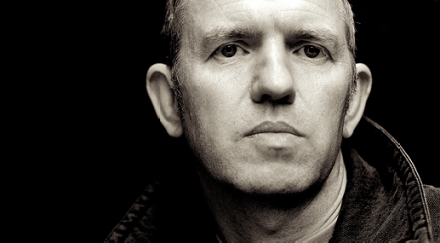

A Conversation with Anton Corbijn (LIFE)

Born in Strijen, Netherlands, in 1955, Anton Corbijn made his name in the 1970s as a photographer for cult British music weekly New Musical Express, creating iconic portraits of musicians ranging from David Bowie to Miles Davis, Captain Beefheart, Morrissey, Nick Cave, The Rolling Stones, Annie Lennox and The Cramps. He later became a prolific and highly acclaimed music video director, forming particularly close artistic relationships with the bands U2 and Depeche Mode.

Born in Strijen, Netherlands, in 1955, Anton Corbijn made his name in the 1970s as a photographer for cult British music weekly New Musical Express, creating iconic portraits of musicians ranging from David Bowie to Miles Davis, Captain Beefheart, Morrissey, Nick Cave, The Rolling Stones, Annie Lennox and The Cramps. He later became a prolific and highly acclaimed music video director, forming particularly close artistic relationships with the bands U2 and Depeche Mode.

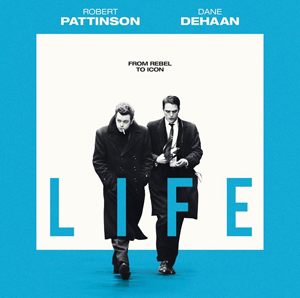

Corbijn came to feature films relatively late and somewhat reluctantly, opting to direct 2009’s Control, his austere and poignant biopic of late Joy Division vocalist Ian Curtis, because of his personal connection to Curtis rather than any desire to become a filmmaker. He followed up Control with the 2010 George Clooney vehicle The American and 2014’s A Most Wanted Man, an adaptation of the John LeCarré novel. His latest film was 2015’s Life, and exploration of the relationship between Life magazine photographer Dennis Stock and the young, pre-fame James Dean. He spoke to H2N at the Marrakech International Film Festival where he served on the jury under president Francis Ford Coppola.

Hammer to Nail: Did you have any experiences as a photographer that mirrored Dennis Stock’s with Dean?

