SXSW ’14: MIKE S. RYAN’S WRAP-UP

On a panel called “Is This The 21st Century Media Conglomerate?”, the golden era dynamic duo (I mean golden literally, as in gold/money) of John Pierson and John Sloss tossed around various views of the current state of indie compared to the past. Pierson bemoaned the lack of distributor transparency and Sloss stated that there is more private equity investing in film than ever before. Pierson begrudgingly used the term “monetize” while Sloss worked hard to appear positive. But there is reason to be positive, at least for the content creators: it is easier and cheaper than ever to make your film, and get it placed on a digital platform for mass viewing. Drawing a large audience is the main problem, but perhaps the current focus on curation, via subscription viewing platforms, will soon help on that front. In the meantime, the content exploiters—namely, the distributors—are scared shitless. They are feeling the pinch and that fear is reflected in their very conservative buying trends. I’m not just talking about the lower MGs; I’m talking about their belief that the feature film consumer wants films that are softer than a episode of The Office or Parks and Recreation.

On a panel called “Is This The 21st Century Media Conglomerate?”, the golden era dynamic duo (I mean golden literally, as in gold/money) of John Pierson and John Sloss tossed around various views of the current state of indie compared to the past. Pierson bemoaned the lack of distributor transparency and Sloss stated that there is more private equity investing in film than ever before. Pierson begrudgingly used the term “monetize” while Sloss worked hard to appear positive. But there is reason to be positive, at least for the content creators: it is easier and cheaper than ever to make your film, and get it placed on a digital platform for mass viewing. Drawing a large audience is the main problem, but perhaps the current focus on curation, via subscription viewing platforms, will soon help on that front. In the meantime, the content exploiters—namely, the distributors—are scared shitless. They are feeling the pinch and that fear is reflected in their very conservative buying trends. I’m not just talking about the lower MGs; I’m talking about their belief that the feature film consumer wants films that are softer than a episode of The Office or Parks and Recreation.

I knew it was starting to get bleak when the pseudo-critics and kiddie bloggers at Sundance started falling in lockstep with the market driven opinions of the distributors looking for get-rich-quick product. I actually started hearing “critics” in line at Sundance saying stuff like, “Yeah, it’s a good film but it’s so dark no one will go for it,” or, “It’s cool but I have no idea who the audience is for that.” I’m sorry, but saying that a film may not have an audience is not a valid criticism. We are not in the business of making widgets or potato chips. But as if it weren’t bad enough that young critics are picking up on the distributors’ bad faith complaints, now there are young filmmakers who are also jumping on that bandwagon and making films that they think will satisfy both those whiny pop critics and the distribs. Sorry guys, it doesn’t work like that.

Right now, the distribs are wrong in thinking banal, light, impersonal indie films will sell and connect to an audience. Most of Sundance’s 2012 crop of purchased fluff failed at the box office in 2013, and yet look at the serious dramas that were at this year’s Oscars. Why are most indie films less edgy than Oscar nominated films? Does something not smell right in the indie world when the Oscar nominees have more edge and vision than most Sundance titles?

Yes, indie is in a serious crisis right now. I don’t have the answers about how to win back the trust of the filmgoers who were betrayed by year after year of Juno-inspired mush, but I can tell you one thing: we ain’t gonna move forward by making Three’s Company/King of Queens feature format TV sitcom rehashes. Consumers have better platforms and cheaper formats to get their distracting simple entertainment fix, it sure as heck ain’t the feature film format. Those young filmmakers are who are jumping on the make-an-easy-lite-feature-as-a-‘calling card for a TV sitcom pilot’-trend will disappear into the ether, as will their films. What will stand are the personal visions that boldly express a point-of-view that is extreme, outlandish, dark, and/or completely original. That is why SXSW 2014 made me feel good about the future of the American Indie. There are still plenty of great films that are fighting the sitcom TV trend. Many of these new filmmakers, the class of 2014, may indeed grow to become the next SXSW auteur alumni (like the Zellner Brothers, whose fantastic Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter played in the Festival Favorites section). Here are some of the highlights that marked the arrival of strong new voices that have the courage to challenge themselves and their audiences.

