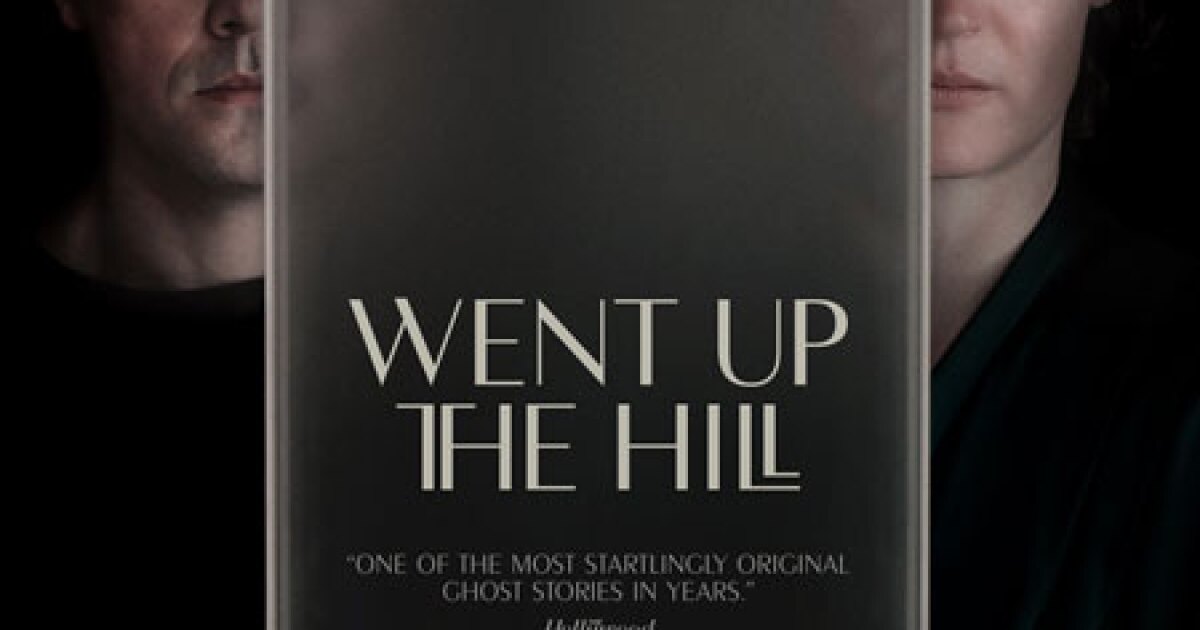

A Conversation with Vicky Krieps & Samuel Van Grinsven (WENT UP THE HILL)

Went Up the Hill is a haunting psychological supernatural drama that explores the complex aftermath of grief and trauma. Directed by Samuel Van Grinsven, the film follows Jack (Dacre Montgomery), who travels to remote New Zealand for his estranged mother Elizabeth’s funeral, where he meets her widow Jill (Vicky Krieps). Over several nights, Elizabeth’s spirit begins possessing both Jack and Jill, forcing them to confront deep-seated wounds and the toxic legacy of loss. Set against the atmospheric backdrop of New Zealand’s South Island, this modern ghost story examines how we carry the ghosts of our past relationships and the struggle to break free from cycles of trauma.

Vicky Krieps, the acclaimed Luxembourg actress known for her powerhouse performances in Phantom Thread and Corsage, brings her fearless approach to the complex role of Jill, Elizabeth’s grieving widow who must navigate both her own trauma and the arrival of a stranger claiming to be her wife’s son. Samuel Van Grinsven, the Australian/New Zealand writer-director whose debut Sequin in a Blue Room garnered critical acclaim at the Sydney Film Festival, crafts an intimate chamber piece that strips away conventional horror tropes in favor of raw emotional truth. Together, they’ve created a film that challenges audiences to confront uncomfortable questions about love, control, and the ways we’re haunted by those we’ve lost.

Vicky Krieps

Hammer To Nail: The film poses the unique challenge of playing both Jill and Elizabeth through these possession sequences. How did you and Dacre develop a shared language for portraying that same spirit?

Vicky Krieps: Dacre was on board first, and then I got the script. I liked the idea of the challenge of being two actors playing three characters and the trauma through ghosts and all of that. But there was something originally in the film that I didn’t like. A supernatural element. There was this scarf that was used to indicate who had become the ghost. It was initially going to be done with CGI. I read the script and liked it, but I didn’t feel the scarf because it felt like a missed opportunity of really trying something through acting.

So I dared to voice that and that’s why I’m executive producer too. I said, “What if we remove the scarf? I have a feeling the scarf is too much and also the scarf is hiding something that could be even more if we dare to just go there.” And they agreed. Then we had no scarf and I was scared that I made a mistake and that everyone would hate me if it didn’t work.

How do you become the other person visually for the audience if you don’t have anything else to tell them but your face. Starting that journey together with Dacre, we noticed that the less we do, the better. It takes a lot of courage to say, “I’m not doing a mimic. I’m not changing my voice. I’m not changing my body.” Because of course these are things that help you as an actor become another person. To really dare to be so naked and try to become another person just by shifting your internal energy. To trust that is really not easy. For me and Dacre, it was both a journey of trust and letting go more and more, like stripping down more and more.

HTN: The house itself becomes almost a character representing Elizabeth’s control. How did filming in that specific location affect your performance?

VK: It was very oppressive. It was very claustrophobic. It was dark and eerie. We were always in that house. Either I was on one side or he was on the other side, but we were never really far away from each other. It was so oppressive and intense. I think the house played a big role in this intensity. As soon as we got out of the house, we just ran away from each other, which is funny because normally you hang out when you make a movie and make friends. On this movie, me and Dacre just disappeared. I went to the forest and walked. I have no idea what he was doing. He does not know what I did. We didn’t even text. It was very surprising and peculiar, but I think it was just a natural reaction we both had to this intensity that was a mix of the house and the story and the psychology. It was always on us. We were always naked, there was nothing.

HTN: You said in the press notes that you thought something happened to you guys like it had been an enchantment and that the voodoo feeling was very strong. Can you elaborate on what made this particular production feel so spiritually charged?

VK: What the film talks about is very true. We live and think we are free, but we are all possessed by our past. Whatever we’ve gone through in past relationships will go into the next one. Whatever someone did to us remains and we project it onto the next person. So we are all not that free and really charged with our past, and in that sense, almost like carrying these ghosts or possessed by the ghosts. We need to break free. That’s how you get over trauma, that’s how you heal from trauma. It’s really about how you break the cycle and heal family trauma, your own trauma, ancient trauma. That is really what the film is about.

Vicky Krieps in WENT UP THE HILL

I think because what it talks about is so true and deep, it did feel like a voodoo thing. Because me and Dacre both brought our personal private baggage and put it in there and made it very personal. So even if it was acting and it was a performance, it felt personal all the time.

HTN: The rehearsal process involved recreating moments from Elizabeth’s past that don’t appear on screen. How did that shared history building affect the final performance?

VK: We worked with Polly Bennett, the choreographer, and she worked with us on energy and body work. This was mainly establishing what was the relationship of Jill and Elizabeth? How did that feel? If one is Elizabeth and the other is Jill, what was their relationship? How abusive, aggressive and dark it was? The same thing happened, it was almost too intense and we didn’t go through with it completely. We had a few sessions, but it became so dark so soon. This woman was just so sick, dark and mean that neither me nor Dacre felt like we wanted to be around it much longer than we had to.

What we recreated was how they met. How did they meet? If they met, what would have been their dynamic? What is it that she liked in the other? That was super nice to do.

HTN: I love this sequence at around the 20 minute mark where Jack touches Jill as Elizabeth. You are sleeping and when you wake up and feel the hand in a great feat of acting you very subtly relay to the audience, before even saying it, that the hand feels like Elizabeth. This leads into a riveting back and forth where Jack as Elizabeth explains why she needs Jack to stay around. Exchanges like “I thought it would stop” “did it stop” “no the pain just follows.” or “where are you when you are not here” “im alone” “me to” have really stuck with me. This then leads to that first kiss. Can you just talk about what was important to you here?

VK: Some people brought up that first kiss, and it’s interesting because they asked me, “If there was a scarf in the beginning, how would that have worked?” The kiss was there, but it would never have been the same. When people say that, I’m like, “Okay, yes, it was the right thing to take the scarf away.”

I think Dacre and I are both actors who, when we go to work, when we show up, we forget everything we came from. It’s just all about that one moment. It’s really two people making themselves 100% available to the script and to the moment and to the exchange. It’s like a theater play, like an agreement. “You are this guy, okay, then I become this one, and then this is what we do, okay, let’s go.” If two people really agree to something that much, then it becomes real. I think that’s what it is. It feels real looking at it, and it felt real in the moment. All the scenes felt very real because I think he is like me, someone who puts everything into it. There’s no going on your phone, you are really gone.

