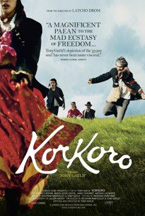

(Korkoro is being distributed by Lorber Films and is now available on DVD. It opened in New York on March 25, 2011 and will be arriving elsewhere over the coming months. See here for a full list of dates.)

Korkoro‘s story is one that’s gone largely untold. The plight of the Romani people (read: Gypsies) during World War II tends to be relegated to a footnote at the end of the long list of atrocities that comprised that conflict. This is both unsurprising and symptomatic of their status as one of the most openly maligned group of people on earth. In spite of this, director Tony Gatlif’s film is neither a pity party nor an emotionally manipulative attempt to drum up sympathy for its marginalized subjects. Instead, it’s a decidedly straightforward march into dark territory nonetheless suffused with the spirited demeanor of its characters. There already exist plenty of stories about unbreakable spirits set against wholly dispiriting backdrops (including and especially World War II), but this doesn’t quite feel like any of them. If Korkoro isn’t quite a tale of uplift in the same vein as, say, Life is Beautiful, it’s because Gatlif’s characters don’t aim to transcend their circumstances so much as exist outside of them.

The title itself translates to freedom in the Romani language, but there’s little of it to be found here. The Romani are a nomadic people who remain untethered to any one place, but this lifestyle is throttled early in the film by a law banning their wandering ways for the duration of the war they’d hoped to avoid. Wanderlust notwithstanding, Korkoro thus takes place largely in a quiet French village in which these characters—who have something of a leader in a charismatic oddball named Latouche—have already spent time. “The gypsies are back! The gypsies are back” shouts a child upon their return, and she isn’t the only one to notice: chickens flee to their coop; dogs bark. Through such subtle and not-so-subtle nods, it’s clear that the barely-tolerated bunch are seen as nuisances at best, pariahs at worst. And, though they remain the same the people they were when last they visited, Latouche and his gang quickly come to find that the village has changed. What was once an icy coexistence has turned blatantly hostile. Eventually branded vermin by a man they once trusted, the Romani have exactly two people willing (at their own peril) to come to their aid. Gatlif grants this aspect of the tale more attention than the inherent cruelty of of the Romanies’ treatment, and Korkoro is made better by it: the concern is more with how people live through such times rather than the untimely fate being different so often leads to.

For the most part, Gatlif allows the proceedings to unfold on their own without embellishment. His directorial approach is akin to that of a documentarian charting his characters’ actions with an almost anthropological eye. What easily noticeable flourishes he adds tend to be understated: a gentle mist obscuring an abandoned camp; a wired fence swaying in sync with soft piano strokes in the film’s striking opening shot. Rarely overt, often observant, Korkoro offers snippets of meaning that leave much of the interpretive legwork to the audience. This evenhanded approach sometimes verges on emotional distance, but such moments are quelled by the Romanies’ inherent likeability. While the rest of the world sinks into despair, they remain an eccentric and roving band of merrymakers content to simply eke out their own existence with as few forays into—and intrusions from—the outside world as possible. They sing, they dance, and all the while the townsfolk regard them with an ever more suspicious and angry gaze.

For the most part, Gatlif allows the proceedings to unfold on their own without embellishment. His directorial approach is akin to that of a documentarian charting his characters’ actions with an almost anthropological eye. What easily noticeable flourishes he adds tend to be understated: a gentle mist obscuring an abandoned camp; a wired fence swaying in sync with soft piano strokes in the film’s striking opening shot. Rarely overt, often observant, Korkoro offers snippets of meaning that leave much of the interpretive legwork to the audience. This evenhanded approach sometimes verges on emotional distance, but such moments are quelled by the Romanies’ inherent likeability. While the rest of the world sinks into despair, they remain an eccentric and roving band of merrymakers content to simply eke out their own existence with as few forays into—and intrusions from—the outside world as possible. They sing, they dance, and all the while the townsfolk regard them with an ever more suspicious and angry gaze.

Largely indifferent (though hardly hostile) to their human counterparts, the Romani are exceedingly kind to animals—especially their horses, with whom they have an almost superstitious bond. Though the characters’ communal eccentricities are many, they’re grounded by a deep sense of filial strength. Gatlif’s portrayal of these men and women is certainly sympathetic, but at no point does it seem overly so. He isn’t tugging on our heartstrings so much as briefly drawing our attention to an oft-overlooked struggle, and doing so in a humble and effective way. But nomads and strangers make easy scapegoats, and against such odds—the largest war ever fought, an occupied country turning on its unwanted inhabitants with an us-against-them mentality—they’re clearly outmatched.

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail