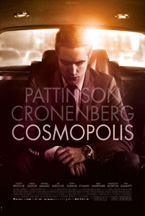

(Cosmopolis world-premiered in competition at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival.)

David Cronenberg’s much-awaited adaptation of Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis is a mesmerizing, utterly cerebral inquiry into the current economic crisis as channeled by its main character’s slowly imploding mind. At once a follow-up to eXistenZ in its portrayal of reality’s crumbling façade and A Dangerous Method’s kissing cousin by virtue of a non-stop blast of brainy talk, Cosmopolis is this year’s Margin Call for the philosophical-minded set.

The smartly cast (or is it expertly used…?) Robert Pattinson plays Eric Packer, a 28-old billionaire NYC asset manager who starts questioning the capitalist order of things, as well as spiraling down into the bog of existential fears. The movie’s dialogue-driven narrative has Packer engaged in a series of philosophical encounters, most circling around the idea of wealth, future and death. Fascinated with whatever remains tangible in the world of increasing digital un-realness, Packer spends much of the film heading to a barpershop in order to get an old fashioned haircut—all the time accompanied by media-spread premonitions of systemic political doom.

Packer’s odyssey into the capitalist heart of darkness begins in his state-of-the-art white stretch limo: cork-lined for extra privacy and equipped with pretty much everything money can buy, including a retractable urinal hidden beneath one of the multiple seats. Shot almost entirely from the inside by Cronenberg’s cinematographer Peter Suschitzky as a sort of vaguely Kubrickian space pod, it’s sealed shut from the outside world (which is seen mostly as rear projection, thus granting the whole setting a deliberately fake look of a Fantastic Voyage-like DIY futurism).

As Packer’s descent progresses, the crowds surrounding the limo start (quite literally) to rock the boat; anarchy creeps into the world and soon the snow-white car starts dripping with sprayed-on graffiti. The main character both avoids and embraces the chaos: overtly craving sex with his wife, covertly courting death and violence seen as pure acts impossible to appropriate by market economy, Packer grows increasingly unhinged and by the end almost begs for comeuppance. (The first premonition of the latter comes courtesy of one Pastry Assassin and takes form of a cream pie thrown in Packer’s face in a perfectly timed sequence of sudden slapstick.)

As Packer’s descent progresses, the crowds surrounding the limo start (quite literally) to rock the boat; anarchy creeps into the world and soon the snow-white car starts dripping with sprayed-on graffiti. The main character both avoids and embraces the chaos: overtly craving sex with his wife, covertly courting death and violence seen as pure acts impossible to appropriate by market economy, Packer grows increasingly unhinged and by the end almost begs for comeuppance. (The first premonition of the latter comes courtesy of one Pastry Assassin and takes form of a cream pie thrown in Packer’s face in a perfectly timed sequence of sudden slapstick.)

In his impeccable looks, unashamed commodity fetishism and seeming omnipotence undercut by sexual panic, Packer evokes both Mad Men’s Don Draper and American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman. The incessant talk he engages in, packed with pointed one-liners to chew on in many a post-screening discussion, he also resembles another late-capitalist misanthropist and doomsayer: David Thewlis’ Johnny from Naked. While one may be a disadvantaged hobo and the other all but a walking embodiment of plutocracy, the fact is they both relentlessly examine the world in which everything has its price-tag attached to it and—to use but one of Cosmopolis‘ numerous memorable jabs—“money started talking to itself” and became almost a form of abstract art. Given that last observation, it’s fitting that the film’s opening image is that of a fast-forwarded Pollockian paint-drip and the last is Mark Rothko’s blurried-pastel geometrical arrangement.

Cronenberg’s filmmaking here is both subdued and incisive. Humbly bringing DeLillo’s text to the foreground (although, as my Cannes buddy Simon Abrams told me, not without significant alternations), the film is nevertheless its director’s baby (and I don’t mean just the by-now-obligatory eye-stabbing). To borrow one of its own characters’ phrases, Cosmopolis is about “acquiring information and turning it into something stupendous and awful.” In other words, it’s about the world we construct for ourselves in our heads—as well as the perils inherent in the process. For all its talk of world economy, the movie pursues the same theme one of Cronenberg’s masterpieces did, which is to say that—just like in Spider—we’re once again sentenced for life to a solitary confinement within our minds and bodies.

— Michael Oleszczyk

Kanerwa

Bateman?And why not younger and more philosophical version of Wall Street’s Gekko?