The First Annual Nitrate Picture Show: A Review

I had an elderly Russian cinematography professor in college who, whenever confronted with a situation in which nothing could be done, would throw up his hands and proclaim us at the mercy of “our friends from Rochester,” as if the birthplace of Eastman Kodak was some kind of godlike entity; the conjuror of fate that all filmmakers were subject to. This is the same level of Mesopotamian mythology that I’ve heard plenty of portentous cinephiles assign the city, talking about it with the queasy rustbelt romanticism reserved for cities ruined by dying industry; a Gothic brick and steel shrine to its own obsolescence.

I had an elderly Russian cinematography professor in college who, whenever confronted with a situation in which nothing could be done, would throw up his hands and proclaim us at the mercy of “our friends from Rochester,” as if the birthplace of Eastman Kodak was some kind of godlike entity; the conjuror of fate that all filmmakers were subject to. This is the same level of Mesopotamian mythology that I’ve heard plenty of portentous cinephiles assign the city, talking about it with the queasy rustbelt romanticism reserved for cities ruined by dying industry; a Gothic brick and steel shrine to its own obsolescence.

I always thought this ruin-porn fetishism of Rochester was pretty goofy and more than a little condescending, but that’s probably because it also happens to be my hometown (alongside Lydia Lunch, Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, and Emma Goldman upon moving to America). I am very happy to report that I did not spend the first seventeen years of my life in an apocalyptic wasteland, and was excited among many other reasons for the George Eastman House’s Nitrate Picture Show, as it would finally serve as a way to get the New York-denizen film critic clique seven hours west via Amtrak to see for themselves that the city remains pretty much a moviegoer’s paradise. And then I stepped off of the Megabus onto Pitkin Street and was immediately greeted by a giant mound of mordant dust blowing wistfully in the spring breeze. A crooked streetlight framed the Skylark Lounge, the location of the Nitrate Picture Show’s nightly afterparties. The Inner Loop, the freeway that ensconced downtown that Rochesterian’s loved to loathe for so long, was being torn to shreds. I had known this, but the fact that the destruction was going to be some of the traveler’s first view of the city was pretty entertaining. Moving past the yawning construction site by a block, it’s immediately obvious how elegant the rest of Rochester’s East End is, abetted by the perfect spring weather (it was probably snowing the week before, but this secret was kept from the out-of-towners).

The idea of an all-nitrate print film festival could be considered a bit precious as is, but to then be viewing these prints inside of a literal museum built affixed to a sprawling, pillared, ivy-smothered mansion built in 1905 in the heart of a preserved historical district in the fertile crescent of film production suggests something so overwhelmingly unrepeatable and insular that it would be hard to separate the absurd privilege of the experience from the actual quality of the prints. It’s the kind of event that effortlessly generates blatant over-exaggeration. Was it actually life-changing, Twitter dweeb, or are you just saying that to establish your cinematic dominance over your jealous, far-flung followers? Is “beauty” just some term that we affix to any antiquated curiosity or are there actual, discernible benefits to this format that nowhere but the George Eastman House is both equipped to play and does so regularly?

By the end of the first of nine screenings (Casablanca) I had my answer. Nitrate prints aren’t scarce just so smarmy nerds can be pleased with themselves if they get the chance to see one. They’re scarce because of decades of human error and neglect, making aging prints that contain the already unstable and highly explosive compound too dangerous to be shown. Nitrate film can’t be stored among canisters of acetate-based “safety” film. Unless it’s kept under precise conditions, it releases an oxidizing agent that would attack the other prints. And so it was easier to let those prints wither and collect dust while the industry switched over to less lethal and easier to project options. The few that remain, (this particular print of Casablanca was the last nitrate print ever projected at the MoMA) are brief glimpses at what was, and what ideally should still be, the preferred, “actual” screening format. As the late film preservationist James Card put it, “the original [nitrate] positives should be looked at as long as they can be put through projectors. Otherwise you’re not talking about films, you’re talking about facsimiles.” Festival director and Eastman curator Paolo Cherchi Usai continually emphasized that this was a festival of “film conservation.” Nitrate isn’t just some curio but another of Hollywood’s dwindling precious, unrenewable resources (alongside drinkable water and breathable air).

Each individual film became an event. I’d seen movies like Casablanca (cruelly) and Leave Her to Heaven (one of my favorites) dozens of times on splotchy DVD transfers, but I had never seen them like this. None of these prints, the majority of which were from the 1940s, showed any signs of discoloration. Colors on nitrate are exactly as they were meant to be seen. Nitrate retains the tactile textures of acetate prints, but with more depth: the fiery beams of hard light that play on the backgrounds during the last act of Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus had actual dimension and stood out like bloody gashes on the frame. Even the slight flaws of the old prints were sort of endearing: when films deteriorate they don’t do so evenly, making “shrunken” prints thinner in some places than others. While there’s enough wiggle room in the perf for the shrunken stretches to safely fit on the sprockets, the film will occasionally lose focus. A projectionist in the audience said that they often have to ride the lens, choosing which part of the frame to focus on in the damaged sections causing a weirdly individualized experience. Historian and critic David Bordwell was sitting next to the projectionist, and upon hearing this exclaimed “the projectionist as auteur!” The fact that this comment elicited an appreciative collective guffaw from the surrounding rows probably tells you quite a bit about the festival’s clientele.