Buzzard (Joel Potrykus, 97m) — Buzzard is the ultimate misanthropic madman anti-hero one-man-show indie film. Strongly following the best of the genre such as Damon Packard’s Reflections of Evil, Ronald Bronstein’s Frownland, Rick Alverson’s The Comedy, and Todd Solondz’s Fear, Anxiety and Depression, Buzzard follows the steep decline of desperate anti-everything Freddy Krueger loving punk hero Derek (played by Joshua Burge) as he torments co-workers at a bank and then is forced out onto the streets to fend for himself. Like the best films of this genre, Buzzard challenges us by the mere act of daring us to sympathize with an outsider who is loathsome, pathetic, and sad, and simultaneously driven to excess by a society that could care less about his dissatisfaction and disappointment.

Buzzard (Joel Potrykus, 97m) — Buzzard is the ultimate misanthropic madman anti-hero one-man-show indie film. Strongly following the best of the genre such as Damon Packard’s Reflections of Evil, Ronald Bronstein’s Frownland, Rick Alverson’s The Comedy, and Todd Solondz’s Fear, Anxiety and Depression, Buzzard follows the steep decline of desperate anti-everything Freddy Krueger loving punk hero Derek (played by Joshua Burge) as he torments co-workers at a bank and then is forced out onto the streets to fend for himself. Like the best films of this genre, Buzzard challenges us by the mere act of daring us to sympathize with an outsider who is loathsome, pathetic, and sad, and simultaneously driven to excess by a society that could care less about his dissatisfaction and disappointment.

The Mend (John Magary, 111m) — The Mend was probably my favorite first feature that I saw this year. It was utterly challenging in a way that left you destabilized as you actively looked for a center or point of focus. The score was used as a means to challenge your attitude toward the scene and characters and the overall effect was frustrating at times, yet the palpable passion of the main character Mat (Josh Lucas), kept it all tottering forward like a drunken master. Comparable to Cassavates on cocaine, The Mend is an example of a filmmaker willing to adhere to a narrative point-of-view that challenges his own characters’ assumptions about their reality, resulting in one of my more memorable screening experiences.

The Mend (John Magary, 111m) — The Mend was probably my favorite first feature that I saw this year. It was utterly challenging in a way that left you destabilized as you actively looked for a center or point of focus. The score was used as a means to challenge your attitude toward the scene and characters and the overall effect was frustrating at times, yet the palpable passion of the main character Mat (Josh Lucas), kept it all tottering forward like a drunken master. Comparable to Cassavates on cocaine, The Mend is an example of a filmmaker willing to adhere to a narrative point-of-view that challenges his own characters’ assumptions about their reality, resulting in one of my more memorable screening experiences.

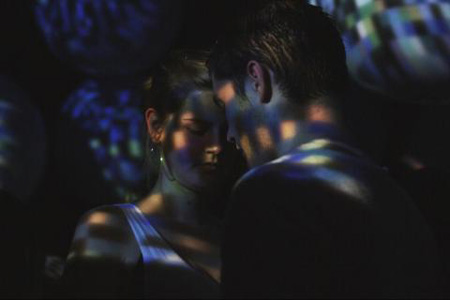

The Heart Machine (Zachary Wigon, 85m) — This was just one of the films that touched on the intimacy-versus-technology theme prevalent throughout all of the festival’s sections this year. Though it is less articulate and focused than the similarly themed Her, The Heart Machine is way more interesting on a structural and visual level in part due to the bifurcation of the narrative between both the man (John Gallagher Jr.) and the pursued woman (Kate Lyn Sheil), who in the end becomes the hunter. It’s another iconic performance from Sheil, who is singlehandedly collecting a pile of various Brooklyn hipster female roles. Although at times I wanted the film to become more like a Brooklyn hipster Looking For Mr. Goodbar, the film provides a dark side slice of hipster disconnection and exhibits an awareness from the director that there is a problem with his generation’s attitude toward dating and relationships.

