BERLINALE ‘10 WRAP-UP – Part One

As overwhelming as the 60th Berlinale Film Festival is to experience, it’s even more overwhelming to write about it, particularly since I was there over the course of most of the fest. The event itself has so many aspects—from the gargantuan program of films, including a Retrospective strand curated by critic David Thomson to celebrate 60 years of the Berlinale this year, to the European Film Market, Co-Production Market and World Cinema Fund, to the Talent Campus—it can be dizzying and disorienting when one first glimpses the massive crowds, the klieg lights, and the red carpets, representations of the antithesis of all I hold dear in a festival experience.

But the Berlinale is a far more intimate festival than it first appears, and once you get your bearings (no pun intended) and dive in, it’s fairly easy to navigate. Being a New Yorker, I found the diversity, the worlds upon worlds you encounter around every corner as the festival wends its way into every nook and cranny of the lovely city of Berlin, invigorating. Since I was also a first-time visitor to the city itself, the festival enabled me to get around and to “focus my gaze” a bit, as Festival Director, Dieter Kosslick, suggests one do in his introduction to the 464-page behemoth of a catalog. The city, somehow, contextualized my festival experience, making it more human-scale than I first thought it would be.

But the Berlinale is a far more intimate festival than it first appears, and once you get your bearings (no pun intended) and dive in, it’s fairly easy to navigate. Being a New Yorker, I found the diversity, the worlds upon worlds you encounter around every corner as the festival wends its way into every nook and cranny of the lovely city of Berlin, invigorating. Since I was also a first-time visitor to the city itself, the festival enabled me to get around and to “focus my gaze” a bit, as Festival Director, Dieter Kosslick, suggests one do in his introduction to the 464-page behemoth of a catalog. The city, somehow, contextualized my festival experience, making it more human-scale than I first thought it would be.

As for that unwieldy program, Kosslick has garnered much negative press, for this year’s offerings in particular, specifically the Wettbewerb, or Competition selections, of which I saw only three. By the time I figured out how the system worked, most screenings for these films were sold out. To be honest, schlepping to a theater and standing around for an hour in the hopes that I might get a seat if I was lucky (at the suggestion of the press office) is just not my thing; I’m just not going to do it—not as an accredited journalist covering the festival, at any rate. My naiveté and inexperience saved the day, as it usually does, since I didn’t get too caught up in “must-sees,” but relied on my instincts and interests (and what my schedule would allow) and went to see the “smaller” fare. With a couple of exceptions, I found the docs to be much stronger, as a rule, than the narrative selections, but saw a very strong strand of narrative short films and a couple of real feature-length gems.

I arrived the day after the festival started on the 11th and departed the day before the festival wrapped up, so I had the time to spread my wings a bit and investigate what was going on in each zone, each strand, dabbling here and there since my advancing age seems to be accompanied by a strenuous case of adult-onset ADD. Every screening and event I attended had robust crowds, most of the screenings sold-out entirely. Long, long queues of very patient people waiting to buy tickets every day was just part of the scenery. And like most festivals, the parties were really where the action was, a grand chance to meet fellow cinephiles, as well as a dazzling array of talented and dedicated programmers and curators from all over the world.

I arrived the day after the festival started on the 11th and departed the day before the festival wrapped up, so I had the time to spread my wings a bit and investigate what was going on in each zone, each strand, dabbling here and there since my advancing age seems to be accompanied by a strenuous case of adult-onset ADD. Every screening and event I attended had robust crowds, most of the screenings sold-out entirely. Long, long queues of very patient people waiting to buy tickets every day was just part of the scenery. And like most festivals, the parties were really where the action was, a grand chance to meet fellow cinephiles, as well as a dazzling array of talented and dedicated programmers and curators from all over the world.

Even the market had a very intense social aspect to it. Every day I would enter and go visiting, stepping up to various desks to see what they were selling and interested in buying. It was a great education for a neophyte Berlinale spectator and participant, and budding international producer.

Getting back to the films: I think any ambitious arts event like the Berlinale prides itself on exhibiting works that push discussion, welcoming dissent and outrage, allowing a spectator to discover her “discomfort” zone in terms of what she can bear to watch, or choose to give an inordinate amount of patience to. Sometimes sitting through that discomfort paid off; other times it, distinctly, did not. And I did walk out of a couple of films, a regular sight at every screening I attended, which is a strong statement when one’s waited on line for two hours to buy a ticket. There were many bizarre, unsettling, and challenging pieces of work. Lots of the German films were just plain weird; sometimes, I felt like someone had slipped something into my drink when I wasn’t looking since I would helplessly fall into a deep slumber from sheer disorientation.

At any rate, in the next couple of posts, I will talk about some highlights and experiences—films, Talent Campus projects, seminars and gatherings. All in all, it was an exhilarating time, one I hope to experience again in the years to come. What follows is a rundown of the twenty-three films I saw during the course of the week. While that’s probably a very, very low amount compared to, say, a (cranky) Hollywood Reporter critic who sits through six or seven films a day until his brain drips out of his ears, I wanted to experience the festival in its entirety. And, honestly, I wanted to party in Berlin as much as I could. Party, film? Party, film? Party, film? Party, party, party.