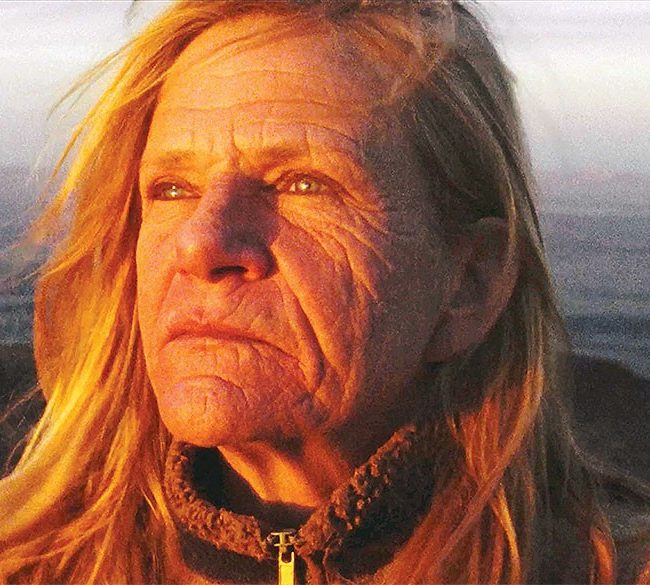

Of all of nitrate’s finer qualities, I was most consistently blown away by the precision of the color. There’s the velvet dress worn by Kathleen Byron at the end of Black Narcissus. How had I never realized just howstriking the burgundy of the fabric was before? How much it compliments her vengeful, bloodshot eyes and stands out in the thick of the fog-laden forest? With every transfer and remaster the Technicolor glory of these films (in addition to those listed above 1949’s Samson and Delilah and 1937’s Nothing Sacred were both in Technicolor and played at the festival) are lost in a sort of “loudness wars” of color; bleaching them of their meaning and impact. Much of this impact was due to the expertise of Natalie Kalmus, the head of Technicolor’s Color Advisory Department and the person with the most screen credits at the festival. Kalmus dictated over the color placement on every single film shot in Technicolor between 1930 and 1950 with an unquestionably stylish fist, writing in her personal papers that her plan for each film should function as a “musical score,” with notes for the corresponding intensity of a color at any given moment. On Black Narcissus she is credited as “colour control,” which, while technically accurate, gives a good indication of how directors viewed her: as a confining nuisance meddling with their art. Still, popular or not, Kalmus’ work has aged well. When the winter scenes of Black Narcissusburn off into the carnal, manic reds and oranges of the climax there were audible gasps in the audience, and the colors in Samson and Delilahwere no less incredible. On nitrate it is inescapably obvious just how masterful Kalmus was, and just how depressing the color in modern films is in comparison: all milky, neutral earth tones meant to conceal the lack of true black in digital projection.

It’s weird talking about nitrate in terms of what it “retains” from acetate prints, as if it were some newfangled, advanced technology just because I was seeing it for the first time. But it’s hard not to see it as an advancement of sorts from HD and DCP, where we have yet to figure out something as simple as how not to make the image smear and lag with every pan of the camera. Nitrate is a timeless artifact; simultaneously anchored to the past while also being a free-floating, unmoored ideal of beauty, like Jennifer Jones in William Dietrle’s Portrait of Jennie. At the end of that film, when Joseph Cotton throws himself headlong into self-destruction, taking a boat into the fury of a hurricane to see the untethered, time-traveling ghost of Jennie one last time before she fades away, something unexpected happened. The curtains on either side of the screen began to pull back and the image expanded. While a massive, green-tinted lightning bolt struck on screen and waters pounded the newly christened widescreen frame, the energy in the room reached a trembling fever pitch. After the movie the ended there was a stunned silence.

“So, uh, that aspect ratio thing,” managed an older viewer, tentatively saying what probably most of us were thinking. “That’s not on the DVD.”

These experiences are rare and fleeting. Our laptop screens can’t give them to us, and DCPs sure as hell can’t either. The first morning of the festival, after a workshop on how to make nitrate film, a British Navy instructional film about proper nitrate safety procedures entitled This Film is Dangerous played (on “safe” acetate 35mm). It basically amounted to continued scenes of frenzied destruction caused by projectionist gaffs and how to safely deal with such situations. “Don’t open the canister,” an overly calm voice intoned. “It’s too late. The decomposition cannot be arrested.” We were not engulfed in insatiable chemical flame that weekend. In fact, there was not a single serious glitch in the projection of any of the films. The audience applauded the projectionists at every screening, as they ought to, grateful for the survival of both the prints and themselves.

Just a few days later, seeing reel after reel of nitrate film comically combust on screen no longer seemed funny. It seemed downright tragic.