The Heart Machine (Zachary Wigon, 85m) — This was just one of the films that touched on the intimacy-versus-technology theme prevalent throughout all of the festival’s sections this year. Though it is less articulate and focused than the similarly themed Her, The Heart Machine is way more interesting on a structural and visual level in part due to the bifurcation of the narrative between both the man (John Gallagher Jr.) and the pursued woman (Kate Lyn Sheil), who in the end becomes the hunter. It’s another iconic performance from Sheil, who is singlehandedly collecting a pile of various Brooklyn hipster female roles. Although at times I wanted the film to become more like a Brooklyn hipster Looking For Mr. Goodbar, the film provides a dark side slice of hipster disconnection and exhibits an awareness from the director that there is a problem with his generation’s attitude toward dating and relationships.

Other Months (Nick Singer, 69m) — A three-part journey into a moody post college grad’s head space. Each part represents a different tone and employs a different visual style. Although at times it’s dragged down by a compulsive verbosity, this is an excellent first film in which both character and plot are explored through evocative compositions, lighting, and editing. This is what I mean about filmmakers having the courage to venture forth into unknown narrative waters without clinging to the life preservers of contrived plot twists and quirky dialogue. Other Months is the type of film that makes SXSW special in that such an exploratory film without stars is programmed in a very selective category. If only there were more such courageous young filmmakers as well as more festival programmers who were as equally bold. I can’t wait to see Singer’s next film.

Other Months (Nick Singer, 69m) — A three-part journey into a moody post college grad’s head space. Each part represents a different tone and employs a different visual style. Although at times it’s dragged down by a compulsive verbosity, this is an excellent first film in which both character and plot are explored through evocative compositions, lighting, and editing. This is what I mean about filmmakers having the courage to venture forth into unknown narrative waters without clinging to the life preservers of contrived plot twists and quirky dialogue. Other Months is the type of film that makes SXSW special in that such an exploratory film without stars is programmed in a very selective category. If only there were more such courageous young filmmakers as well as more festival programmers who were as equally bold. I can’t wait to see Singer’s next film.

Late Phases (Adrian Garcia Bogliano, 95m) — One of the best films I saw in a once again very strong Midnight section was this straightforward-but-brilliant werewolf movie. As with Xan Cassavettes’ Kiss Of The Damned from last year, I am most attracted to genre purists who work within the three-chord structure of their respective genre and through rigorous personal exploration of the core foundations of the code, completely reinvent the genre. Late Phases starts deceptively simple, with a very tart TV-movie-of-the-week set-up and pacing but, by the middle of the second act, gets torn to bits like the graphic transformation scene in which we watch a trusted deacon in the church pull off his nose and ears as hair pokes through his chest cavity. Or the bizarre scene on a church bench when the head priest (Tom Noonan) and our war hero Ambrose (Nick Damichi) talk about the evil that men do while describing the act of killing innocent children. The transformation from human to monster is ripe for so much fertile metaphorical relationships; the most obvious one here is the transformation from youth to old age heightened by the fact that the film is set in an old age retirement community. I also particularly liked the father/son relationship, which opened up the idea that as sons, we all become our fathers, as much as we fight the urge; at times, we all feel that matted, nasty smelling hair poking out, or at least clawing to get out. Likewise, we are willing to shoot ourselves in the foot in order to kill that evil beast. Hats off to low-budget horror masterminds Larry Fessenden and Brent Kunkle at Glass Eye Pix, who manage to make creatures and effects feel more real than any mega-budget CGI extravaganza on I am sure what is a nano-percentage of the typical Hollywood budget. This is one film that I hope gets into every megaplex. It’s elevated the werewolf film to a whole other level.