HTN: I love the sequence at the hour mark where as Elizabeth, you run out to the lake. Elizabeth presumably wants Jill to fall into the lake so she can die and hopefully join Elizabeth. The sequence begins with you as Elizabeth, then after Jack explains that he’ll never let Elizabeth go, the two of you faint and the roles are reversed. At this stage, Jack cuts himself with a rock. What was important to you in these moments?

VK: What was important to me, and I think to Dacre too, was that I felt really challenged by this whole idea of fainting and waking up as the other. It wasn’t so easy to trust that. To faint and then become the other – how do you know? Again and again, I think the whole movie was about trusting it and saying, “No, I’m going to trust this. I wake up, I’m Jill. I wake up, I’m Elizabeth,” which is something only I can do.

I think for Dacre, he spoke about it, it was very exhausting for him, physically and mentally. And probably why, and I felt it too, is because you could only do it yourself. There was no dialogue. In reality, there was dialogue, but before the dialogue, you had to already know who you were. And that was something, this journey, only you could do yourself. So me and Dacre, we had to make the journey to be Jill, to be Elizabeth, and speak from that place. It’s like you do double the work.

HTN: Later in the movie, you two wake up in bed and realize that Elizabeth might be gone. You offer to take care of Jack and help him with his flight, saying “it’s no rush, you can stay.” It felt like a maternal instinct kicks in for your character to help this boy/man who has been hurt. But when he touches your face, you subtly relay to the audience that it doesn’t feel like Jack’s hand and you rush away. What was your thinking here?

VK: As Jill, my thinking was what you described, it’s not him. The maternal thing is interesting because that’s something we didn’t speak about much, but I felt it a lot. I think that might have been Jill and Elizabeth’s relationship, that Elizabeth might have been the older one, but the broken one in her love to herself. And Jill might have been the weaker one, but with a more intact heart and love, which is maternal love.

I think this is something Jill always had and could never express. When she sees the child, she has the maternal feelings that Elizabeth could never have for her son. That’s very interesting that you say that because I felt it in the making, not really on paper and nothing we spoke of, but I felt it. And then it turns and that’s really, really sad. I remember being just so sad that it’s not what I thought it was.

HTN: The final moments on the ice are very intense. Elizabeth as Jack makes one last attempt to drag you into death, and your character screams “I’ve let go of you, why won’t you leave us?” Your delivery was incredible. What was important to you at that moment?

VK: That was challenging for me because I have difficulties trusting everything that becomes mechanic. On the ice, it became mechanic because it had to be mechanic, there was obviously a lake, but we weren’t really breaking through ice because otherwise we would have died. So of course that was all made in different pieces.

There was a lake and it was really freezing cold, we were actually freezing to death. That was real. But then they had to build an incredible ice surface. There were guys from Lord of the Rings and they built this ice surface that looks exactly like ice, sounds like ice. When you walk on it, it looks like ice, but it’s not. Then we did all this stuff on the ice there and later in a pool with ice that would break open so we could fall into the water.

All these scenes were very difficult because I had to learn to trust again. I’m an actor, if you leave me alone in a room, I’m not scared of anything. I can just tell you anything and worst case you tell me that was bad acting. But when I have to depend on choreographies or stunts or water, it feels so mechanical. It looks like Ice but it’s not really ice. We have done it many times before so it’s not as natural and there’s 50 people watching me. These scenes I remember in particular that I was very scared that it wouldn’t work. I was really just trying to make it sound real.

HTN: In the press notes, you compared Dacre to Marlon Brando, saying he’s taming his own beast through his work. Can you elaborate on that comparison?

VK: That’s a huge compliment, and I think it’s very accurate. It’s something in his eyes and somewhere between the desperation of coming through into this world, which is almost impossible because our world is a material, plastic world. Some souls reach somewhere else and they try to come through, and some of them become actors. In their acting, their souls come through and break open in their work.

Marlon Brando always had that, he had this soul, maybe tortured soul, that wanted to come through and break open in the acting. But for Dacre it’s different because he lives in a different time. I think it’s that. the soul wanting to come through.

Director Samuel Van Grinsven

HTN: You said that the film began with a single image of two people mourning someone they barely know. How did that image evolve into this complex exploration of possession and control?