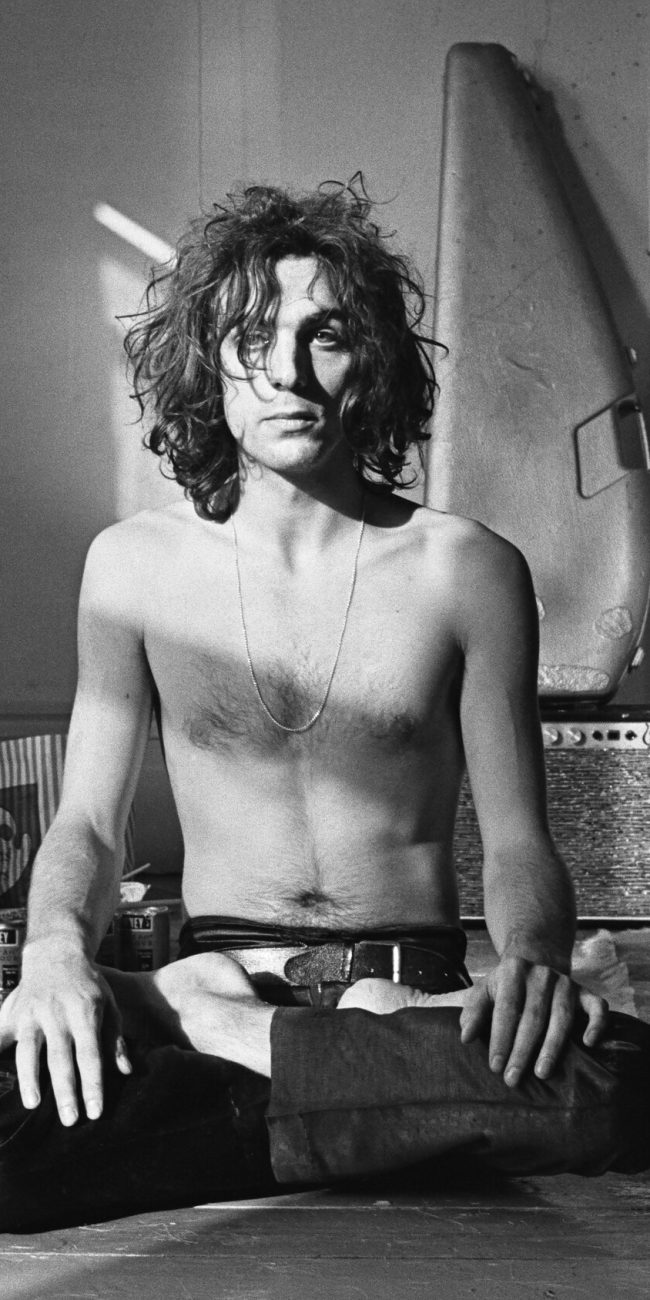

Anton Corbijn: Yes, with a Dutch pianist called Herman Brood. I took pictures of him, he liked them, I took more pictures and then he became a singer and we traveled a lot together. He was an incredible charmer, a painter and unfortunately also a junkie. But in Holland in the seventies it was more acceptable to be like that. Eventually he became the biggest rock star we’ve ever had in Holland, his career skyrocketed and then everyone wanted to photograph him. I didn’t understand the relationship between the photographer and the subject, I was thinking, What about me!? (laughs). That comes into the film. Robert Pattinson’s character calls Dean and says he wants to photograph him. Dean says, ‘Okay, I’d like to help you.’ And Stock says, ‘No, no, no. I’m helping you.’ He thought he was more important that the person he was photographing.

How did you come to make Control? Was it something you’d wanted to do for a long time?

AC: I have to say, everything I’ve ever done my whole life has been kind of accidental, even film making to a degree. I started making music videos because everyone said I should. They said, ‘You do everything else for us, you should make videos.’ So I reluctantly started doing that and when I became successful with that in the eighties, everyone said, ‘You should be making movies.’ I’m quite an introvert and thought I could never make a movie so I always said no. People would send me scripts and I could always think of a thousand people who could make a better film then I could so I always said no – until somebody said, ‘There’s [the] Joy Division story.’ Well, actually an Ian Curtis story. There is so much emotion with that story because I came to England when I was twenty-four to work with Joy Division, so I could so I could imagine I had an advantage over proper directors. That’s how I made my first film. I never thought I’d make another one so I put all my money into it. I lost most of it, and that’s why I had to move back to Holland. I came to England for Joy Division, then thirty years later I made a movie about them and had to go back (laughs). But I’m just starting on my fifth film, so I’m not complaining.

What can you tell us about your new project?

AC: It’s a film called Devil In The Grove, based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Gilbert King. Essentially, it’s about race relations in the late forties in Florida. It’s centered on a court case in 1949 where four black kids were accused of raping a white girl. The lawyer for the case was Thurgood Marshall who, many years later, became the first African American nominated to the Supreme Court.

What was it about that story that persuaded you to make a film of it?

AC: Of all the things I’ve read over the last year or more, it felt more relevant to what’s happening in America and what’s happening now in Europe. We all thought racial issues had gone away, but they so obviously have not. That was important to me, just like A Most Wanted Man was important to me post 9-11; it’s something that affected us all.

What stage of production are you at right now?

AC: The script has gone out to casting.

Do you have anyone in mind, your dream cast?

AC: Absolutely! (laughs). But I can’t share I’m afraid.

What parallels, if any, do you see between Ian Curtis and James Dean?

AC: Only that they both died young and left a legacy behind them. They were very different characters so I don’t see any similarities in that way. One died by his own hand and the other in an accident, so their states of mind were very different.

Do you feel a pressure of responsibility in depicting real life figures?

