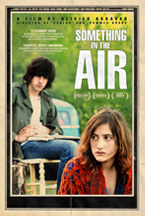

A Conversation With Olivier Assayas (SOMETHING IN THE AIR)

(Something In The Air is now available on DVD and at Amazon Instant through MPI Home Video.)

It seems I’ve been waiting my entire adult life to talk to Olivier Assayas, so having the chance to actually sit with him was a dream come true. In a career studded with highlight after highlight, from Cold Water to Irma Vep, Late August, Early September to demonlover, Sentimental Destinies to Summer Hours to Carlos, Assayas has demonstrated an incredible range and versatility in his work while maintaining his own voice, qualities that place him among the leading lights of contemporary cinema. We sat down during the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival to discuss his new film Something In The Air (Aprés Mai), opening theatrically on May 3, 2013, through Sundance Selects.

H2N: Prior to seeing Something In The Air, I read your book A Post-May Adolescence and while they are very much of a piece, the film’s point-of-view is very different. In the book, which, like the film, deals with the politics of the early 1970s, there are these lovely, funny ellipses in which every French leftist political group is derided for their shortcomings from a position of hindsight. But in the film, these groups and ideas are presented as of their moment, without hindsight or commentary. Can you talk about this difference in terms of writing this film versus writing the book?

Olivier Assayas: Well, I think they are completely different pieces that come from the same place. I could have somehow turned my book into a filmed essay or something; it would have been a completely different movie dealing with the period in a completely different way. I think that when you are trying to turn your autobiography into fiction, because that’s what happens when you make a film—you’re handing over the keys to the actors, you invent situations, etc.—you have to deal with the naiveté of the moment. When you are a kid—especially in the 1970s when everything was in turmoil—you are bombarded with emotions, ideas, contradictions, and somehow you try to feel your way through it. You’re not analytical; it would have been wrong or false to present my characters as too analytical or too ironic. They are absorbing things, they have trouble hierarchizing them, mostly because they are at an age when they have to define themselves. You have to find your path and they are trying; if you want to represent that, you have to present their confusion. So, the film has much more to do with the chaos.

H2N: What about as a director, your place in that? These are very personal politics and experiences, specific moments from your past that made it into your movie. It is about your life, and yet you seem a little bit unforgiving of yourself. You’re very skeptical of your previous points-of-view and the politics of the time. It feels almost regretful. Do you think there is regret there?

OA: That’s not the way I would put it because there is no nostalgia here. I am still somehow close to the rebellion of the times; it’s what made me whoever I am, it has consistently fueled my art at all stages. I am child of the ’70s. Absolutely. Which is a very special time because it’s not like the revolutions of the ’60s or the spirit of the ’60s here in the US. The ’70s were a crazy time; they were a really scary, dangerous time. You can be nostalgic about the summer of love or May of ’68, but I did not go for that. I lived through the ’70s and they were terribly conflicted.

OA: That’s not the way I would put it because there is no nostalgia here. I am still somehow close to the rebellion of the times; it’s what made me whoever I am, it has consistently fueled my art at all stages. I am child of the ’70s. Absolutely. Which is a very special time because it’s not like the revolutions of the ’60s or the spirit of the ’60s here in the US. The ’70s were a crazy time; they were a really scary, dangerous time. You can be nostalgic about the summer of love or May of ’68, but I did not go for that. I lived through the ’70s and they were terribly conflicted.

On one side, everything was possible because nothing was true anymore. You did not have anything solid to stand on. Everything had to be re-discussed, re-defined, re-invented. You dropped out of school, you didn’t want to have anything to do with family, you rejected bourgeois values. There was a sense of freedom, a sense that anything could be turned upside down at any time, which is not a feeling that kids today have because they have not lived it, they have not experienced it. For me, it was simple and obvious but I did not realize how unique it was.