Late Phases (Adrian Garcia Bogliano, 95m) — One of the best films I saw in a once again very strong Midnight section was this straightforward-but-brilliant werewolf movie. As with Xan Cassavettes’ Kiss Of The Damned from last year, I am most attracted to genre purists who work within the three-chord structure of their respective genre and through rigorous personal exploration of the core foundations of the code, completely reinvent the genre. Late Phases starts deceptively simple, with a very tart TV-movie-of-the-week set-up and pacing but, by the middle of the second act, gets torn to bits like the graphic transformation scene in which we watch a trusted deacon in the church pull off his nose and ears as hair pokes through his chest cavity. Or the bizarre scene on a church bench when the head priest (Tom Noonan) and our war hero Ambrose (Nick Damichi) talk about the evil that men do while describing the act of killing innocent children. The transformation from human to monster is ripe for so much fertile metaphorical relationships; the most obvious one here is the transformation from youth to old age heightened by the fact that the film is set in an old age retirement community. I also particularly liked the father/son relationship, which opened up the idea that as sons, we all become our fathers, as much as we fight the urge; at times, we all feel that matted, nasty smelling hair poking out, or at least clawing to get out. Likewise, we are willing to shoot ourselves in the foot in order to kill that evil beast. Hats off to low-budget horror masterminds Larry Fessenden and Brent Kunkle at Glass Eye Pix, who manage to make creatures and effects feel more real than any mega-budget CGI extravaganza on I am sure what is a nano-percentage of the typical Hollywood budget. This is one film that I hope gets into every megaplex. It’s elevated the werewolf film to a whole other level.

Evaporating Borders (Iva Radivojevic, 73m) — This was one of the Visions section docs that stood outside of the standard issue reportage format. Though very much driven by the topic of third world immigration into the EU through Cyprus, the film presents that topic through the first-person lens of the self-critical narrator/director. Here, compositions and angles shot from an oblique angle work to achieve a critical distance that eventually boomerangs around to target the actual narrator. In a dark alley, our narrator encounters some shady characters, recounted as a travelogue tale; the narrator soon turns the tables on herself and wonders why she assumed the swarthy characters standing in the shadows were suspicious or worthy of her fear. Evaporating Borders manages to ask questions about the origins of our identity as well as our need to create a national identity and how that identity relates to the creation of an enemy. A diary/essay film that starts out as description of a place—Cyprus—and a situation—migration patterns into the EU—soon morphs into an meditation on the nature of identity, creation, and maintenance. A very interesting and personal film.

Evaporating Borders (Iva Radivojevic, 73m) — This was one of the Visions section docs that stood outside of the standard issue reportage format. Though very much driven by the topic of third world immigration into the EU through Cyprus, the film presents that topic through the first-person lens of the self-critical narrator/director. Here, compositions and angles shot from an oblique angle work to achieve a critical distance that eventually boomerangs around to target the actual narrator. In a dark alley, our narrator encounters some shady characters, recounted as a travelogue tale; the narrator soon turns the tables on herself and wonders why she assumed the swarthy characters standing in the shadows were suspicious or worthy of her fear. Evaporating Borders manages to ask questions about the origins of our identity as well as our need to create a national identity and how that identity relates to the creation of an enemy. A diary/essay film that starts out as description of a place—Cyprus—and a situation—migration patterns into the EU—soon morphs into an meditation on the nature of identity, creation, and maintenance. A very interesting and personal film.

The 78 Project Movie (Alex Steyermark, 95m) — The Presto direct-to-disc recorder cuts a 78rpm record as the sound is recorded. Used primarily by field ethnologists like Alan Lomax, starting in the 1930s, the machine captures voice and instrument with a singular primacy that conveys the aura of space and tone in a way that digital formats are unable to process. In this film, Steyermark and writer/co-producer Lavinia Jones Wright travel the country to record classic songs performed by talented musicians who are then filmed listening back to the recording. The 78 Project Movie documents the magic that still can occur through the vibration of vocal cords captured by the vibration of a needle scratching a lacquer platter, which is then transformed into a playback recording.

