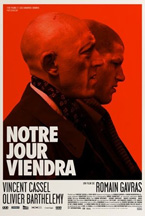

(Our Day Will Come next screens at the 2011 Edinburgh International Film Festival on June 17 and 20. Visit Romain Gavras’ Vimeo page to watch his commercial and video work.)

Romain Gavras is an instigator. His music videos—specifically ‘Stress’ for French duo Justice and last year’s ‘Born Free’ for M.I.A.—have been banned on French television and YouTube, giving him the reputation of enfant terrible, one with panache and abandon. These videos shocked for good reason; ‘Stress’ feels like a first person account of a mugging while ‘Born Free’—though it overshadowed the song and the commotion nearly dwarfed the video itself—is overwrought, truisms writ large, bolstered with unearned gore. With his first feature film Our Day Will Come (Notre Jour Viendra), Gavras again shocks and awes, though this time to his credit. Our Day Will Come is a hedonistic nightmare, one that explores how quickly power and the pleasure derived from it turns into rage and terror.

There are two redheads. One is Patrick (Vincent Cassel), an apathetic middle-aged therapist. The other is Rémy (Olivier Barthelemy), a tortured, introverted teen. Rémy’s preoccupations and mood swings show a person who’s never been allowed to be himself and thus doesn’t know who he is. Patrick could not know himself better. He understands that life is boring, that talking people through their problems toward new ones is futile. Both crave change and action. One night, Rémy is pushed to violence and hits his mother and sister. Afraid of the consequences, he flees. On a midnight drive to nowhere, Patrick finds Rémy and saves him, taking him far away.

Patrick, in every way the propeller, the puppeteer, creates each event according to his whims and imagination. He sees the frustration and hatred that sits, waiting, just beneath the surface in Rémy and teases it out effortlessly. Why? For his own enjoyment? Because it’s real? Because he can? Patrick hates because there are things he cannot love. He is bored because things do not excite him. He must make his own fun, create his own meaning. In Rémy he does not find a companion so much as a sieve, a pair of limbs, though one with its own conscience, and grievances.

Rémy believes that he is persecuted because he has red hair. Though this is a metaphor, one that includes all degraded minorities, it is true that in England and elsewhere in Europe people with red hair are ridiculed and ostracized (‘Gingerism’). While in a grocery store, Rémy sees a sign, a life-size cut out of a family of smiling redheads—Ireland. From that moment Rémy is given a purpose, to make his pilgrimage to Ireland, where he will finally be with his own kind, free from tyranny.

Rémy believes that he is persecuted because he has red hair. Though this is a metaphor, one that includes all degraded minorities, it is true that in England and elsewhere in Europe people with red hair are ridiculed and ostracized (‘Gingerism’). While in a grocery store, Rémy sees a sign, a life-size cut out of a family of smiling redheads—Ireland. From that moment Rémy is given a purpose, to make his pilgrimage to Ireland, where he will finally be with his own kind, free from tyranny.

Patrick is skeptical but Rémy’s newfound ardor is welcomed and so he humors him. The two drive north, through an industrial landscape that constantly feels like the outskirts of somewhere else. Director of Photography Andre Chemetoff casts them out into a world of muted greys, of empty parking lots and unending stretches of highway. They venture from town to town, with Rémy’s confidence growing with each new experience, his grasp of reality diminishing in turn.

Rémy buys new clothes and a crossbow in the hope of reinventing himself before his arrival in his new home. Walking through a small town with the bags of clothes and a trench coat hiding the crossbow, he spots a redheaded teen walking toward them. He runs over and begins to harangue the boy with a diatribe describing a better world, of the tolerance and acceptance that’s around the corner. The boy is not only confused, but terrified, of this much bigger kid holding him by the neck, telling him what to think. Here Patrick realizes what’s happened, and what they’re heading toward. Rémy gives the boy a shirt, tells him to be brave, that a change will come soon. The kid runs away bewildered—the enemy is not everyone else, it’s paranoia, it’s you.

From there, things descend into utter depravity. Through a perverse affection, Rémy and Patrick one-up each other, with every act making them more entwined, and more destructive. After a brief chase down a cobblestone road, Patrick and Rémy accidentally find themselves in front of a wedding party leaving the church. For once, Patrick is out of ideas. He does not know if he wants to run, kill them, himself, or to give up right there, and just go home. ‘You two kiss each other,’ he says, pointing to two old men. At first in disbelief, the men are forced to concede and begin to kiss. ‘Come on! More tongue!’ Patrick yells. It’s clear that Patrick has no plan, never had one. He was trying to destroy everything he could—strangers, Rémy, himself—without motive, barely with conviction. Patrick loves Rémy and so wants the best for him, but what is ‘best’? To Patrick, it’s truth. Is what they’re doing true? It’s not clear. But it does have consequences, and so, it is real.

Our Day Will Come is a film with a murky moral compass. It’s difficult to denounce the characters for their actions because it’s not clear what they, or the director, think about them. With this ambiguity, Gavras gives us the power to form our own opinions and though some will denounce the film as dissolute, perhaps we’re just being shown that this kind of violence is always right there. You just need to look for it.

— Jesse Klein