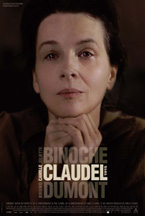

(Camille Claudel 1915 is now available on DVD and iTunes. It world premiered at the 2013 Berlin Film Festival. Distributed by Kino Lorber, it opens theatrically in NYC at the Film Forum on Wednesday, October 16, 2013. Visit the film’s page at the Kino Lorber website to learn more.)

There’s an underrated tradition of biopics that take varying degrees of creative license in portraying artists grappling with psychic afflictions, of which Vincente Minnelli’s Lust For Life, Maurice Pialat’s Van Gogh and Peter Watkins’s Edvard Munch are three salient examples. But who would’ve guessed that the reigning champion of French cinematic transgression, the aggressively unpleasant but always interesting Bruno Dumont, would choose to enter this mostly fanciful lineage with his first feature to boast the participation of a highly regarded actress (Juliette Binoche)? Camille Claudel 1915 also marks Dumont’s inaugural foray into overtly psychological melodrama, having made his name on metaphysical death trips in which grace is never far from horrific violence or uncharitably depicted sexuality. (His previous film, the mythopoeic and inscrutable Hors Satan, which was finally released in the US earlier this year, is arguably the most distilled summation of his shtick.) Despite the new aesthetic and thematic terrain he tackles here, rest assured that Dumont’s fingerprints are all over this one.

The plot of Camille Claudel 1915 unfolds over a few days in the life of the sculptress and former Rodin mistress (Binoche) as she awaits a visit from her God-crazy and more famous little bro, Paul (Jean-Luc Vincent), at the Montdevergues asylum where she is confined. Camille’s daily existence consists of preparing her own meals (a special allowance she has been granted by her doctor on account of her paranoiac fears that someone—Rodin, she suspects—is intent on poisoning her) and sketching in her room, with the occasional walk in the courtyard or pit-stop to pray at the chapel. She has countless run-ins with her clinically insane roommates and agonizes over the self-apparent cruelty of her persecution. But when Paul finally arrives on the scene (and after we hear him describe his Rimbaud-inspired fervor for the holy and/or supernatural), a colossal letdown for our suffering heroine is, predictably, right around the corner.

The plot of Camille Claudel 1915 unfolds over a few days in the life of the sculptress and former Rodin mistress (Binoche) as she awaits a visit from her God-crazy and more famous little bro, Paul (Jean-Luc Vincent), at the Montdevergues asylum where she is confined. Camille’s daily existence consists of preparing her own meals (a special allowance she has been granted by her doctor on account of her paranoiac fears that someone—Rodin, she suspects—is intent on poisoning her) and sketching in her room, with the occasional walk in the courtyard or pit-stop to pray at the chapel. She has countless run-ins with her clinically insane roommates and agonizes over the self-apparent cruelty of her persecution. But when Paul finally arrives on the scene (and after we hear him describe his Rimbaud-inspired fervor for the holy and/or supernatural), a colossal letdown for our suffering heroine is, predictably, right around the corner.

Dumont skillfully renders the monotony of Camille’s day-to-day, and he continues to display his own knack for translating physicality into purely audiovisual terms. The film’s lumpy and startling sound design effectively replaces superfluous images in a way that can only be characterized as Bressonian. Certain compositions recur frequently, albeit with slight changes, evoking a life drained of macroscopic novelty, one in which only slight deviations—a nun now standing here as opposed to there, a tree branch swaying in the wind slightly differently than before—can evidence time’s passage. Indeed, Camille’s point of view is rarely presented as anything but a series of impeccably lit still lives.

Binoche’s miserabilist tour de force of a performance introduces an element of psychodrama to Dumont’s system, a sharp contrast to the low-to-no-affect style he generally favors from his (non-)actors. Distracting from Binoche’s contribution is Dumont’s decision to populate the asylum mostly with actual mental patients. This lends the film a compelling documentary aspect, and it often plays like Through a Glass Darkly and Titicut Follies mashed together and topped with an extra dollop of material presence. But does this feat of stunt-casting constitute exploitation? Unclear, though the results command one’s attention too much to dismiss.

The introduction of Paul causes an otherwise psychological picture to become an intensely theological one. He falls back on Catholicism (not unlike the self-avowedly atheist Dumont) to justify the continued internment of his sister, and the possibility of Camille’s redemption is obliterated pretty much as soon as Jesus shows up. But Dumont refuses to advance a legible thesis on faith amid all of his usual sound and fury, likely because he has no desire to do so. Camille Claudel 1915 amounts to a departure that leads us right back to where we started, perplexed and intrigued.

— Dan Sullivan