In that sense, the echo of May of ’68 and what happened in May ’68 remains for me one of the defining moments of post-World War II Western culture. It is still a ray of hope that society can change, that modern society has the potential for change. What I am not so forgiving about are the politics that have never been my politics, which was basically French Maoism. Because of my political education—my father had been a militant anti-fascist and he was involved in anti-Leninist Marxist groups before the war, he had also been an virulent anti-Stalinist—he gave me reference points. Whatever I was, and I was involved in the politics of my time, but I was always extremely opposed to any totalitarian strain and there was way too much of it, scarily too much of it.

To me, it was really what spoiled it; the fact that the politics were wrong is ultimately what broke the hope of that generation. In that sense, there is no reason to be forgiving because it was very misguided to be tolerant of what was going on at that time. I am not only talking about China, where it was a disaster on a demented scale, but in general in Southwest Asia, not to mention the lack of a response about what was beginning to happen in the Eastern Bloc. French and Western leftists were infiltrated by Eastern European secret services and I did not hear them support the freedom movements in Eastern Europe; they would have been a vital help had they made that connection. But times change, and gradually of course you had a lot of support for those revolutions and movements, but not during the leftist years, the golden years of the left.

H2N: One of the things I appreciated in the film is this idea that the politics are, in fact, personal. A lot of people spoke of the collective, but your point-of-view seems to be the individual and their position in this, how to preserve yourself and your vision of the world…

OA: Yes, it is about ethics.

H2N: Yes, ethics. Each of your characters spins off into their own personal vision of how to best live a life that is true to their politics. Did the politics allow for this individuality?

OA: Well, you had to define yourself individually in terms of your politics. You had to. There was no choice. There is always a majority who just doesn’t care and especially because I grew up in the suburbs, you had a lot of the kids who were completely passive and had no idea what was gong on. But among the people who were involved in the energy of those times, you had to define yourself in political terms and the political debate in high school was virulent because it was completely cut off from reality. That’s why I call it a “Marxist theology,” because that was what it was about. But kids were fluent in that Marxist theology and it was extremely important for them to define themselves in terms of an anarchist idea or a Trotskyist idea like “what would have happened if Trotsky had had his way?” or “at what point did the Russian revolution take the wrong turn?” or “is the Chinese version of Marxist Leninism relevant? Is it something that can be exported?” This was a discussion on a daily basis.

OA: Well, you had to define yourself individually in terms of your politics. You had to. There was no choice. There is always a majority who just doesn’t care and especially because I grew up in the suburbs, you had a lot of the kids who were completely passive and had no idea what was gong on. But among the people who were involved in the energy of those times, you had to define yourself in political terms and the political debate in high school was virulent because it was completely cut off from reality. That’s why I call it a “Marxist theology,” because that was what it was about. But kids were fluent in that Marxist theology and it was extremely important for them to define themselves in terms of an anarchist idea or a Trotskyist idea like “what would have happened if Trotsky had had his way?” or “at what point did the Russian revolution take the wrong turn?” or “is the Chinese version of Marxist Leninism relevant? Is it something that can be exported?” This was a discussion on a daily basis.

H2N: And there is a tension between this situation and growing into an artist.

OA: Yes, of course. There was tension because everything was defined by how you positioned yourself politically. Right around the corner was a major change in society, the revolution. There was no doubt. It was not a matter of if, it was only a matter of when and how to get it right when the past had gotten it wrong. So, you had to project your politics into the future and you were learning constantly about the past. What all of this leads to is that, yes, it was extremely complicated to define yourself as an artist, to have any aspiration in that context, which was extremely collective. It was about shared hopes and meaning. You could have really violent debates with your friends about the finer points of your politics, but then, you were all together in your belief in the coming revolution.

Cutting yourself off from that was problematic. Also, I don’t know exactly how it was here in the US, I don’t know the balance—in France it was 75-25 in terms of politics versus counterculture. Counterculture was American and British, coming from London: punk rock, drugs, free sex, free press with the weird layouts. That was present, but it was very much in the minority in France and the different brands of Marxist politics were very much the majority. So, there was a sense of freedom and breathing space inside the counterculture. I completely adopted the counterculture, it was something that I was immediately attracted to because it was a form of rebellion against the bourgeois order, against the past, but in the name of ideas that felt more modern, that were of their time. It involved politics, but it also involved everyday life, it involved poetry, also a major change in the arts. There was this connection between art and rebellion, which made a lot of sense to me because the history of art throughout the 20th century had this relationship.