AC: It is difficult. With Ian it was slightly easier for me because I knew him, and it didn’t happen as long ago as James Dean. [Control] was based partly on the book by his widow Deborah (“Touching From A Distance: Ian Curtis And Joy Division”), but she didn’t like the girlfriend (Belgian music journalist Annik Honoré). So I couldn’t make the film based purely on the book, I had to incorporate the girlfriend. That was difficult and I don’t think his widow likes the film now. But for me it was honest to do it that way, so I didn’t take many liberties at all there. I took more liberties with James Dean, especially with the photographer. With Dean there’s not much you can get away with because so much was documented, but not a lot of people know Dennis Stock. We based the film around some of the pictures that he took, so there’s a structure to it and we imagined how the situations played out. We end the film where James Dean flies off to LA, as if they’re never going to see each other again. In fact they did see each other again; Dean hired him on his next film.

There have been some comments about your reluctance to portray Dean’s bisexuality. What’s your take on that?

AC: It’s not a biopic. It’s about Dennis Stock’s two weeks with James Dean and that element, which may or may not have been part of his character, was not an issue in their relationship. I think he probably was bisexual but that was not part of our story.

You’ve said your interest in the story was more to do with Dennis Stock than James Dean —

AC: More in the relationship between the photographer and the subject matter.

Was Stock an influence on you as a photographer?

AC: No. I knew some of his pictures but I never put two and two together until I read the script. I like a lot of his photographs, but he was much more of a documentary photographer than I am or ever was. He photographed people in their environment, which is what made his pictures of Dean so great. With portrait photographers you look back on their work sixty years alter and you don’t learn so much about the era. With documentary photographers you see so much more.

Like you, Stock also photographed a lot of musicians —

AC: Yes, mainly jazz musicians like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. But he photographed musicians in action, playing live in clubs. I’m much more of a portrait photographer.

You said you became a filmmaker reluctantly and that you never thought you’d make another film after Control. You’re now on your fifth feature, so there was obviously something about it that you enjoyed and that fulfilled you beyond telling one particular story.

AC: Yeah, I have to say, I had no agent when I made Control. I lost my house because of it; a lot of people made money but I didn’t. So how I got to make that film was outside of the film industry. It was my incredible emotional attachment to the story that made me do it. But then it won so many awards and so many people seemed to want to work with me, that I felt maybe I should explore whether I actually can make another film. So I went in completely the other direction and made a Hollywood film, in color, in a very different genre and with an American actor instead of English actors. I wanted a totally different experience.

It wasn’t just an American actor, it was one of the biggest movie stars in the world.

AC: Exactly, completely the opposite direction. Because after Control I got offered biopics of every diseased musician in the world. I thought, I’m not going to go that way. It was a very conscious decision to try something else. And it was a wonderful adventure. I was fifty-one when I made Control, which is late in life to try something completely new.

Even though it is a Hollywood film, The American is hardly a typical ‘Hollywood’ thriller. Not many studio films boast influences ranging from Spaghetti westerns to Nicholas Roeg and Graham Greene.

AC: No, it was a very European film in many ways. But I went through the system, an American studio, to make it. So the experience of how you make films was important for me.

Can you talk about those different influences?

AC: I never thought I was going to be a filmmaker. After Control I had no idea what I wanted to do, but I knew I wanted to tell stories in that way. At first I was looking for a Western but I couldn’t find one. Then I read “A Very Private Gentleman” (source novel for The American) and I thought, I can make into kind of a Western – there’s a shoot-out, the guy leaves town, he hides out, he befriends a priest and a prostitute, his past catches up with him then there’s another shoot-out and he leaves town again. So that’s how I structured the film. I actually talked to Ennio Morricone about doing the music for it, but it was going to be old music so I didn’t follow that up. But the Spaghetti Western influence was always there – the title I wanted to use was Il Americano, but the studio wouldn’t let me. It’s ‘The American’ pronounced incorrectly in Italian because it’s about somebody who tries to fit in but doesn’t quite.

What about Nic Roeg?

AC: I don’t know. Who said that?

You did. You said when you were shooting in the small town you wanted it to have the same feel as Venice in Roeg’s Don’t Look Now.

AC: Did I really say that? Well, I love that film so I could have (laughs). Nic Roeg was an interesting filmmaker, especially for me because he was one of few directors who used musicians well as actors, be it Art Garfunkel or Bowie or Jagger. I don’t recall saying he was an influence, but you might be right.

You’re on the jury here at the Marrakech festival. How do you tend to judge movies, with the eyes of a photographer or with the eyes of a filmmaker?

