A Conversation with Kathleen Chalfant & Sarah Friedland (FAMILIAR TOUCH)

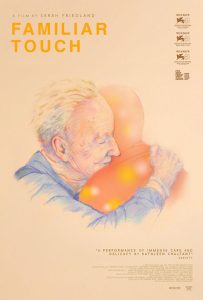

Familiar Touch represents a unique entry in cinema’s exploration of aging and dementia, offering a perspective rarely seen on screen: that of the person living with the condition rather than the family members watching from the sidelines. Director Sarah Friedland’s debut feature, which took home three major awards at the Venice Film Festival 2024 including Best First Film, Best Director, and Best Actress, follows Ruth Goldman as she transitions into assisted living while navigating dementia. What makes this film extraordinary is not just its unflinching yet tender approach to dementia, but its revolutionary collaboration with the residents and care workers of Villa Gardens retirement community in Los Angeles, where the film was shot.

At the heart of the film is Kathleen Chalfant’s luminous performance as Ruth, a role that feels both deeply personal and universally resonant. Chalfant, the celebrated stage actress known for her work in Angels in America and Wit, brings decades of theatrical experience to bear on a character who refuses to be defined by her diagnosis. Working alongside Friedland, a filmmaker whose background as both a choreographer and former caregiver to artists with dementia infuses every frame with authenticity. Chalfant creates a Ruth who is neither victim nor inspiration, but simply a woman insisting on her own agency even as the world around her shifts. Their collaboration represents a rare meeting of artistic vision and lived experience, resulting in a film that treats its subject with the complexity and dignity so often missing from Hollywood’s portrayal of aging.

Hammer to Nail: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. I thought the movie was so beautiful. Kathleen, how did you find your way into Ruth’s specific physicality? And Sarah, were you specific in guiding her to find that physicality?

Kathleen Chalfant: I think maybe Ruth’s physicality is a lot like my physicality. Where Ruth is in space and the circumstances you find her in, the pool, walking, the wonderful magical night dance, all of those things were described in the screenplay because the screenplay and the shot list were very meticulously prepared so that I could just walk into it in some way..

Sarah Friedland: Ruth and how she’s relating to these different spaces, her home of many decades, her new home of which we don’t know how many years, the spaces that she enters into when she leaves the care community for an evening, how she circumnavigates those spaces and moves through them. That was precisely written. I tend to think about screenwriting as a sort of choreographic notation. But then there’s great joy for me in just trusting Kathy completely. When she entered the set, I said, “It’s yours now.” Then I got to watch the particularity of Ruth’s body come through her choices, just her way of moving in the world.

In terms of adjustments or guidance, I would say we only got that specific in very close-up shots of Ruth’s hands, for example. I think it was really just in those close-ups of her hands that we would get as granular as saying, “Okay, let’s release the tension in your palm or extend a finger.” But otherwise, it was more a process of releasing Ruth’s body to Kathy’s.

KC: I played the Rabbi in Angels in America on Broadway for years, and he was an 85-year-old man and I was a late 40s, early 50s woman. So that was harder. Then I had to really seriously think about the movement, but here I was an 80-year-old woman playing an 80-year-old woman.

HTN: It was a great performance. Sarah, you described the early script as reading like a movement score. Can you elaborate on how the screenwriting process worked? And Kathleen, what was your initial reaction to the script?

SF: I’m coming from a background making dance films, and they’ve all been scripted to different degrees, since a lot of them have been made both with professional dancers and non-professional performers, looking at patterns of social choreography of everyday movement and their politics. I often work with what I would describe as found movement. I only think about screenwriting as a form of writing movement, both the movement of bodies and of images and the integration of those two.

Filmmaker Sarah Friedland

The first draft, I say, “it was a movement score,” in the sense that it was really trying to imagine how Ruth was moving and interacting in her home of many decades for the last time and her home of we don’t know how many years for the first time. That said, I wrote it out in screenplay format. But the first draft, this was the first screenplay that I’ve ever written. So it was also a process of learning how to be a screenwriter. I start with movement with everything I do. That’s just how my brain works.

It was a process of putting Ruth’s movements into that form. Over many years, since I wrote the first draft of this when I was still a college student, I kept picking away at it while I was working for other filmmakers and while I was working as a caregiver. It was just a process of finding little details that I learned from different experiences I had largely with older adults that I was working with over these years. It was a process of accumulation of finding more of the character arcs and the dialogue. You start with movement and then the rest follows.

KC: By the time I saw the script, it read like a conventional script. I start with the words. So we met in the middle.

HTN: Kathleen, you said you wanted to do this as a tribute to your friend Sybil who has dementia. And Sarah, this came from your grandmother’s experiences and also being a caretaker. How did those personal connections shape what you brought to Ruth?

KC: I discovered how much Sybil informed what I was doing the first time I saw the movie. It wasn’t clear to me that I was going to be able to watch the movie. I work mostly in the theater, one of the joys of the theater is you don’t have to watch yourself. So I thought, “Oh, this is going to be a rough 90 minutes here watching this thing.” And almost from the beginning, I saw how much Sybil had informed my performance much more than I had any idea of consciously. So I could watch the movie. That was also an entirely unexpected thing.

SF: I think the first thing that I learned from my experience with my grandmother is I longed to see how both my family and the world around her perceived her when she had dementia. They perceived her as a person who was not fully there. It was in that moment of loving her and seeing that loss that I started longing for an idea of selfhood that wasn’t just cognitive and thinking about the parts of ourselves that are expressed through our senses, through our bodies, that we are not just the “I think, therefore I am” version of ourselves, that our humanity is more than our cognition. I think that was one of the biggest things that I took from that experience.

