kind of a tribute to their efforts.

HtN: Without them, films wouldn’t get made. In terms of techniques, I love how you repeat the reflection in Godard’s ubiquitous sunglasses at the end. When you first use the shot, it’s to show the final moment of Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, and then we end with that shot of Jean Seberg in his glasses, as well. And of course, the sunglasses are kind of his armor against the world. They’re always on. So how did you decide to repeat that shot through the sunglasses?

RL: Well, not only are they two famous endings for probably the two most famous Nouvelle Vague movies, but it bookends the movie: Truffaut first and then Godard, with those ubiquitous shades that never came off. They were prescription, by the way. It wasn’t all show. But yeah, he’s one of the most famous sunglass-wearers in history. We had to play with the iconography.

HtN: Absolutely. It’s such a great shot. And speaking of that, you and your cinematographer, David Chambille, do such wonderful visual work here. What specific guidelines did you give him to work with for the film?

RL: How about this guideline? This film was made in 1959 using the materials of the day with the language of the time. And I said, “We’re going to make this film like it was shot then. We’re going to forget everything after 1959, all innovations and technologies, we’re going to make it look like it would have back then.” And he was so up for it. He said, “Raoul Coutard is my favorite cameraman.” And we were finishing each other’s sentences, the first meeting we had. So it was just a lot of tests to get that look and feel. And that doesn’t usually work in film, to kind of recreate that, but we were determined and we thought it would work for this movie, and we had a really great time doing it. It was really, really fun to study this era and try to get that right. Ideally, not one shot in this movie wouldn’t fit into a film of that era.

Guillaume Marbeck as Jean Luc Godard in NOUVELLE VAGUE

HtN: The infectiousness of whatever you’re doing comes across. Not only is the cast having a great time, but you can tell that most likely you and your crew are, as well, as you recreate this era of Breathless. So, were there any specific spots in Paris where you just couldn’t photograph it the way you might’ve wanted to because the city has changed? Fortunately, there are parts of Paris that really haven’t changed all that much, but there must have been some locations where you couldn’t just do that.

RL: For a major urban city, I would say Paris is preserved better than almost all others. It’s just that on the first floor, on the ground level, there’s going to be commercial space where there was a café, there’s now a motorcycle shop, etc. So that all has to be dealt with. We had to basically do everything they didn’t have to do back then. They could just show up and shoot; they were practically a student film. No one knew they were making a movie, whereas we had to go back and replicate those locations from that time. And sometimes we got lucky. We just used the real locations that were very much like they were, with maybe little adjustments.

But then the Champs-Élysées with The New York Herald Tribune, if you go there to that exact spot, you wouldn’t recognize it. They’ve paved over it and widened the sidewalk to include that little mini-road right before the big road where the scene takes place. But if you go 180 degrees on the other side of the Arc de Triomphe, there’s a big street heading out of Paris called the La Grande Armée. And that does look like the period piece. So it worked perfectly, but we’re 180 degrees on the other side of the Arc; you just make it work. The hotel is no longer where it was, but we built that set. That was one of the few sets we built.

HtN: I am obviously a cinephile and I love the French New Wave. You didn’t have to convince me to see this movie. I’m in. But what would you say to people for whom that knowledge isn’t there or that initial desire isn’t there? Why should they come see this film? How would you pitch it to them?

RL: It’s been fun for young people who are just getting into cinema. On the simplest narrative level, it’s not confusing. It’s a bunch of young people who come together to put on a show, conflicts and things happen, and it’s over. So there’s nothing confusing about it. A teenager has no problem getting the story. Now there’s another level if you want to get into the history and what it all means. I’m really making this for my younger self. Back then, I couldn’t wait. There was this big adult world with references and adult-themed concerns happening and I was getting there, but I didn’t quite understand it, but I couldn’t wait to get there. And you can really do your research and find out so much and see these rich worlds that have existed and that do exist.

Everybody’s different. I think for certain people, culture and art history are going to be a big part of their lives. You can make a life about art; a lot of us have. And it’s exciting to see young people create. I remember thinking that way in School of Rock. I just wanted to make it look cool to be in a band, to make music with your friends. That just looks like a worthwhile thing to do with your time. And I think the same here: it’s fun to make a movie if that’s how your brain works and you feel you should get your friends together and make a movie and just see how that goes. It’s really fun if that’s what you’re meant to be doing. It’s just young people putting on a show. That’s the basics of it. But then it’s obviously this rich history, if you want to dig into that, too. I like how art can work on various levels. There’s nothing obscure about the movie, but it is in black-and-white; it’s in French with subtitles. But I remember that being super cool to me. At a certain point, it’s like, “Oh, wow. Yeah, I’m not just this hick from Texas. I like French films.”

HtN: Well, I love the film. Thank you so much for talking to me.

RL: Thank you.

– Christopher Llewellyn Reed (@ChrisReedFilm)