Samuel Van Grinsven: I always start in a visual place and then spend the rest of my time trying to figure out where subconsciously the image came from. With this one, I was really interested in the idea of a wound, a family wound. Whether that’s the loss of someone or the rejection of someone, and how you spend the rest of your life trying to fill that wound.

In doing so, people come along who are able to or actively trying to give you everything that absent person could have been. But you’re maybe not awake to it or not aware of it. That naturally led me to the idea of focusing on two strangers who actually become that person, that missing person, in order to heal each other.

Director Samuel Van Grinsven

The nursery rhyme came from that, this idea of something that is passed down from family to children, and is both caring in nature but also cautionary in its content, designed to lull you to sleep. It was a cocktail of all those elements that brewed into this concept of a three-handed story with two actors.

HTN: You worked extensively with cinematographer Tyson Perkins on a visual approach inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s Persona. Can you break down how that influenced your framing choices?

SVG: What’s unique about this film is that we never introduce the audience to the real third character. We don’t give you a lot of her backstory or real visual references. You only get to meet her through Vicky Krieps’ bodily interpretation and Dacre Montgomery’s interpretation. It was really important to me that we brought her to life through every other tool in the toolkit, especially the visual language. That came through in the sense of precision and control and composure.

I think Bergman is really beautiful. Something I’ve always loved about his work is that you learn so much about the world and characters through his camera work. He’s using that genuinely as character insight and storytelling to fill in blanks in the story. Whether that’s the elegance of the way a camera moves, or in Persona especially, this mirroring of repeating the same kind of frame with a different face and juxtaposing those together, that just really made sense with this film. The use of real light and dark and contrasting those was not only inspired by Persona but also Hour of the Wolf.

HTN: You emphasize preparation and precision in your process. How do you balance that control with allowing spontaneous discoveries on set?

SVG: It’s a challenge. I love the precision of the camera work and it was especially important with this film for being able to evoke the presence of this third character, even when she’s not on screen, purely by the way that the severity and strictness of the camera work would make the audience feel.

But the practicality of that on set is tricky. It’s time consuming and finicky in a lighting sense. But it’s also the last thing I want to do as a director is make my actors feel like I’ve trapped them in a box. In the preparation for every scene, I’m constantly trying to make that box feel like a playground for them.

Vicky Krieps is an amazing example of that. She’ll learn the language you’re trying to create, and then she’ll provoke back at you. She’ll understand the frame or the style, and then she’ll say, “Can we do an entire take this time without dialogue, where I’ll do it all physically but I’ll throw myself to the ground this time?” That’s the freedom you try to keep evoking on set, so that the visual language isn’t taking over and you’re not sacrificing performance.

HTN: The location hunt took nearly a year. What made Flock Hill Lodge feel like the right house, and did it shape the final script?

SVG: It was bizarre. It took so long to find. I was really confused because I’m from New Zealand and when I wrote this I was inspired by New Zealand architecture, so I thought we’d find this house quickly. But it ended up being closer to home than I imagined, about an hour and a half from where I was born.

It was extremely eerie in that we walked in and it was identical to the layout we had written. The two bedrooms flowing onto a hallway which flows onto this central living room, all with the same view. It was as isolated as it appears in the film and as it was in the screenplay. But the challenges that came with the location were honestly making it feel smaller than it was, because it is quite big and I wanted this film to feel deeply trapping and intimate. It was constantly about condensing the space as opposed to trying to make it feel grander.

HTN: I love the sequence where Jack touches Jill as Elizabeth, leading to exchanges like “you left me” and “where are you when you’re not here?” What was important to you in these moments?

SVG: That scene is one of my favorites in the film. What was important to me is that maybe more than a conventional approach to a ghost, Elizabeth is very powerful. They come back and they’re able to take over through an act of letting go. These characters give themselves over to her. But Elizabeth comes back and has a fully functional human body and a real grounded earthly presence.

What was important to me is that that’s not true to grief. Had we just let her be completely human, I don’t think it would be very true to what grief feels like. So we applied a limitation to her, which was that she can’t speak unless asked a question. That felt very honest to those first few days and weeks of grief where your memories of a person you’ve just lost are really tangible. You could almost still hear them, almost still see them. The house still smells like them.

Limiting her and what that scene is doing is that Jill is fighting the fact that Elizabeth is here. Jill believes she is there because only Elizabeth could touch Jill like that and physically be there like that, but it’s not enough because you have those limitations.

