(Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair is the unrated combined print of Kill Bill Vols. 1 & 2 that screened at Cannes in 2003 and has since been unavailable. New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles is screening it from April 3-7, 2011.)

Kill Bill needs no introduction, but this version of it might. Originally conceived as one film, Quentin Tarantino’s vengeful opus was nonetheless released as two due to its four-hour running time. This decision upset many; it was seen not only as compromising the director’s vision but also as a calculated attempt by Miramax to double dip. Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair may thus be seen as the “true” version of the film, one that’s been promised (though never delivered) as a special DVD release for years now. New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles—a repertory house Tarantino saved from going under last year—put an end to the anticipation by premiering The Whole Bloody Affair on March 27, Tarantino’s 48th birthday. Having now seen both versions, I feel fairly confident in deeming this the better of the two, though not without qualification.

For one, substantive differences between the two iterations are few. Among them: The Whole Bloody Affair‘s Crazy 88 sequence isn’t in black and white (the MPAA hogwash which forced the change to the theatrical cut doesn’t apply here), though, in truth, it may have functioned better that way; the cliffhanger that ends Vol.1 and the prologue that opens Vol. 2 are elided in favor of an intermission. There’s no “blending” of the two parts, as one might have hoped, and, as such, the film still consists of two clearly identifiable halves. That in mind, splitting Kill Bill was not without its merits. The six-month gap between the two films imbued Vol. 2 with an emotional weight that’s hard to replicate with a 15-minute intermission. The first scene in particular—in which we finally see how and why Bill did what he did at that lonely chapel in El Paso—was made especially powerful by the wait. Time lends any revelation more significance, something best captured by the two-film version.

In watching The Whole Bloody Affair, however, one gets a clear sense that this is how the film was intended to be seen. Its 247 minutes seem likely to try even the most devoted cineaste’s patience, but Tarantino’s narrative playfulness prevents the film from feeling as long as it is. He’s long been known for his uncanny ability to blend genres, pop culture references, and moods within a film (if not a single scene), but here the seamlessness of his cinematic alchemy is particularly impressive for how long it’s sustained. In this way, The Whole Bloody Affair takes on a symphonic quality; each line of dialogue and every shot is composed with the utmost intricacy and attention to detail.

In watching The Whole Bloody Affair, however, one gets a clear sense that this is how the film was intended to be seen. Its 247 minutes seem likely to try even the most devoted cineaste’s patience, but Tarantino’s narrative playfulness prevents the film from feeling as long as it is. He’s long been known for his uncanny ability to blend genres, pop culture references, and moods within a film (if not a single scene), but here the seamlessness of his cinematic alchemy is particularly impressive for how long it’s sustained. In this way, The Whole Bloody Affair takes on a symphonic quality; each line of dialogue and every shot is composed with the utmost intricacy and attention to detail.

More remarkable still is how little it ultimately matters whether Kill Bill is viewed in one sitting or two. It functions just as well either way. Regardless of how long the film in question is, Tarantino is capable of such trickery as drawing our attention to seemingly insignificant details—the name on a box of cereal, for instance—that ultimately become one of the most important things onscreen. Such meticulousness, as well as his continuous stream of homage, betrays the ecstatic nature of Tarantino’s films to which it’s often difficult not to respond.

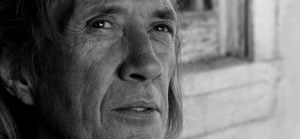

There’s a certain lyricism to be found even within the harshest moments of a Tarantino movie, something embodied most clearly by the beer-guzzling Budd, to my mind the single most fascinating character in Kill Bill. Unlike the rest of the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, Budd receives neither backstory nor the sense that The Bride feels particularly betrayed by him. Despite his negligible martial arts skills, he also (spoilers herein) comes much closer to killing her than his fellow assassins and is the only one on The Bride’s list whom she doesn’t dispatch personally. Budd’s descent from world-class assassin to bouncer at a strip club shows itself in the lines on his face and the rasp in his voice, and his years spent living in an isolated trailer in the California desert have inspired a certain amount of reflection:

“I don’t dodge guilt and I don’t Jew out of paying my comeuppance. We deserve to die, and that woman deserves her revenge.”

Among the countless memorable lines spoken throughout Kill Bill, this seems to be the richest. Michael Madsen delivers the words with such far-off resignation in his eyes and voice as to give the line the air of a soliloquy-in-brief. It distills much of the film’s subtext, but is neither ham-fisted nor maudlin in so doing. Budd is perhaps more self-aware and resigned to his fate than any other character in the film; his death is somehow tragic and something of a relief. A survey of the rest of The Bride’s victims, though prodigious, is unlikely to yield the same degree of wonder and grief.

— Michael Nordine

Corduroyfrog

I own part 1 and 2 .Is it worth me seeing this? is there any differences apart from the black and white ?

Slayme

Yes. The cuts from the end of pt1 and beginning of pt2, extended anime sequence and an cut scene of Bill fighting a gang when he first brings The Bride to Japan. I think several other scenes have been extended as well.

Mick A Noya

The Bill fighting the gang deleted scene is NOT in this long cut. People have created “fan edits” of the cut including the scene, but the scene is not actually part of the cut. Currently, no true version of the cut is out in the wild, except for the one Tarantino showed himself at Canne and at his theater.