It was very difficult for me to have that idea accepted within the framework of French leftism. Leftists hated rock music, they only liked free jazz and were intolerant of other forms. They hated narrative movies; anything to do with American counterculture was tagged as “American” so it was evil. Drugs? Petit bourgeois. Music? Petit bourgeois. It was hard to find your position, because as a child of the ’60s, you believed in leftist politics. But you could also not help realizing how uptight and shortsighted they were.

H2N: Everyone in the film seems focused on tactics, but without the grand, overarching strategy or goals. For me, this felt like a very authentic portrayal of youth in a sense; we’re going to take to the streets! A 40-year-old factory worker doesn’t have the same tactical energy…

OA: Right. In the ’70s, you were on the battleground and in the fog of war. But who really had the big picture or who really knew the grand scheme? It was not very clear. All those Marxist groups, they all had a notion of the global strategy, especially when they were trying to connect rebellious youth with the workers, so they had a strategy, but it was just crazy. It made no sense. What they did not see was that it all had to do with the Cold War. When I was growing up, there was this notion that that Cold War division of the world was passé when actually, we were in the middle of it and we would not get out of it until the late ’80s and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

OA: Right. In the ’70s, you were on the battleground and in the fog of war. But who really had the big picture or who really knew the grand scheme? It was not very clear. All those Marxist groups, they all had a notion of the global strategy, especially when they were trying to connect rebellious youth with the workers, so they had a strategy, but it was just crazy. It made no sense. What they did not see was that it all had to do with the Cold War. When I was growing up, there was this notion that that Cold War division of the world was passé when actually, we were in the middle of it and we would not get out of it until the late ’80s and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Kids, specifically high school kids, were foot soldiers, not strategists or politicians. They were very far removed from the centers of command. They were pawns. Sure, what they were doing had to do with practical things; they were used to hand out fliers or tag buildings with graffiti, to be on the street and fight for the cause.

It’s also interesting when you mention the working class. Things were not divided in terms of class, they were divided by age groups. The whole obsession of leftism was to connect with the working class, but the middle-aged working class. The young workers were as crazy as us. It’s also the French education system. When you were in high school, you were confronted with every strata of society—the middle class, the lower classes, etc. You grew up with them, so you basically had the same ideas. There was no notion of money at the time, money was just not around. It is so striking when you look back at those times how little money we had to spend and yet, we spent it all on newspapers. [OA laughs]

H2N: In our country, the Vietnam War played such a huge role in the early 1970s political situation. The war is almost completely absent from the film and I am wondering what role it played in France? Was it just the example of evil American imperialism? France had its own role to play in that conflict from a very early stage…

OA: The anti-Vietnam War movement had already lost momentum. It was very important in the late ’60s and in France, there was not the same obsession as in the US because there were not a bunch of French kids going there and dying. For awhile, the anti-war movement was at the center, but because of the geopolitical divide of the time, it was coordinated by the French Communist Party and the Party was the enemy of the left. It could not be completely leftist, because of the Party. Their orders came straight from Moscow; even at the time it was transparent. In terms of the grander scheme of things, the battle was to fight the Communists in the factories, to break the Communist trade unions and impose new, leftist trade unions. You had leftist militants infiltrating the factories and exposing the Communists.

H2N: This film seems very much a companion to L’Eau Froide (Cold Water). Like that film, it seems specific to its time and very personal. Do you see your cinema as personal?