HTN: I love this sequence at the hour mark where as Elizabeth, Jill runs out to the lake. There’s this incredible shot of Jack chasing after her as the score is just a symphony of breath. Elizabeth presumably in this situation wants Jill to fall into the lake so she can die and hopefully join Elizabeth. The sequence begins with Jill as Elizabeth then after Jack exclaims that he will never let Elizabeth go, the two of them faint and the roles reverse. At this stage, Jack cuts himself with the rock. This whole stretch was so powerful. Talk about what was important to you here?

SVG: The scene was really important in that it’s playing with two different versions of ownership and possession, not possession in a ghostly sense, but the act of owning something. The characters in their dialogue, but then in reverse in their actions, are exploring all the different versions of that.

Jack is saying “I can never let you go.” Elizabeth is responding in the belief that Jack will physically leave the house and therefore she will be forced to let go of Jill. And Jill is somewhere trapped between the two. She understands the damage this is doing, but she is being held onto. There are all these different versions of the same question and theme, and they’re all connecting in this nocturnal dance as she shifts between the two bodies, but three characters.

In a technical sense, it’s probably the fastest portion of the film where we have to lean into the fact that the audience is going to question who is who, when, but providing enough clarity of when Elizabeth is in what body, but also not wanting to spell it out, because that’s part of the excitement and mind fuckery of it. Obviously the other challenge was building and shooting on a frozen lake, which was incredibly difficult.

HTN: You developed Jack’s backstory through poetry with Dacre. How did that creative process influence the final characterization?

SVG: Dacre writes these stream of consciousness pieces in his own life, but he hadn’t done it to prepare a character before. I knew that he did this and I asked him if that’s something we should explore. He loves a long preparation for a film, and I asked the question: “Jack’s an artist, you’re an artist in real life. Is that a way of combining these two identities and maybe allowing you to get out of a headspace of over-intellectualizing and start letting the character sit somewhere deeper?”

Poetry is a good way of doing that. The effect it had is that Dacre was able to really create ownership over the character. I don’t specify a lot of Jack’s backstory or Jill’s backstory in the screenplay. It’s not important to this film, but it is important to their performances. I gave both Vicky and Dacre complete authorship over those backstories and filling in anything that wasn’t on the screenplay. The poetry was Dacre really being able to create a story and backstory for himself that worked specifically for him.

HTN: You collaborated with Jory Anast on the screenplay. How did that creative partnership work? How do you guys divide responsibilities in your writing partnership?

SVG: We don’t divide anything. We’ve been best friends since we were in our teenage years, so we know each other extremely well. And genuinely, when I say we don’t divide anything, I mean that we don’t do any writing apart. We physically sit in front of one screen with one keyboard, and we pass it back and forth. Then we spend a vast majority of the time debating about where to place a comma, or where to place a dash, or where to place a full stop.

What I really love about the way Jory and I approach writing is that it’s like live active editing. I think by the time we actually arrive at a first draft, we’re further along than you typically would be, because everything is constantly being questioned by each other. It just provides more clarity, but also it’s more provocative, which means that you get to the core or the good idea faster.

HTN: You mentioned that the film became stiller during production as dialogue and blocking fell away. Can you elaborate on what you meant by that?

SVG: On the first day of shooting, Dacre and Vicky just naturally fell into speaking as if they were inside a church because of the grandness of the architecture and the opposing nature of the architecture. It has those high vaulted ceilings, but it’s also really heavy. It’s quite an oppressive space to be in, in the way that churches are designed to create a feeling of reverence or respect. They just naturally started talking like that.

I think that was nerves on the first day a little bit, but it was also coupled with genuinely how they were speaking as their characters aloud on screen for the first time. This is how the design and the space was making them feel, it was organic. We just ran with that. It felt so real and true to this film.

The first time I ever took Vicky to the house, about four days out from shooting. It was loosely set up. The couch was there in the living room and Vicky walked in and just curled up into a ball on the couch and became quite emotional. She turned to me and said, “Oh, Jill is just a bird in a cage.” She was responding to the location, and she was so still in that moment because she felt so oppressed by the space, but so trapped and cold and alone.

I always wanted the film to be still but it became even stiller. It’s almost like the pair of them felt they needed permission to speak louder within her house or permission to move through it freely. It was interesting, and it was real they weren’t forcing that.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)