Then my experience as a care worker. So many people would say, “As a young person going to work with all of these old people, isn’t it depressing? You must be depressed all the time doing this work.” And it was the opposite. It was one of the most joyful, life-affirming experiences I’ve ever had. I noticed in that job that it was largely the people around the person with dementia that were perceiving this story as a tragedy and that the person themselves didn’t see their daily life as a tragedy. Not that it didn’t have pain, struggle, loss, we all have that at any stage of life, but that the continuity of who they were was stronger than that loss. Noticing the joy and absurdity and poetry of everyday life in that caregiving relationship really informed the tone of the script.

HTN: Besides the first 15 minutes where we have that twist that Steve is Ruth’s son, you avoid psychological trickery of films like The Father or more recently A Great Absence. Kathleen, you also play this character differently than I’ve seen the disease portrayed in the media. Was this a conscious rejection?

KC: I did what my job was, which was to play the character that was written in the script. But the character seemed right to me, given my experience up to that time with Sybil, who at the time that we shot the movie, which was two years ago, was in just about the same place that Ruth was. The truth is that we live life in the moment. From the inside, people don’t experience life as a continuing tragedy. You experience what happens to you. In the middle of this movie, the moment when Ruth feels rejected and humiliated as a lover is a tragic moment for her and truly tragic. That is much harder for her than the fact of living every day and growing older. I think, as Sarah said, most films that we see about dementia are seen from the point of view of loved ones and family. From the point of view of loved ones and family, it often looks like continuing tragedy. From the inside, from the person who’s living their lives, it’s just living your life, one thing after another.

HTN: The Borscht recipe moment is so great. I love how you keep the camera in that one medium shot as she delivers the whole speech. This leads to a small but extremely powerful moment as she fights back those tears. For me, the tears meant that she would be letting go. Talk about that sequence and what was important to each of you.

HTN: The Borscht recipe moment is so great. I love how you keep the camera in that one medium shot as she delivers the whole speech. This leads to a small but extremely powerful moment as she fights back those tears. For me, the tears meant that she would be letting go. Talk about that sequence and what was important to each of you.

SF: We should say that the Borscht recipe comes from Molly Katzen, the great cook and cookbook author of the “Moosewood Cookbook,” who was a creative advisor on the film and designed the recipes and meals that Ruth makes, as well as Ruth’s archive. Ruth’s history as a cook and her taste memories were largely lent to us by Molly. I grew up eating that recipe. So that Borscht recipe is very particular.

We talked about Ruth sort of being all ages and no ages, which is to borrow a quote from the great academic Lynn Segal, who writes about age identity and aging. Throughout, I think one of the great joys of this film was getting to play with that age identity together. In that scene, Kathy has said before that Ruth is in the present moment. She is Ruth at 80, Ruth in the current moment as opposed to a younger self. I think there’s almost the desire to negotiate with her caregiver as if recognizing that the presence of this nurse practitioner across from her and her sitting in a care facility says something about a reality that she is still negotiating how much she wants to accept or deny. She calls upon her own skill set as the tool she has to almost barter with reality.

KC: It is one of the few scenes in which we see Ruth grappling in the moment with loss. But in this case, it’s a battle. She’s fighting to say, “Look, if I can do this, then what you think isn’t true.” I’m not sure that she believes that she’s won that battle, but it’s a battle. The only moment it seems to me when it feels as though Ruth is entirely conscious of her loss is when she remembers that Steve is her son in the shower and knows that she probably won’t remember that in a minute and mourns that loss.

HTN: H. Jon Benjamin is so incredible in this movie, and the dance sequence towards the end is one of my favorites of the year. Talk about how that moment came to be and working with Jon.

SF: We both love Jon. He’s the best. We were incredibly lucky in that the supporting actors working with Kathy, not just Jon, but also Carolyn \ and Andy McQueen were just extraordinary collaborators.

We worked with a wonderful casting director named Betsy Fippinger, and we had been thinking about different people for this role. We had this list of really talented actors who were right for the role on paper, but we just knew, even though they were all talented, everyone we had thought of was not right for Steve. Our producer, Alexandra Byer, is a huge Bob’s Burgers fan, and said it. Betsy and I were both like, “Oh my God, yes, that’s perfect.”

I met with Jon and we immediately hit it off on a personal level. Similar to my first conversation with Kathy, we ended up not really talking about the movie and just talking about other shared points of contact in life. One of the things I remember talking about with him in that first meeting was the discomfort of his relationship to Ruth’s sexuality, of her coming on to him and talking about his background as a comedian. He said that comedians, much of their job is courting discomfort. In that way, this made total sense to work on this scene together.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this film as a coming-of-age film and what kind of tropes and architectures from that genre could we borrow. I thought about that scene when he comes to visit almost as the prom scene at the end of the coming-of-age film, but a prom scene in which the female character thinks that her date is perhaps the prom king and that in that moment for Jon or for Steve, he has to accept that he is whoever she thinks he is as opposed to asserting his identity as her son.

KC: It was wonderful to dance with him. It wasn’t choreographed. We just played the song and then we danced. He’s a wonderful partner, Jon. Always present. He is such a good and gentle man. It was endless joy, all the scenes we had together. The uncomfortable ones and then the wonder of the prom king.

– Jack Schenker (@YUNGOCUPOTIS)