The 78 Project Movie (Alex Steyermark, 95m) — The Presto direct-to-disc recorder cuts a 78rpm record as the sound is recorded. Used primarily by field ethnologists like Alan Lomax, starting in the 1930s, the machine captures voice and instrument with a singular primacy that conveys the aura of space and tone in a way that digital formats are unable to process. In this film, Steyermark and writer/co-producer Lavinia Jones Wright travel the country to record classic songs performed by talented musicians who are then filmed listening back to the recording. The 78 Project Movie documents the magic that still can occur through the vibration of vocal cords captured by the vibration of a needle scratching a lacquer platter, which is then transformed into a playback recording.

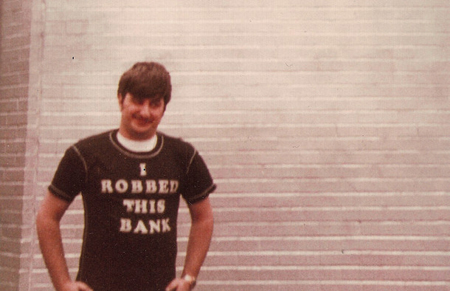

The Dog (Allison Berg and Frank Keraudren, 101m) — One of the most powerful aspects of cinema is that we can actually see people age a lifetime over the course of two or three hours. We saw it in the sweet episodic feature Boyhood by Richard Linklater, and here we see it in this documentary that follows the actual bank robber whose story was partially told in Dog Day Afternoon. All most of us know is that a crazy Brooklyn man tried to rob a bank in order to raise money for his lover’s sex change operation. But that is only a fraction of the intense story that was the life of John Wojtowicz. Spanning over 10 years of documenting a strange relationship between filmmakers and subject, the film is a journey into a life lived fully. Moving deftly and effortlessly between multiple time periods within John’s life, the film is a tour-de-force of visual narration that weaves a story that continually engages without a reliance on sleazy plot twist devices so popular with today’s documentarians. The Dog is both a poetic rumination on the essence of life and love as well as a time machine snapshot of a very particular type of NYC gay life that spans the periods pre-Stonewall era through the ‘80s into the present day. It is one of the best documentaries I have seen in years.

The Dog (Allison Berg and Frank Keraudren, 101m) — One of the most powerful aspects of cinema is that we can actually see people age a lifetime over the course of two or three hours. We saw it in the sweet episodic feature Boyhood by Richard Linklater, and here we see it in this documentary that follows the actual bank robber whose story was partially told in Dog Day Afternoon. All most of us know is that a crazy Brooklyn man tried to rob a bank in order to raise money for his lover’s sex change operation. But that is only a fraction of the intense story that was the life of John Wojtowicz. Spanning over 10 years of documenting a strange relationship between filmmakers and subject, the film is a journey into a life lived fully. Moving deftly and effortlessly between multiple time periods within John’s life, the film is a tour-de-force of visual narration that weaves a story that continually engages without a reliance on sleazy plot twist devices so popular with today’s documentarians. The Dog is both a poetic rumination on the essence of life and love as well as a time machine snapshot of a very particular type of NYC gay life that spans the periods pre-Stonewall era through the ‘80s into the present day. It is one of the best documentaries I have seen in years.

**SPECIAL MENTION** needs to go to composer Michael Montes, whose score contributions to two projects were so rigorous, inventive, dynamic and fun, they became key components of both films. Both Wild Canaries and Ping Pong Summer were shot full of Montes adrenaline. This is what comedy scores should be like: transgressive, bodacious, tart and unpredictable. I can’t wait to buy both of these soundtracks on CD!

As for what the jury was thinking regarding the narrative feature competition, I, and most everyone else, has absolutely no idea what their criteria was. But I only saw a small fraction of the total festival selection and though I know there was lots of lite, escapist “Oops I Farted” TV sitcom mush, there was more than plenty of genuinely personal indie cinema. It was a very good SXSW this year, despite this being a pathetic year for indie overall. Compared to the Oscars, popular American Indie has been shown to not be the place where one goes for honest challenging drama. Many of the films at this year’s SXSW challenged that shameful trend.

— Mike S. Ryan