Listen to Me Marlon

“I didn’t make any great movies. there’s no such thing.

There are no artists. We are businessmen, we are merchants. There is no art.

Agents, lawyers, publicity people… it’s all bullshit… money, money, money —

you think it’s about something else? You’re gonna be bruised.”

There was a distrust of Marlon Brando, from his earliest entrance as a kingfish in the broad spectrum of 20th century cinema. His method, terrifying and new to the culture at the time, was alternately observed in curiosity and awe by the adoring public, as were his Italian features, and in the same instance, viewed as a threat. He was reviled by studios and paparazzi, and dragged through the mud on numerous occasions in his seminal, storied trajectory, only to emerge with a more interesting response and new performances in answer to his detractors each time. Characterized publicly as an a duly-labeled enfant, he was most terrible in every sense, but only when understood as much more than the childlike manipulator he would be repeatedly painted as. While there was much of him that may have appeared the same on the inside as it was when he was a child, his work was anything if not filled with mystery and innovation of form and character, even in his missteps. He trusted no one, felt abandoned by all. The world may have gazed and swooned over the ripples in his T-shirt, the beads of sweat so explicitly lit, the martyred masochist with a blackened eye, a split lip, but for every prurient embodiment that Brando displayed, for every pornographic element, it was always the sense of something behind his eyes, some mystery gift, seething and waiting to pounce, and it was exactly this animism that inspired such a devoted following. The audience may marvel at the delicate poise, but it is the control by which they feel hypnotized.

“that’s a wind you can trust. you are the memories.”

The only way to truly trust in the message you are receiving is to get it from the source. Stevan Riley’s study of Brando through his own words, Listen to Me Marlon, made for Showtime and premiering at New Directors New Films 2015, takes this to heart and runs the gamut. As comprehensive as it is sprawling and interwoven chronologically, Riley’s film utilizes a trove of personal and private voice recordings made by Brando on location and in his various travels, as well as at his homes in California and Tahiti. Coupled with a ghostly digital replication of Brando’s disembodied head, speaking from a pixelated, antiquated digitized realm, along with ample examples from his work, the seen and forgotten, the ghost-narrator effect used to similar disquieting spells previously in A.J. Schnack’s About a Son is captivating. The audience is drawn instantly into this world with Marlon as our guide. If Brando was anything, he was many, but more than his outward personality, his voice is gentle, compassionate, and inspiring to hear.

It’s truly a pleasure to sit and listen, as a captive audience, to the source. The day after his death in 2004, Rick Lyman wrote in the New York Times, “Simply put, in film acting, there is before Brando, and there is after Brando. And they are like different worlds.” It is hard to imagine the same can be said, will ever be said, about another performer. Of his objective, Riley’s Brando would say, ”I wanted very much to be involved in motion pictures, so I could change it, and bring it something closer to the truth. And I was convinced I could do that. At night, I think about it, dream about, and I wake up– absorbed by it. I wanted to make pictures that were meaningful to me… to stop that movement from the popcorn to the mouth. Get people to stop chewing. The truth will do that. And damn, damn, damn, damn, when it’s right, it’s right. You can feel it in your bones.” These are words from different time periods, recorded in sporadic steps and intervals throughout his life. And yet it reads, as Riley hears it, as one sentence: a life sentence. Some would say they broke the mold when they made him. Marlon would say he broke it with his own bare hands.

“I had a strong sense that I had to be free. standing on that train, I was free.”

The pain of family is always there, in each of his performances. Stanley’s struggles with Stella become unbearable, with Brando’s Polish laborer lashing out at even the inanimate in his nostril, frustrated, impotent rage. Terry Malloy’s seething resentment of the corruption in his brother Charley’s eyes comes boiling over. In Arthur Penn’s The Chase, a sadly overlooked masterwork, Brando’s Sheriff Calder admonishes his wife, “I’m not gonna bring children up over a jail.” Born in Nebraska and ready to bolt almost as soon as he could stand, Brando’s upbringing factored more into his formative skillset than most still realize. His father Marlon Sr.’s uproar, an abusive, caustic, belittling personality, was coupled with the rebellious, unashamed Dodie, his alcoholic, mercurial mother. As a man, his resentments and conflicted devotions towards his upbringing and his kin (“I played the loving son, they played the adoring parents. When what you are as a child is unwanted, unwelcome, then you look for an identity that will be acceptable. I had a wide variety of performances that were in me”) were planted and nurtured early on, if nurtured is even the correct term that can be used to describe what happens when seed gives root to trauma.