OA: It has to do with the connection with writing. I am a writer and filmmaker and if it amounts an autobiography like this film or Cold Water, I think it’s the same process as making fiction; you draw on your own experience, you show your relation to the world, it’s always something when you write. But I guess this film even more so, as this is as autobiographical as it gets. I’m using factual elements, but because I have already used this material in a dramatized way, it was important to me to de-dramatize this version, to go back to the facts, because the dramatized version, I’ve done; it’s Cold Water, it’s Disorder, it pops up here and there in my movies. Here, I didn’t want to distort the feeling, the emotions and the mood with the artifices of narration. That’s one side of it, the other side is it’s not me on the screen. It starts as autobiography and becomes fiction and yes, it becomes about re-creating my own weird path to cinema, but it also becomes about [actors] Clément Métayer and Lola Créton. Ultimately, they are the ones who embody the narrative.

OA: It has to do with the connection with writing. I am a writer and filmmaker and if it amounts an autobiography like this film or Cold Water, I think it’s the same process as making fiction; you draw on your own experience, you show your relation to the world, it’s always something when you write. But I guess this film even more so, as this is as autobiographical as it gets. I’m using factual elements, but because I have already used this material in a dramatized way, it was important to me to de-dramatize this version, to go back to the facts, because the dramatized version, I’ve done; it’s Cold Water, it’s Disorder, it pops up here and there in my movies. Here, I didn’t want to distort the feeling, the emotions and the mood with the artifices of narration. That’s one side of it, the other side is it’s not me on the screen. It starts as autobiography and becomes fiction and yes, it becomes about re-creating my own weird path to cinema, but it also becomes about [actors] Clément Métayer and Lola Créton. Ultimately, they are the ones who embody the narrative.

H2N: Would it be fair to say the sequel to Something In The Air is actually Carlos in some way?

OA: Yes, in some ways it is a companion piece to Carlos because that film is the ’70s seen from the point-of-view of the bigger picture. It is trying to expose what that bigger picture was about and to deal with those times through a character who was not just an everyday character but someone who was a myth, who embodied so many of the diverse energies of the time. After making Carlos, I needed to show my own naïve version of how I lived through the ’70s, and of course, I didn’t know the first thing about what was happening in the world that is shown in Carlos. That was completely out of my reach. In a way, you have the deconstruction of the times in Carlos and in Something In The Air, you have the actual thing, the mess it was, and the difficulty of understanding and deciphering it.

H2N: This film ends with this moment of discovery of personal purpose in cinema. The film is completely unsentimental and demythologized about this, though. I think a lot of counterculture “romantics” will be surprised at how the film refuses to wave a flag of celebration…

OA: Yeah, it would have been completely wrong. The ’70s are either ridiculed or romanticized and both are wrong. It’s easy to make fun of for its excesses, with, like, the Cheech & Chong stuff, you know? But at the same time, it’s wrong to romanticize it because the politics of the time were suffocating. They were so cut off from any reality; they believed so much in revolution that at some point they were living in a world that was not actually happening and they were reading “signs” in society or in the world that were a complete abstraction, like a religious abstraction. There was something disastrous going on and you could not be blind to that. To me, surviving the 1970s was thanks to the cinema, to the movies.

OA: Yeah, it would have been completely wrong. The ’70s are either ridiculed or romanticized and both are wrong. It’s easy to make fun of for its excesses, with, like, the Cheech & Chong stuff, you know? But at the same time, it’s wrong to romanticize it because the politics of the time were suffocating. They were so cut off from any reality; they believed so much in revolution that at some point they were living in a world that was not actually happening and they were reading “signs” in society or in the world that were a complete abstraction, like a religious abstraction. There was something disastrous going on and you could not be blind to that. To me, surviving the 1970s was thanks to the cinema, to the movies.

I had no notion of what the movies were about. Yes, I grew up in a family where my father wrote movies, but they were movies from another era. His friends were older guys. So, I knew I wanted to make movies, but I had no idea how movies were made and I didn’t want to make films the way my father’s friends made them; they belonged to another world. I was attracted to anything having to do with films that was obtainable in my world; some of it was international radical movies, anything was good enough. I would grab it just to make sense of it, but I didn’t know what my path was in cinema, how I could obtain a similar satisfaction that I had with painting and drawing.

