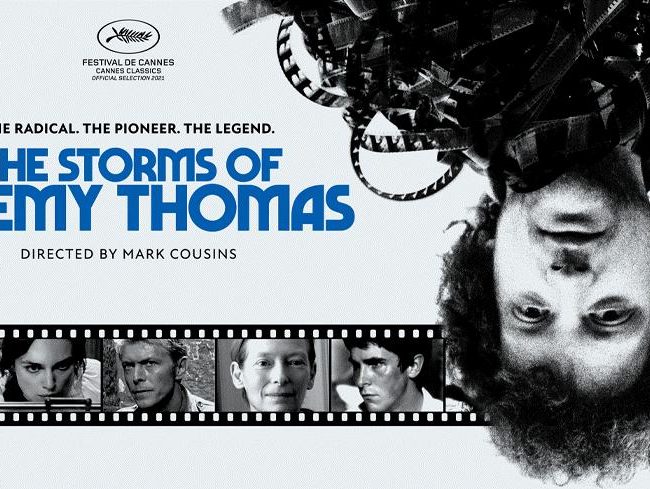

SALESMAN

(Beginning Friday January 26, Metrograph will present a one-week, 50th anniversary revival run of Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin’s Salesman, in a new restoration in partnership with The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences. )

“The best seller in the world is the Bible for one simple reason: it’s the greatest piece of literature of all time,” Paul declares at the open of the Maysles Brothers and Charlotte Zwerin’s Salesman, a seminal portrait of him and other scripture dealers. While the literary merits of the Good Book are just about the furthest thing from the film’s mind, their use as a point of departure highlights the documentarians’ prodigious ambition. By Albert and David Maysles’ own admission, they had set out to make a cinematic equivalent to Truman Capote’s 1966 (and, indeed, best-selling) magnum opus In Cold Blood, a nonfiction tome as narratively and psychologically engrossing as any novel. Form may thus appear to have preceded content, except that the Maysles were acutely aware that their literary model hinged upon its cast of characters.

Needless to say, they hit gold with the four salesmen about whose peregrinations across America the Maysles’ made fashioned an idiosyncratic road movie. All four are Boston Irishmen working for the Mid-America Bible Company. They also each carry a spirit-animal nickname that amplifies Salesman’s approximation of an adult fairy tale. Paul Brennan, “The Badger,” is a arthritic straight-shooter bearing no small physical resemblance to William S. Burroughs. Charles McDevitt, “The Gipper,” is a bit more heavy-set, and even less sure of himself. With his wispy, awkwardly elongated bowtie and short-sleeved shirts revealing his thin, hairy wrists, James Baker perhaps most visibly deserves his moniker, “The Rabbit.” Raymond Martos, “The Bull,” meanwhile, wears his hair slicked back and looks the closest to a “closer,” to borrow a term from Glengarry Glen Ross, one of countless works inspired by the documentary.

The real singularity of Salesman, though, is its atmosphere. In the first half, motel rooms in disarray and incontinent snow suggest an apocalypse or day of judgment on the horizon. The men’s world seems to be falling apart at the seams — something they have a good laugh discussing in one indelible scene, with Paul guffawing about how squarely their lives are “on the fringes.” Eschatological tones subside, however, as the film moves to the overdeveloped and sickeningly saccharine areas of Miami Beach and Opa-Locka — a veritable purgatory on earth.

Between heaven and hell seems the only right place for the salesmen, as out of place as they are in those Floridian enclaves. They cobble together a living superficially encouraging pious study, while they spend their downtime smoking, gambling, and mulling over their plain avarice. The sacred goods they’re pushing are considerably profane: opulent, deluxe editions that are meant to reaffirm faith in those whom society has largely neglected. The books are to the working class on the cusp of the junk-bond era what indulgences were to elites in the Middle Ages, and the salesmen are about as predatory as the Catholic Church has ever been. Yet we reserve some sympathy for them, not only for their everyday victimhood in the rigmarole of materialistic American society, but also for their easy rapport with the housewives and other family members whom they visit, door-to-door.

What makes a documentary classic? This seems an important question given how few are still watched in an era when no one could keep up with all the new releases. One criterion seems to be a film’s ability to evoke incredulity on first encounter and point to a cinematic depth that rewards further viewings. To the latter, we could attribute the mercurial lighting and shooting style. The handheld camera, quivering unnervingly, rarely retreats from the men’s hulking shoulder blades. Salesman also tapped into the zeitgeist. Death of a Salesman premiered on Broadway in 1949, running for a critically and popularly acclaimed twenty-one months, then traversing both stages and screens around the world. In the year before the making of Salesman alone, there were two TV adaptations of Death of a Salesman, one on CBS starring Lee J. Cobb and another on the BBC with Rod Steiger in the lead. Salesmen may have been a dying breed, but the desperation encircling both their prey and them, as predators, may be one of America’s clearest qualities.

– Joseph Pomp (@pompqmoq)