Brando’s inability to reconcile his role as a misbegotten son, a perennial disappointment to his father, even at the most obvious levels of success, along with his own struggles to correct the pattern through fatherhood, made for the cauldron in which a potion an entire culture drank from was brewed. Perhaps his greatest sin, as he imagined it, was that failure, of never being enough for a family. They were, as his disciple James Dean screamed, years after Brando crawled into a wheelchair and onto American screens for the first time, tearing him apart. Of his father, Brando said, “…he was a man with not much love in him…” By the time Brando was ready to direct something of his own, the wrestled-from-the-hands-of-Stanley Kubrick One Eyed Jacks, there was only one name for the villain in his picture: Dad.

As he would speak of years later, Brando experienced a great horror at repeating his father’s mistakes, at allowing the poison he consciously sensed within himself to spread. He was aghast at the prospect of infecting his own with the same curse. Obsessed with it. In his words, “I didn’t want my father to get near Christian. Because of the damage he did to me, I said ‘he’s never going to get near that child.’” Years later, when Christian Brando shot and killed his sister Cheyenne’s boyfriend at their father’s home, the prophecy fulfilled itself, the circle closed, and it became painfully obvious to anyone who knew, that Marlon’s worst fears had come true. Christian, who by all accounts, although clearly troubled, was kidnapped as an adolescent by his mother, sold to Hippies on some hillside in Mexico, and left to nearly expire from pneumonia, the disease that eventually killed him at 49. This was not the life his father had wished for him. And yet, it couldn’t help but feel to Brando, that finally, the curse had come home.

“We’re always hiding things…I was always trying to guess,

those things about themselves that people do not know about…”

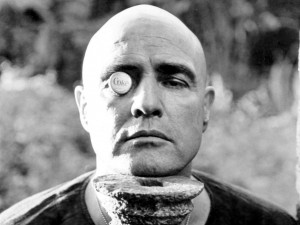

If the father is the shepherd of the flock that is his brood, Brando’s Colonel Kurtz described his own characters and children better than even he may have realized it: “…like lambs to the slaughter.” Brando managed to permeate every pore and ripple of a life, to find the inequity therein and exploit it, in every performance he gave, and no matter how theatrical or downright ridiculous many of them may seem in hindsight, there is so much to be gained from each, still. His legendary characters and moments didn’t interest him as much as Kurtz, but maybe because Brando was reticent to understand that while he felt like Marlowe up the river as well at that moment in his own life, he had always had the ability, no matter how far he pushed it from his own consciousness, to truly possess another being, to become possessed by one in turn, so that each of his men of tormented pasts could emerge, walking, like Sheriff Calder and Terry Malloy, bloody but not beaten, beaten but not bowed, bowed but never broken. Even those of whom he reserved only contempt (he once said of Stanley Kowalski, “I hated that character, and couldn’t identify with him…”), there was clearly a significant mass growing within him that did.

While he refused to accept it, Marlon had a magnetism to the way he stepped into the shoes of brutes that was both beast and prey, that was forged in a dynamo of men he despised, and a confluence of his own spite and mimicry. Describing his first viewing of his own performance in Kazan’s On the Waterfront as “so embarrassed, so disappointed” the one thing that can be trusted is that the parts that made him wince were the parts that always managed to hit way too close to home. Too close for comfort. So close they were, sadly, uncanny. Years after his first Oscar he would proclaim of the most famous of scenes from Kazan’s film, “there’s times when I know I’ve done much better acting than that scene in On the Waterfront. It had nothing to do with me. The audience does the work. They are doing the acting. Everybody feels like a failure, like they could have been a contender.”

This emphasis on the universal was not some hack-eyed slant on the song-and-dance-man routine or the hardboiled cereal box stars of the matinees, not some new play on the old tried and true cast of familiar character traits. There is often something pointed out in his work, referred to as rebellious. There is nothing rebellious about any of Brando’s characters. There is instead everything that is mutinous about them. This child doesn’t want to rock the boat. He wants to capsize it. “Hey! I’m not your fucking stamplicker, and I don’t care if it does cost me my job!” He’s taking command of this ship and going down with it, unless you want to try and stop him. I’d wager you might even join up, enlist in the ranks of his insurrection, if only to watch him hold court, mesmerized, as we are by those who would say, as Kowalski does, leaning in so close Blanche can smell his breath — “Ha, ha!” To speak truth to power, wherever it may be. “Whaddya got?”

