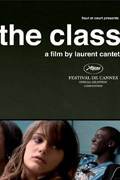

(The Class was picked up for distribution in America by Sony Pictures Classics. It is now available on DVD and Blu-ray. Visit the film’s official website to learn more.)

Quietly heartbreaking while maintaining both intimacy and reserve in its documentary aesthetic, The Class, surprise winner of this year’s Palme d’Or at Cannes, is the most accomplished film about modern eduction since Frederick Wiseman’s masterpiece High School. It is that all too rare movie that leaves our assumptions and prejudices thoroughly tested. Depicting one long, troubling school year for a French language class in a Gallic public school, Laurent Cantet’s follow up to his splendid Heading South is another meticulously crafted look at the intersections of class, race and culture in modern France. It effortlessly transcends the limitations of the classroom drama, be it The Blackboard Jungle or Dangerous Minds or even Half Nelson, and shows us with far reaching empathy the everyday challenges and failures of basic secondary education.

The Class hinges on a Caucasian teacher, Francois Martin. At first, Martin comes off as sympathetic and funny to his French class, yet he slowly loses the good faith and interest of his mostly black Caribbean and African students over the course of a full year. The students include a pair of unruly but sophisticated youngsters: an intelligent if often disruptive Arab girl named Sandra (Esmeralda Quertani), who reads The Republic in her spare time and has no interest in class, save antagonizing her teacher; and Souleymane (Franck Keita) a young and tough but insecure Malian with a hair trigger temper who thinks of Frenchness with nothing but contempt. Cantet takes us to a place where the children of poorly educated immigrants are too often left behind, asked to adopt a set of cultural practices and desires they clearly don’t see the significance of and whose own experiences, cultural or otherwise, are often disregarded.

Watching the film can provoke one to ruminate on a number of questions concerning national and cultural identity. In a world consumed by tribalism that wears many faces, what do notions of national and cultural identity truly mean? What are the mechanisms through which we are coerced into constructing such an identity? In the rapidly changing, multi-cultural societies of the west, and especially in France, these are questions with no easy answers. A country rife with religious and ethnic tension simmering from its working immigrant classes, France is an ex-imperial western nation state whose very imperialism is one of many factors that has led to a generation of public school children of various national identities. Their parents may be from any number of far-flung Caribbean, African, Eastern European and Asian outposts and who may have little or no working understanding of the dominant culture to pass onto their often hopelessly unmoored children. No film I’ve seen has driven at the heart of these matters and their lingering consequences with such humanity and incisiveness as this one.

Cantet, as has become his method through a series of the most devastating and socially engaged French films of his era, casts non-professional performers, chosen from the ranks of the actual French secondary school where the picture was captured in immediate and kinetic HD, and renders a world wholly authentic, where tired, confused and not terribly engaged students are paired with well meaning but ultimately hypocritical teachers, such as the one rendered with expert moral ambiguity by Francois Begaudeau, who is both a first time actor and the author of the book on which this film is at least partially based.

Cantet, as has become his method through a series of the most devastating and socially engaged French films of his era, casts non-professional performers, chosen from the ranks of the actual French secondary school where the picture was captured in immediate and kinetic HD, and renders a world wholly authentic, where tired, confused and not terribly engaged students are paired with well meaning but ultimately hypocritical teachers, such as the one rendered with expert moral ambiguity by Francois Begaudeau, who is both a first time actor and the author of the book on which this film is at least partially based.

Begeaudeau’s French instructor, just entering middle age, humorous and somewhat attractive, clearly wants the best for his students. But does he truly know what that means? Cantet gracefully never chooses sides or endorses one particular group of thoughts in the ideological conundrum that modern education proves to be. What good is there in introducing a group of children to a literature, a cultural heritage, that many feel little affinity to? Those that do, as witnessed in a crucial scene halfway through the film, in which one black student suggests to calls of outrage his affinity for the French soccer team, are often scolded and exiled by their peers on cultural grounds. Others, as illustrated by Sandra, find their own way toward western culture, regardless of the platitudes of politicians, good but failed intentions of professional teachers and biases of their classmates. Yet the most endearing and sobering lesson of this all too important film is that some children, as glimpsed in the film’s unforgettably simple and painful finale, will always fall through the cracks.

— Brandon Harris