PIGS, PIMPS & PROSTITUTES: 3 FILMS BY SHOHEI IMAMURA

(Pigs, Pimps & Prostitutes: 3 Films by Shohei Imamura is out on DVD today from the Criterion Collection. You can purchase it at Amazon.)

After a long period of being under-seen and under-appreciated in the U.S., the films of Nagisa Oshima and Shohei Imamura—the two giants of the Japanese New Wave—may finally be coming to the attention of a new generation of cinephiles. The career-spanning 2008 Oshima retrospective curated by James Quandt continues to travel around North America, and his ’70s provocations In The Realm of the Senses and Empire of Passion were recently released in handsome new DVDs by the Criterion Collection. Quandt also oversaw a landmark Imamura retrospective in 1997, and there’s been a slow trickle of Imamura DVDs in the years since. Now Criterion has brought out a box set collecting three of his early films, Pigs and Battleships (1961), The Insect Woman (1963), and Intentions of Murder (1964).

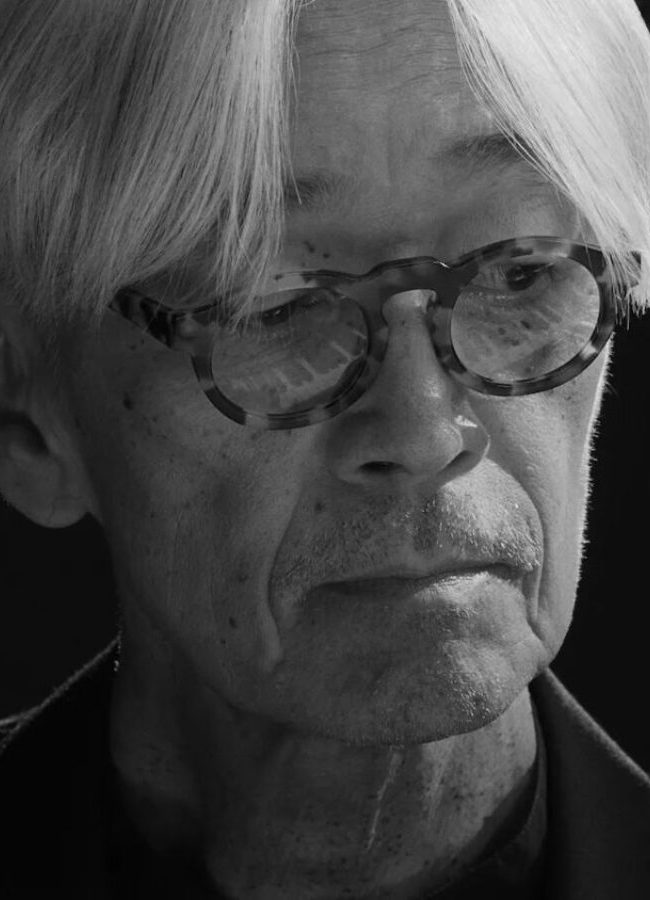

Imamura (1926-2006) was born into a middle-class family in Tokyo, and studied Western History at Waseda University, where he also dabbled in student theater and radical politics. As the post-war U.S. occupation began, he hustled cigarettes and alcohol on the black market, and hung out with bar hostesses, gangsters, and others on the margins of polite society. After graduation, he joined the assistant director program at Shochiku’s Ofuna Studios, working under Ozu on three films, including Tokyo Story. It’s a critical commonplace to suggest that Imamura’s distinctive cinematic vision was formed in reaction to, or rebellion against, the old master, but this may be overstating the case: Imamura would surely have developed his unique worldview even if he’d never trained with Ozu. Still, the contrast is a useful and revealing one. Ozu chronicled the everyday triumphs and travails of respectable Japanese middle-class life, registering each flicker of emotion with Zen-like serenity; Imamura would sing of the nation’s dark underbelly of prostitutes, pornographers, serial killers, and shamen, packing his frames to overflowing with thrusting, flailing, jabbering human activity. In an archetypal Ozu scene, the nuclear family might sit down to dinner, murmuring of this one’s troubles at school or that one’s wedding engagement. Imamura takes us around back to the outhouse, where the maid pukes up some bad food she ate while the pervy half-wit son dry-humps her leg. If Ozu is among the greatest of cinema’s humanists, Imamura is without peer in the way his films bring us into rude confrontation with our animal nature.

After a few years at Shochiku, Imamura switched employers. At the smaller Nikkatsu studio, he continued to assistant-direct and write screenplays for others, before finally being given a chance to direct in 1958. His first few films are nearly impossible to find here; most are reportedly impersonal studio assignments. But by the time he made Pigs and Battleships, his fifth feature, he had clearly come into his own. Kinta (Hiroyuki Nagato) is a mob flunky helping out with a scheme to supply the U.S. armed forces with meat from pig farms; his girlfriend Haruko (Jitsuko Yoshimura) works as a prostitute. They move through a world that’s utterly and irredeemably corrupt: everybody—the crooks, the cops, the citizens, the American soldiers—is for sale. Haruko wants Kinta to quit the gang and run away with her, but he refuses. Their hopes collapse at the end in a deadly shootout, as the pigs are freed from their pens and stampede through the streets.

