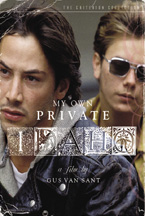

(My Own Private Idaho was released in 1991 and is now available on DVD through Criterion. New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles screened it on August 31st and September 1st, 2011.)

Gus Van Sant is a curious one. No other director, save perhaps the supposedly soon-to-be retired Steven Soderbergh, has moved as freely and frequently between the mainstream (Good Will Hunting, Milk) and the avant-garde (Elephant, Last Days) in the last two decades, making Van Sant as familiar a presence on the festival circuit as he is at the box office. What immediately stands out about My Own Private Idaho, especially in looking back at it a full two decades after its release, is how it melds the more experimental sensibilities of its director’s “strange” movies with the star power of his “normal” ones. Van Sant has worked with the likes of Sean Penn, Sean Connery, Robin Williams, and Matt Damon throughout his career, but almost always on larger, more straightforward projects. And while it’s true that neither Keanu Reeves nor River Phoenix were yet the stars they would one day become (the latter in memoriam), Phoenix had already scored an Oscar nomination and both actors were clearly on an upward trajectory that, for Phoenix, was tragically cut short. It’s tempting, in retrospect, to think of the movie as a sort of pre-emptive elegy for the young actor, but this view quickly proves reductive and even dissatisfying. Everyone in this film is wandering, whether toward or away from one another, but few understand their plight well enough to change it for the better.

My Own Private Idaho is first and foremost a road movie. It’s also a loose adaptation of parts of Shakespeare’s Henry IV and V in which a homeless kingpin replaces a portly knight and a gay street hustler stands in for to the heir to the throne. If this all sounds exceptionally strange, even for Van Sant, it is. But it’s also one of his most visually sophisticated outings to date, as well as an exceedingly interesting take on (and departure from) its source material. The actors are frequently posed in static sexual positions, with Van Sant jumping between several shots per second in strangely affecting, still-life montages; the sky moves sideways and backwards over unmoving landscapes; and, as an effect of all this, we’re made to feel not unlike the narcoleptic Mike as he drifts in and out of consciousness. This is all in service of Van Sant’s portrayal of physical and spiritual homelessness, of constant movement masking inertia within. My Own Private Idaho is populated by orphans, prodigal sons, and other lost souls for whom dancing around a trashcan fire or painting other peoples’ families while living in an RV is an adequate substitute for maintaining bonds with one’s own family.

Nearly everyone in the film does whatever he (and, more rarely, she) can do to distract himself from this fundamental loneliness, and often these diversions are sexual. So unlike, say, Elephant and Last Days, whose homosexual acts seem out of place and perhaps even just thrown in for the hell of it, the tendency among the men of this film to turn to each other for affection feels like a natural outgrowth of their fraternal bonds—they’ve no one else. This is especially true of Mike and Scott, but even here there’s a rejection: Mike makes himself as vulnerable as can be—at a campfire no less; as with an allusion to a man getting shot while watching Rio Bravo, this seems an intentional subversion of the cowboy myth which may be seen as a sort of thematic forerunner to Brokeback Mountain—and is again left out in the cold. It’s one of the few times we see him truly reach out, but far from his only disappointment.

Nearly everyone in the film does whatever he (and, more rarely, she) can do to distract himself from this fundamental loneliness, and often these diversions are sexual. So unlike, say, Elephant and Last Days, whose homosexual acts seem out of place and perhaps even just thrown in for the hell of it, the tendency among the men of this film to turn to each other for affection feels like a natural outgrowth of their fraternal bonds—they’ve no one else. This is especially true of Mike and Scott, but even here there’s a rejection: Mike makes himself as vulnerable as can be—at a campfire no less; as with an allusion to a man getting shot while watching Rio Bravo, this seems an intentional subversion of the cowboy myth which may be seen as a sort of thematic forerunner to Brokeback Mountain—and is again left out in the cold. It’s one of the few times we see him truly reach out, but far from his only disappointment.

Mike travels from Portland to Seattle to Idaho to Italy in search of his mother, but the more revealing journey is the internal one as he struggles to formulate a concept of home that makes sense to him. “Been tasting roads my whole life,” he says while looking over a vast expanse of blacktop in the Potato State; for him, both directions represent possibility as much as they do potential (and probable) disappointment. Mike’s most notable trait, his narcolepsy, serves as an internal alarm, a way of avoiding confrontation with distress related to his mother. The tic is useful to the viewer in that it heightens our awareness of stressful situations and makes it clear early on what eats away at Mike, who so often tries to hide his true feelings from those closest to him and even from himself. Van Sant mirrors this visually via frantic cuts between his characters and the land they’re both bound to and constantly trying to escape.

The complex dynamics between Mike, Scott, and nearly everyone else they come across only deepen this sense of filial abandonment. My Own Private Idaho is not only about absent parents but, on the other side of the coin, wayward sons. The two leads’ relationships with their parents throw this into sharp relief: while Mike was abandoned by his parents, Scott has voluntarily drifted from his wealthy father in order to live his own life—at least until his inheritance arrives. Though reversed, their situations are essentially the same insofar as both feel a lack that, though shared, doesn’t bring them any closer together. Scott eventually sees the full extent of his friend’s longing and, rather than attempt to bridge that gap, turns away from him.

The film ends with two very different funerals—one stately and restrained, the other jovial and celebratory—for Scott’s two fathers: one biological, the other chosen. Having made his choice to abandon one in favor of the other, his final thoughts are hidden from us behind his calm, searching eyes. These dual (and dueling, as they take part simultaneously and within a few dozen yards of each other) burials embody the mourning of Scott’s loss but also point toward the fact that Mike never even had what his former friend has just now said goodbye to.

— Michael Nordine