AC: When I look at films, I look for a good story and whether that story is well told. Cinematography is all part of how you tell a story, but I try to look at films as a director. Cinematography can be easy; it’s very easy to make something look good, and people think that’s great filmmaking. In a way it’s a safety net. My first two films I concentrated very hard on the composition of every shot. My last film I did hand-held because I didn’t want to have that safety net.

Just to complete the set, what was it about A Most Wanted Man that appealed to you?

AC: It was a John LeCarré novel, maybe not his best one, but the story was interesting to me because it dealt with the post-911 era and how the effects of 911 has crept into our lives, how we judge people very quickly, how things are seen in black and white and how it polarizes societies. Of course, when we made the film society was already much more polarized than when he wrote the book, and he wrote the book years after the event. Now the world is so polarized that anything you can do to help look at that issue, or to promote discussion of it, is helpful.

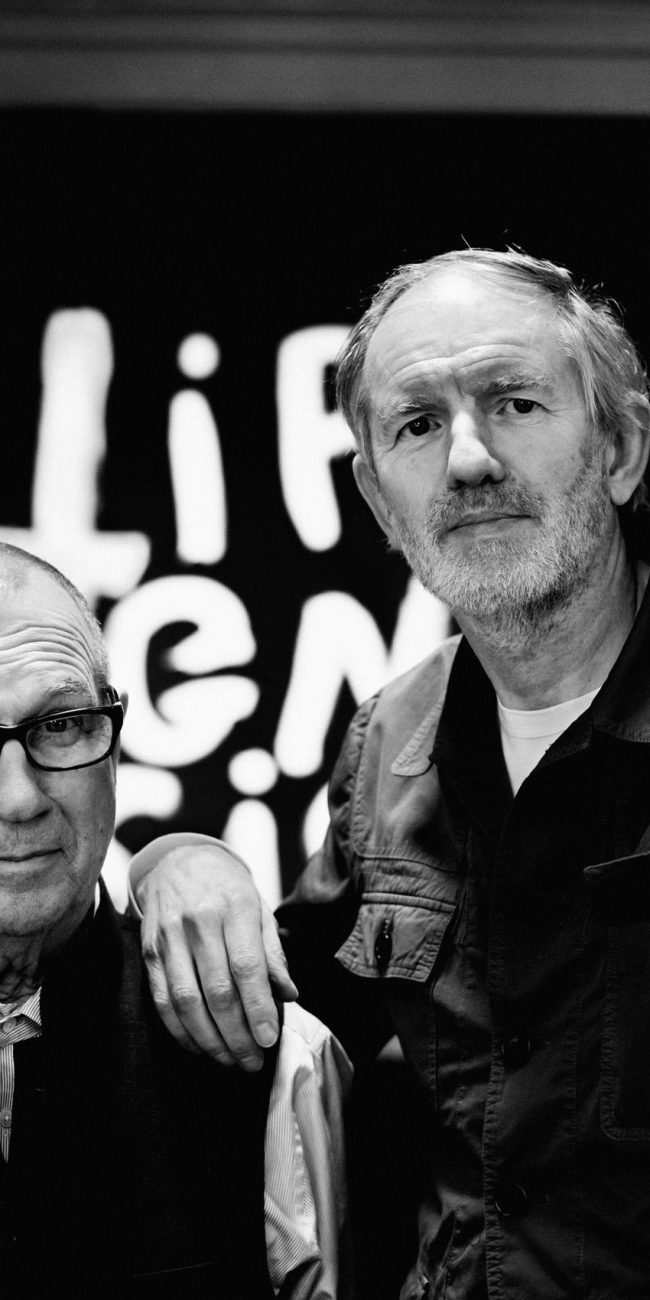

Did you have much contact with LeCarré while you were making the film?

AC: He came to the set twice, which was very helpful and I met him a few times prior to making the film. A fascinating man, very mysterious and you can’t trust the things he says because he invents stories.

Your next film has a political dimension. Do you find the stories you’re drawn to tend to be political in nature?

AC: My next film definitely is, but the one after probably won’t be. I don’t want to become just a messenger. There are many interesting stories to be told. Personally, I like dark comedies very much so I’d like to make one of those.

Do you have any favorites?

AC: I like the Cohen Brothers.

Any in particular?

AC: Fargo. Or The Big Lebowski.

– Simon Braund