After a few years at Shochiku, Imamura switched employers. At the smaller Nikkatsu studio, he continued to assistant-direct and write screenplays for others, before finally being given a chance to direct in 1958. His first few films are nearly impossible to find here; most are reportedly impersonal studio assignments. But by the time he made Pigs and Battleships, his fifth feature, he had clearly come into his own. Kinta (Hiroyuki Nagato) is a mob flunky helping out with a scheme to supply the U.S. armed forces with meat from pig farms; his girlfriend Haruko (Jitsuko Yoshimura) works as a prostitute. They move through a world that’s utterly and irredeemably corrupt: everybody—the crooks, the cops, the citizens, the American soldiers—is for sale. Haruko wants Kinta to quit the gang and run away with her, but he refuses. Their hopes collapse at the end in a deadly shootout, as the pigs are freed from their pens and stampede through the streets.

Pigs, like many of Imamura’s films, is tricked out with demented plot twists, near-slapstick clowning, and frenetic pacing—all the elements of farce, except it’s not all that funny. It has the high spirits of comedy, but it’s not a comedy. It’s not really a drama either. It’s a little of both, along with a crime thriller and a satire. Imamura tends to disregard most of the usual categories of genre and tone; his films are all over the place. He takes the same freewheeling approach to style as well, blending coolly detached long takes filmed from wide or medium distance with surging camera movements, dynamic compositions, and expressionistic distortion.

Another aspect of Pigs that would become an Imamura trademark is the contrast between genders: the man thinks big and talks tough but is a fool and a weakling at heart, while the woman sobs and suffers but ultimately prevails. Imamura’s women, though often crude, unprincipled, and irrational, possess a will to survive and a zest for life the men usually lack. (He once told the American film critic Audie Bock, “My heroines are true to life—just look around you at Japanese women. They are strong, and they outlive men.”) With the next two films in the box set, these women take center stage.

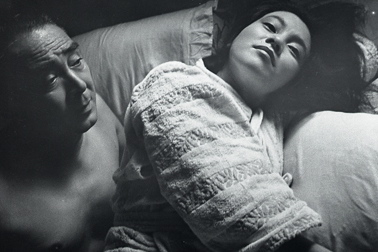

The Insect Woman spans nearly fifty years of Japanese history in telling the life story of Tomé (Sachiko Hidari). Born to a poor rural family, she becomes a factory worker and a union activist, then in turn an unmarried mother, a religious convert, a prostitute, and eventually a madam, only to lose everything and start over in middle age as a domestic servant. Lovers leave her, employees betray her, her daughter deserts her, but she perseveres. In outline, then, a “woman’s picture” of a type familiar to both Eastern and Western audiences. But the direct emotional engagement of conventional melodrama is tempered by the film’s blunt and bracing lack of sentimentality. Imamura shows us many sides of Tomé—that she’s a petty, selfish, and cruel woman, but also tender, devoted, noble, indominatable. By the end of her tale, this very flawed, fallen creature has grown into a great screen character. The Insect Woman is the jewel of the Criterion set, and one of Imamura’s masterpieces.

The Insect Woman spans nearly fifty years of Japanese history in telling the life story of Tomé (Sachiko Hidari). Born to a poor rural family, she becomes a factory worker and a union activist, then in turn an unmarried mother, a religious convert, a prostitute, and eventually a madam, only to lose everything and start over in middle age as a domestic servant. Lovers leave her, employees betray her, her daughter deserts her, but she perseveres. In outline, then, a “woman’s picture” of a type familiar to both Eastern and Western audiences. But the direct emotional engagement of conventional melodrama is tempered by the film’s blunt and bracing lack of sentimentality. Imamura shows us many sides of Tomé—that she’s a petty, selfish, and cruel woman, but also tender, devoted, noble, indominatable. By the end of her tale, this very flawed, fallen creature has grown into a great screen character. The Insect Woman is the jewel of the Criterion set, and one of Imamura’s masterpieces.

Intentions of Murder further develops the theme of women’s survival instincts. Sadako (Masumi Harukawa) is a country girl lorded over by her frail, philandering university-administrator husband and shrewish mother-in-law. After being beaten and raped by a burglar, Sadako’s initial reaction is to do what society expects: expunge the shame of her violation by committing suicide. But while preparing to kill herself, Sadako grows hungry and proceeds to dig into a hot meal; the food helps awaken a desire for more life. The rapist, a pathetic figure, equally as sickly as Sadako’s husband, develops an infatuation with her. They become lovers. In the end, the rapist is dead of heart failure and Sadako has grown strong, dominating the household which earlier dominated her.

As he did with Tomé, Imamura keeps us at something of a remove from Sadako—we’re sometimes plunged into her subjective POV, but more often we observe her from the outside, as if she were a specimen being examined under glass. Imamura claimed that as he was learning his craft as a screenwriter, he decided it was more important to study human beings than to study other films, so he began going to the library and reading deeply in anthropology, ethnography, and sociology texts. Presumably this led to the research-experiment quality that characterizes his mature work: the screen is aswarm with all manner of rages, freakouts, and frenzied couplings, but the director hangs back and records it all with a scientist’s coolness. (The Insect Woman’s original title translates as Entomological Chronicles of Japan, and the subtitle of 1966’s The Pornographers is Introduction to Anthropology.)

Unlike his great contemporary Oshima, who peaked with an astonishing run of films in the ’60s and early ’70s, Imamura went on to a long, prolific, and consistently fruitful career. Of his other films currently available on Region 1 DVD, I highly recommend two of his later masterpieces, the true-crime thriller Vengeance Is Mine (1979) and the period drama The Ballad of Narayama (1983). That still leaves many of his best films, including A Man Vanishes, The Profound Desire of the Gods, Eijanaika, and Black Rain, out of reach (unless you’ve got a VCR, laserdisc player, and/or all-region DVD player). But while we’re waiting for the gaps to be filled, this new box set provides a good place to start discovering or re-discovering the early work of this one-of-a-kind filmmaker.

— Nelson Kim