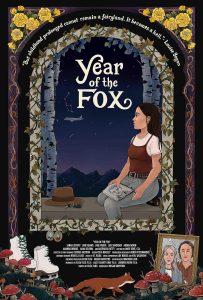

YEAR OF THE FOX

(Check out Jessica Baxter’s Year of the Fox movie review, it’s available on VOD now. Seen it? Join the conversation with HtN on our Letterboxd Page.)

Megan Griffiths’ latest film, Year of the Fox (check out my interview with Griffiths and screenwriter Eliza Flug here) is a coming-of-age drama set in 1997 Seattle and Aspen. On the cusp of high school graduation, a young woman (Sarah Jeffery, TV’s Descendants), adopted into the upper echelon, gets a disillusioning peek behind the curtain of adulthood. There, she finds selfishness, pettiness, a ring of predators and the people who protect them. Year of the Fox presents a complex tableau of American high society including gender politics, the commodification of young girls, patriarchal hypocrisy, and the price of privilege that only women incur.

If this sounds familiar, you might be living in the United States in the year 2025. As of this writing, the president is doing everything he can to prevent the release of a list of rich pedophiles, even though he’s “definitely not on it”. In fact, there isn’t even a list. Let’s focus on important things like the recipe for Coca-Cola! Twenty-eight years later, the only thing that’s really changed is the soundtrack. Systematic patriarchal exploitation is as American as apple pie.

As you might have guessed, Eliza Flug’s semi-autobiographical tale leans dark. But it’s not a suffocating darkness. That’s a tonal balance that Megan Griffiths has always deftly straddled in her myriad films about American womanhood (Eden, The Off Hours, Lucky Them, Sadie). Together, this dream team has crafted a weighty story about the ripples created when powerful men use their sovereignty to hurt women, without reproach, time and time again. Griffiths and Flug effectively inform the audience of the dirty deeds without miring us in the acts themselves. We don’t need to see the assaults, because it reverberates through the narrative: folded arms, hunched shoulders, a new bruise, a condom wrapper stuffed in a drawer, a knowing glance, a mysterious car dropping off a teenage girl in the wee hours, a man calling a seventeen-year-old girl, “an old soul.” It’s a shorthand that is familiar to at least 50% of the population. We know what all these things mean because we have all witnessed it or experienced it firsthand.

The film opens with a voiceover, setting the scene and core relationships, which returns throughout the narrative. The tone resembles a diary, akin to Veronica Sawyer narrating Heathers. It is not hard to botch the deployment of a voiceover, which is why Year of the Fox should be taught in film school as a perfect example of how to do it right. A teenage girl wouldn’t be too expository in her own diary. But she would work through her feelings, and record observations she couldn’t say aloud, for fear of retribution.

Another teenager who wrote a similarly-themed diary, is Laura Palmer from Twin Peaks. And that’s not the only parallel Year of the Fox shares with that iconic Pacific Northwest drama. Ivy isn’t Laura Palmer, but she could be Donna Hayward, Laura’s best friend, who Laura attempts to shield from the darkness in her life. Or perhaps even Audrey Horne (Sherilyn Fenn). Much like Ben Horne (Richard Beymer), Ivy’s dad is a powerful and respected figure in the community who uses that position to exploit young women. The Aspen party where the scales ultimately fall from Ivy’s eyes, may as well be One-Eyed Jack’s; the Canadian brothel just over the border from Twin Peaks, where no one checked a girl’s ID before putting them to work.

Year of the Fox was also partly shot in North Bend, where David Lynch filmed the Twin Peaks pilot and Twin Peaks: the Return. Not to the mention the presence of Jane Adams as Ivy’s mother, Paulene; and Balthazar Getty as the titular wily predator who sets his sights on Ivy.

Ivy’s best friend since childhood, Layla (Lexi Simonsen), is a troubled blonde with secrets, a very unstable home life, and good reasons for doing bad things. We learn in the first two minutes of the movie, that Ivy’s parents are divorcing because her dad cheated with Layla’s mom, who has since abandoned her daughter. Still, Ivy compares herself to Layla, who has a more socially acceptable body type and confidence around men. This dynamic, in part, sets Ivy up as the perfect bait for the Fox (Getty). “Lots of men look at Layla,” she confides in voiceover. “But he looked at me.”

