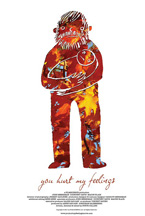

(You Hurt My Feelings world premieres at the 2011 Los Angeles Film Festival. It screens on June 17, 21, 22. Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

A male nanny—a gentle, meaty, confused presence—is forever trying, and failing, to get control of a working mom’s two little girls, and, we sense, of his life in general. He lacks any adult self-confidence or sense of authority. In the opening shot of You Hurt My Feelings, and repeatedly through the film, John (John Merriman) is seen laying on the floor, his intense, worried eyes staring into space. He exists in a state of guilt and inadequacy, particularly in relation to his frozen-in-resentment girlfriend Courtney (Courtney Davis).

Writer-director Steve Collins creates a visual shorthand for the recurring, titular state of hurt feelings: a frontal traveling shot of a character (usually Courtney) striding forward along the side of the road, as the offending person trails behind her at a distance. Courtney’s anger remains unexplained, and as You Hurt My Feelings progresses it becomes evident that Collins has built his film around a series of highly dramatic plot points, each of which has been excised from the story—leaving only their emotional fallout. The result is a stylized film cloaked in a naturalistic visual style. And it absolutely works, thanks in large part to the richness of the script and outstanding performances.

A new man, Macon (Macon Blair), appears in Courtney’s life, and he’s John’s polar opposite: playful, outspoken, ridiculous, and effortlessly charming, even coaxing a half-smile from her stony face. He quickly develops a huge guy-crush on John. After helping him jump-start his stalled car (another recurring theme), Macon gets his beer on and gushes, “It’s just nice to have a buddy, a good buddy, a really, a really good buddy—it’s great!” Blair is an exciting actor to watch—he does some fantastic physical comedy on his front lawn, drunkenly playing with John’s attempts to be responsible and get him safely inside the house. Later, he conveys volumes of subtext and terrified humanity in a single wordless close-up.

Gradually the story starts—unsettlingly—to jerk forward at key moments. We miss crucial scenes and dialogue; Collins proposes that common knowledge about story can be turned inside out, that plot points can be left to the viewer’s imagination by showing their aftermath. He focuses on the shifting texture of his characters’ lives, their loneliness, their isolation from each other, as the love triangle that started with John and Macon competing for Courtney increasingly leaves her the odd woman out.

Gradually the story starts—unsettlingly—to jerk forward at key moments. We miss crucial scenes and dialogue; Collins proposes that common knowledge about story can be turned inside out, that plot points can be left to the viewer’s imagination by showing their aftermath. He focuses on the shifting texture of his characters’ lives, their loneliness, their isolation from each other, as the love triangle that started with John and Macon competing for Courtney increasingly leaves her the odd woman out.

Credit must be given to cinematographer Jeremy Saulnier’s bold and imaginative use of an austere box of toys. He creates a theatrical sense of space by shooting a John-chasing-down-the-little-girls scene through a loose thicket of bare branches. He accentuates the working-mom’s whiny rant by placing her small in the background as her unconcerned infant plays with a doll in close-up. A lovely underwater shot paints the simple joy at the heart of John and Macon’s friendship.

Collins’ film is painfully relatable for anyone who’s paddled around in the shallow end of the economy. Brief interludes of simple happiness—a day at the beach, a furtive swim in someone else’s backyard pool, John’s kind and nurturing connection with the little girls—can’t disguise the downward spiral of John’s life. He faces a series of tragic-comic humiliations; the droning, pseudo-caring monologue with which the working mom, who’s been offered childcare at her work, fires him (“I have to take this benefit” is her mantra) is torn from today’s headlines and laser-accurate. And if that doesn’t make you squirm, wait ‘til his retirement-age parents take him to the mall to buy him a suit.

Merriman’s performance is a gem, his big-and-strong physicality contrasting with and accentuating the daydreaming, boyish sweetness and passivity of his character. Blair’s drunken words about having a buddy are a beacon in the dark night of John’s existence, and increasingly come across as the film’s cri de coeur.

You Hurt My Feelings is like a Buster Keaton comedy of pain slowed all the way down to the depressive pace of jobless-recovery culture. It’s poetic and subtle, never more so than in its oblique final scene, which could be interpreted as either hopeful or the death of hope. It rarely raises its voice, but look inside and you’ll find a funny and heartfelt microcosm of the malaise (and moments of joy) of American life in the here and now.

—Paul Sbrizzi

Mmackay

Beautiful and astute review Paul!