I will note when more extensive reviews of some of the films, mentioned by section, will be forthcoming and/or requested by my gracious and generous editor (or they’ll be posted on Still in Motion). Timing will be delayed, in some cases, in order to coalesce with a domestic festival début, or just to wrap my mind around what I want to say about more complex, emotionally resonant work. I’m slow that way.

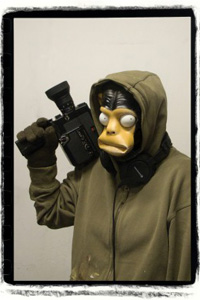

Exit Through the Gift Shop (directed by Banksy) — This first feature is “about a man who tried to make a film about me,” says its director, the renowned Bristol, UK graffiti artist, a person who has fiercely guarded his identity to avoid arrest and jail time for his painterly transgressions. He now exhibits at places like the MoMA and London’s Tate Modern. French shop owner Thierry Guetta stalks Banksy with his camera, as well as other “vandals” of the streets. And then Banksy turns the camera right back on Guetta. What ensues is a disastrous mess of a film, frustrating and maddening to watch due to the bumbling, stumbling way both filmmaker and subject (and who’s to say, really, which is which) encounter one another through their lenses. It’s kind of an ingenious little crime caper, ultimately, on the quantification of both the artist and the “art” he makes, and the bizarre symbiotic (in this case, succubistic) relationship that develops between documenter and documentee. I had a good time.

Exit Through the Gift Shop (directed by Banksy) — This first feature is “about a man who tried to make a film about me,” says its director, the renowned Bristol, UK graffiti artist, a person who has fiercely guarded his identity to avoid arrest and jail time for his painterly transgressions. He now exhibits at places like the MoMA and London’s Tate Modern. French shop owner Thierry Guetta stalks Banksy with his camera, as well as other “vandals” of the streets. And then Banksy turns the camera right back on Guetta. What ensues is a disastrous mess of a film, frustrating and maddening to watch due to the bumbling, stumbling way both filmmaker and subject (and who’s to say, really, which is which) encounter one another through their lenses. It’s kind of an ingenious little crime caper, ultimately, on the quantification of both the artist and the “art” he makes, and the bizarre symbiotic (in this case, succubistic) relationship that develops between documenter and documentee. I had a good time.

Mammuth (directed by Benoit Delépine and Gustave Kervern) — French icon, Gérard Depardieu, plays the porky main character, a 60-year-old slaughterhouse worker that is about to retire when he discovers that half a dozen of his employers never registered his earnings. In order to receive his full pension, the onus is on him to provide the proof of his employment over the past six decades of his life. This starts one of those dreadful “journeys of self-discovery” as he and his wife mount his Mammoth motorbike (he is also called Mammuth) to traverse the places of his past. As Depardieu’s malleable face and soulful eyes are always wonders to behold, I stayed with it, but it does devolve into sheer dopiness most of the time and I lost patience after a while. Not too harmful, but it lacked the substance I was hoping might be there.

Der Räuber (directed by Benjamin Heisenberg, who is also the co-founding editor of the film magazine Revolver) — Shot in CinemaScope with a very sparse script by Wolfgang Widerhofer, this story is about a man who is a successful marathon runner and also robs banks. His obsession with physical prowess and muscle power forces him to partake in these criminal acts (and escapes) several times a day—all of it in service to an apparently severe dopamine addiction and the joy of the stamina in running as fast as he can for as long as he can—to nowhere. This second feature of Heisenberg’s is based on a novel by Martin Prinz, which, in turn, is based on a real-life story of an Austrian man. The first thirty to forty-five minutes are thrilling in their intensity, providing a sheer adrenaline rush as we run beside this human blur for what seems like hours. It’s stylish, to be sure, but lacks the substance to sustain its 96-minute “running” time, becoming tedious and repetitive and never really allowing us to discern much of what might motivate him to do what he does. Maybe we’re not supposed to care? Unclear. Like most of the films I saw, this one, too, was heavy on style and form, very light on substance and story, thus making it, ultimately, a bore, aka, much ado about nada.

Der Räuber (directed by Benjamin Heisenberg, who is also the co-founding editor of the film magazine Revolver) — Shot in CinemaScope with a very sparse script by Wolfgang Widerhofer, this story is about a man who is a successful marathon runner and also robs banks. His obsession with physical prowess and muscle power forces him to partake in these criminal acts (and escapes) several times a day—all of it in service to an apparently severe dopamine addiction and the joy of the stamina in running as fast as he can for as long as he can—to nowhere. This second feature of Heisenberg’s is based on a novel by Martin Prinz, which, in turn, is based on a real-life story of an Austrian man. The first thirty to forty-five minutes are thrilling in their intensity, providing a sheer adrenaline rush as we run beside this human blur for what seems like hours. It’s stylish, to be sure, but lacks the substance to sustain its 96-minute “running” time, becoming tedious and repetitive and never really allowing us to discern much of what might motivate him to do what he does. Maybe we’re not supposed to care? Unclear. Like most of the films I saw, this one, too, was heavy on style and form, very light on substance and story, thus making it, ultimately, a bore, aka, much ado about nada.