Both parents smoke joints like they’re Marlboros and trade barbs through Ivy. The bitterness hangs thick between them. Ivy’s dad, Huxley (Jake Weber, Dawn of the Dead, 2004), is keeping his multiple Aspen properties and the social circle, while Paulene gets a consolation mansion in Seattle. The plan is for Ivy to spend her senior year of high school there, visiting her dad in Aspen on school breaks, before heading off to art school and leaving Paulene to her empty nest. Ivy understands her mom’s pain but wants to stay in Aspen. Paulene needs to get away from Huxley, and she knows too much about her ex to leave Ivy behind. “Your dad has a switch,” she says diplomatically. “He can turn it on and off.” It sounds like bitterness from a jilted woman, but it’s not long before we see just how right she is. Huxley demands that the vibes always stay chill and positive, but he also loves to teach harsh “lessons” in a feigned attempt to ready Ivy for the “real world”. There is so much self-serving calculation layered into his lectures on privilege.

Throughout the film, the narrative reveals the conditions that came with Ivy’s pampered life. Huxley’s parenting style is little more than writing checks, dispensing bon mots and reminding her that she’s lucky to be his daughter. Huxley shames Ivy about her maturity time and time again, as if he has done anything to prepare her for life outside of his sheltered wing. His “no pouting allowed” rule applies, even when his decrees and decisions are life-changing for Ivy. Meanwhile, he’s not accountable for anything he does, no matter who it affects. He reminds her that she’s adopted, as if she could ever forget such a thing. His attitude toward Ivy is one of ownership, investment, and apprenticeship, but never personhood. Never equality.

The whole reason Ivy finds herself at a party full of predators is because Huxley employs her as a designated driver, so he can get as blitzed as he likes, and forgets about her as soon as he walks in the door. “It’s pretty dope you get to live that life,” says a teenage boy who only knows Huxley from his “famous parties” where he indentures underage kids to bartend, and so much worse.

Kudos to the casting director, Amey René, who knocked it out of the park. The main actors deliver in spades, but they’re ably backed by a solid supporting cast. Alma Delfina plays Xiomi, the family housekeeper who essentially raised Ivy but has no parental rights. Arden Myrin is Sibi, Huxley’s trophy girlfriend who has complex reasons for turning a blind eye. There’s also delightful appearance by the Tom Bombadil of indie films, Linas Phillips, as an honest delivery man who blows Ivy’s mind with one line: “Billionaires. They even get their kids to work. Cheapskates.”

A particularly staggering scene sees Paulene recounting a sexual assault from a time before she met Ivy’s father. In a just world, Jane Adams would be nominated for an Oscar for this monologue. The way she tells the story is so matter of fact. “I had a shower, and I had some sleep and I got to work on time.” She even laughs at the end: The weary laugh of a woman who is tired of crying and because the circumstances that allowed this to happen are just so absurd.

On my second watch of this film, it struck me that for all the characters who owe apologies, the only person who really gives one is Paulene. It’s up to Paulene to tell Ivy that she’s not to blame. The actual predators will never apologize because they aren’t sorry they did it. And because there are no consequences for them, they’re not even sorry they got caught.

At this point, you may be questioning the aforementioned tonal balance. But I promise, we do get to see a lot of joy. Ivy draws beautiful pictures. She goes fishing with her dad and has a pretty good time. She hikes with her mother and sees a real fox. The backdrops of Seattle, North Bend, and Aspen are absolutely breathtaking. There is also joy in the music, with a good mix of 70s, 80s, and 90s tunes pulled from the real-life soundtrack of Flug’s teenage years. An unobtrusive score by St. Kilda fills in the blanks.

In her diary-esque voiceover, Ivy says, “it’s hard to trust the good memories through the bad but they were just as real.” That’s life. We endure the ugliness to discover the beauty.

– Jessica Baxter (@TheBaxter)