“when a camera is close on you, your face becomes the stage. your face is

the proscenium arch of the theatre, 30 feet high… and it sees all the little movements of the

face, and the eye, and the mouth… You have the intensity to act.”

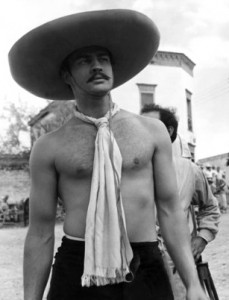

For a man who equated his line of work with dishonesty, a kind of swindling specified only in the most daring of capers, (”You’re lying at the speed of light, you’re lying to save your life. You lie for peace, you lie for tranquility, you lie for love…”) Brando managed to reach for the devil in the details of each of his characters, and to invest himself in honesty just as much as he would purport to be equally involved in deception. He sought refuge in places as far from the horror and moral terror he found in American small-towns and bloodthirsty inhabitants, Hollywood chief among them, finding some solace in the idyll of Tahiti on location for the worst experience of his filmmaking career thus far (Mutiny on the Bounty), one which the tabloid media spared no expense to exploit for salacious, often libelous headlines.

What did he expect? He had long since first thrown his wrench into the gears of the system, and while the charges of “holding up productions, costing millions” flew repeatedly, what it was in actuality was that Marlon just saw that his wrench did little. When that failed, he threw himself into the apparatus, headfirst to slow down the machine. Of the Tahitian people, Brando could see no such dishonesty. “They had unmanaged faces, unmanicured expressions, a kindness…that’s where I want to go, that’s where I want to be.”

Brando didn’t care. He didn’t care for the majority of things the greater public both needed him to in order to be fully accepted as one of them, and in fact relished in his refusal thereof, vicariously embodying his rage and quick step to uprising. He developed his own path, his own moments, and took them, with the same cunning as he would attack a scene. His process was warlike. “You have to look at the cameraman, the producer lurking in the corner, and say, ‘I don’t give a fuck about any of you.’” Carry a sign at a protest that says, “Marlon Brando is a Niggerlovin Creep,” see if he cares. He’s still gonna get up there and say, “That could have been my son.” There’s a moment in Riley’s film where an offscreen interviewer asks a stoic Brando of his involvement in MLK’s protests in Selma: “Have you considered the fact that you might suffer bodily harm yourself?” There is a silence. It seeps out of Brando. He remains still, stoic, then nods, then smiles, laughs, exhales, and looks Death in the eyes of the Interviewer, replying coldly, “Yes.” You could hear the pins drop across state lines in his silence. You fool, he is thinking. These are my people. I don’t care. You still don’t get it. This is worth it to me. To watch the sequence of Brando in Tahiti, his Xanadu, is to see someone truly at peace, far from what he refers to as “the nightmare of the white man, the nightmare of the want of things…” These were the nightmares he faced at home, that he could not rid himself of, that he feared for his own loved ones to traverse in the same difficulty, and what exactly he saw the Tahitian islanders as liberated and so inspired from, in the absence of that nightmare from which he never fully seemed to wake.

“You’ve got to be somebody, if you’re not anybody, you’ve committed a sin. You’re on your own.

A neurotic individual’s entire self-esteem shrinks to nothing if he does not receive admiration. To be admired and to be respected is a protection against helplessness, against insignificance. Because he’s continually sensing humiliation, it will be difficult for him to have anyone as a friend.“

Riley’s portrait of Brando creates a new Marlon, one of which he himself refers to (seemingly prescient in light of last year’s The Congress) as simply “Watch! It’s gonna happen!” An encapsulating, experiential series of vignetted audio, the effect we are left with is that of being no longer admirers from afar, but almost strangers who’ve stumbled cross an album snapshots, pictures of a performer’s story in his own words, his own narrative. That it is as seamless a patchwork of thoughts is to be recognized as Riley’s steady hand and perfect pitch, though the original skillset for such a woven tale still lies in the subject first and foremost. Marlon could see into his crystal ball in a lot of ways. Listening in on his own recordings feels at times too close, too bright. Like he knew we’d be here one day listening and decided to crank the heat before he left.

– Evan Louison