I only managed to see a single shorts program (one of six), but it was a really strong one. I am not a fan of shorts programs, in general, truth be told. I find them enervating and I lose focus after a while, so that by the fourth or fifth selection, I don’t want to shift gears anymore into yet another universe. I would much rather see one short programmed in front of a feature and I was told that this used to be the way they were exhibited, for the most part. I know it’s much easier to schedule blocks of short films together in 90-minute or two-hour time slots, but I think the former way of showcasing these works would give them much greater heft and power, qualities each of these selections (with one exception) had in abundance in different ways. As it was, this was yet another non-contextualized collection. If there was something thematic going on, it was lost on me.

In order of appearance:

Glukhota (Deafness) (directed by Myroslav Slaboshpytskly [no typos here], 11 minutes) — This Russian selection packed a wallop. Beautifully shot, this is a short episode in the lives of some students at a deaf-mute boarding school, reconstructed in real time. There is profound character development in camera and behind the lens, and Slaboshpytskly conveys a brooding and intense mood throughout. The film is totally silent except for very muted ambient noise and human sounds muffled behind glass. Creepy and deeply disturbing, this short story writer has found his art form, as well, in cinema. This is his second film at Berlinale, following Diagnoz in 2009.

Händelse Vid Bank (Incident by a Bank) (directed by Ruben Östlund, 12 minutes) — This Swedish selection won the Golden Bear for Best Short at this year’s festival. It’s a forensic (and very funny) reconstruction of a bank robbery gone terribly wrong, witnessed and recorded by bystanders in 2006 in Gothenburg, Sweden. There were 96 people carefully choreographed for the camera in this sharply written and realized film, which also contains delightful displays of slapstick humor in abundance. Very much a crowd pleaser.

Photos of God (directed by Paul Wright, 28 minutes) — This selection from the UK was my least favorite of the bunch, an indulgently long short. Shot in an impressionistic and painterly style, I found the story utterly derivative and predictable, the acting, for the most part, overwrought. It’s about a young man (a highly watchable actor named Farren Morgan) who must look after his mother. Along with her, he is suffering from an unrelenting isolation without any resources to break out of the oppressive life force that surrounds him in the guise of this woman who is completely dependent on him. They are both victims of haunting memories of a family tragedy—a car accident caused by a drunk father, disabling the mother and killing the baby sister. Unrelentingly grim, and starting with its title, inexcusably pretentious.

Ich Muss Mich Künstlerisch Gesehen Regenerieren (I Need To Rejuvenate Myself Artistically) (directed by Christine Grosse and Ute Schall, 19 minutes) — This German film is a hoot and had the audience in stitches. Charlotte, a director, makes a feature film in which she succeeds in successfully illustrating the resonance of one person’s private thoughts into political action. She then promptly falls into a depression. In order to “rejuvenate herself artistically,” she decides to make a documentary, a social issue documentary about poverty and social hardship, a completely contrived piece. She directs her “subject” with an iron fist as her bumbling film crew tries to capture the “reality” that’s transpiring in front of the camera. The performance by Grosse in front of this “documentary” lens is absolutely hilarious, as is that of every member of the absurd crew, all of whom, literally, fall over one another to capture every eye twitch, every drop of condensation on a coffee spoon.

12 Jahre (12 Years) (directed by Daniel Nocke, 4 minutes) — A fantastical-looking tale, this super short animated piece tells the story of a tortured soul, a “big dog” that after twelve years has grown embittered by the hostility of everyone around her towards her relationship. And she’s had it. Delightful.

In Part Zwei, I will share some (not all) of the selections I saw from Berlinale Special, Panorama Special, Panorama and Panorama Documentaries, plus a couple of other American films that shone like one of the bright stars in the dazzling trailer that celebrated sixty years of Berlinale. Don’t ask me why, but I welled up every time that thing played.

And, in Part Drei, Berlinale Talent Campus DocStation presentations, and “Fear Eats the Soul,” (the title of a Fassbinder film, how precious) a panel discussion / supposed debate about the state of modern film criticism with Berlinale Retrospective curator David Thomson, Sight & Sound editor Nick James, and Salon.com’s Stephanie Zacharek, moderated by Dana Linssen, editor of Denmark’s de Filmkrant. Interesting, but a huge disconnect between these people and their young audience. More on this in a bit.

And, last but not least, my last evening in Berlin spent at the elegant and campy Teddy Awards!, seated third row center with my fellow hooker, Mr. Crayton Robey, director of Making the Boys (Panorama Documentary section). A gay time was had by all.

— Pamela Cohn

ALSO:

***BERLINALE ‘10 WRAP-UP PART TWO***

***BERLINALE ‘10 WRAP-UP PART THREE***

***BERLINALE ‘10 WRAP-UP PART FOUR***