I leave the character of Gilles at the end of the film when he finally understands what art is about and what cinema is. Maybe he will do something with it, maybe he won’t, but at least he understands that art is about resurrection, about bringing back to life what is lost, what has disappeared. It’s also the first time in the film when I show another movie in full frame; all of a sudden, he is in the film. He finally realizes that this is what he has been looking for. Before that, how could he relate to the politics of the Bolivian indios or mishmash of the Laotian uprising? That’s what movies were about. For me, I guess in terms of how things are constructed in the cinematic subtext of this film, I suppose that the films of Bo Widerberg gave a first hint of where to go. Widerberg is an amazing filmmaker whose films are all about the inscription of rebellion and revolution into pastoral landscapes, but there was something more central going on, which was possibly already a key; perhaps a tiny white stone on the path of Gilles.

H2N: In the book A Post-May Adolescence, the story builds and builds toward this revelation that the making of a film is, in practice, a working model for Situationism*. But we get to the end, and you write this very apologetic finale that maybe, just maybe and humbly, the film set can be, indeed, what Guy Debord was after. Can you preserve that feeling today? Is this really what you’re striving for when you make a film?

OA: Yes, yes. It’s something I’ve never lost view of. For me, there is before and after. Before, I had a precise idea what I was looking for. I wanted to tell my story, I was trying to be ambitious about it. I had a clear notion when I arrived on the set of precisely what I wanted to capture, usually close-ups. I didn’t care much about the set or the ambient stuff. Yes, it was about inventing things, but within a very defined framework. It was my narrative, including in the Bressonian sense. But at some point, I realized that there is something beautiful that a film set, somehow, puts into motion; it has to do with the light, the sunrise, the sunset, the beauty of the world around you. I’ve never again been blind to what is going on outside of my frame. At some point, I just dropped the notion of framing things. There is the story I’m trying to tell and there is the whole word around it. I want to capture both.

OA: Yes, yes. It’s something I’ve never lost view of. For me, there is before and after. Before, I had a precise idea what I was looking for. I wanted to tell my story, I was trying to be ambitious about it. I had a clear notion when I arrived on the set of precisely what I wanted to capture, usually close-ups. I didn’t care much about the set or the ambient stuff. Yes, it was about inventing things, but within a very defined framework. It was my narrative, including in the Bressonian sense. But at some point, I realized that there is something beautiful that a film set, somehow, puts into motion; it has to do with the light, the sunrise, the sunset, the beauty of the world around you. I’ve never again been blind to what is going on outside of my frame. At some point, I just dropped the notion of framing things. There is the story I’m trying to tell and there is the whole word around it. I want to capture both.

H2N: Was there an epiphany? Do you remember the moment?

OA: It’s really when I was shooting Cold Water and I had re-created the past, the situation with those kids who were like we were, more or less, who were having fun; they were not acting. The strongest moment when I realized it was the big fire in Cold Water. I realized it was stronger than cinema in the sense that, why were the kids so natural? Why was there this extraordinary energy beyond anything I had anticipated? The fire was so powerful, that is what attracted the kids. They were having fun, they could forget they were in a film. They were just living. It changed my perspective forever.

— Tom Hall

*For the uninitiated, from Wikipedia: “The situationists believed that the shift from individual expression through directly lived experiences, or the first-hand fulfillment of authentic desires, to individual expression by proxy (aka “the spectacle”), expression through the exchange or consumption of commodities, or passive second-hand alienation, inflicted significant and far-reaching damage to the quality of human life for both individuals and society. In situationist theory, the primary means of counteracting the spectacle was the construction of situations, moments of life deliberately constructed for the purpose of reawakening and pursuing authentic desires, experiencing the feeling of life and adventure, and the liberation of everyday life…Situationist publications proved greatly influential in shaping the ideas behind the May 1968 insurrections in France; quotes, phrases, and slogans from situationist texts and publications were ubiquitous on posters and graffiti throughout France during the uprisings.”

Pingback: HOME VIDEO PICKS – Hammer to Nail