Paul Schrader’s lonely man trilogy—American Gigolo, Light Sleeper, and The Walker—are pretty much the same movie told in different settings with slightly dissimilar characters. These pictures all have a hero that is hung out to dry by his “friends” after a murder. Two of them end with the same exact scene—the protagonist in jail talking to the one person who actually does care about him. And the three films can all be seen, to varying degrees, as metaphors for being an artist in the movie biz.

Mamet is obsessed with the movie biz too. How it fucks with the artiste, treats the artiste like shit. But he usually just tackles it head on. Chiwetel Ejiofor, in the great Redbelt, slowly realizes that the movies are no place for a martial artist. The straight up anti-Hollywood film has always been with us. From Nicholas Ray’s In A Lonely Place to Robert Altman’s The Player. But for some reason Schrader’s lonely man movies, by not ever outright being about Hollywood, seem the most vicious and suspicious. It’s the writer/director/actor painted as whore, drug dealer, or society walker. The trilogy is as nasty as Sweet Smell Of Success, but maybe even more macabre.

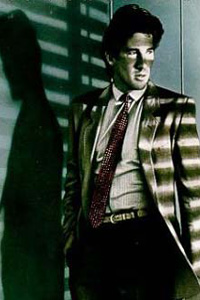

The worlds of these three films are swank with Armani jackets and cashmere scarves. There are sports cars and limos, smooth flesh and good drugs. But from the get-go, we’re uncomfortable. And the more glamour Schrader trots out in front of us, the more it becomes obvious that we’re watching a nightmare unfold. Here, Schrader seems to say. You want this? Do you really want this? Cross your heart and hope to die?

By now everyone knows all the insides and outs about the film industry thanks to shows like Entourage. But Schrader rips the cuteness away. Agents are straight-up pimps. Producers are murdering coke fiends. If we’re desperate enough to get in bed with them, we’re inviting hell into our life. Bleak stuff for sure. And Schrader’s movies do have enough flaws that there are times one may wonder if he’s just off his rocker, a raging bull, looking over his shoulder too much, Travis Bickle’d out, fried to a crisp by Catholic imagery and Scorsese prattle.

But damn if these films don’t stick in the brain and the chest. And as times goes on and I’ve been around movies a little, I see that he wasn’t kidding at all. Or even being overly dramatic. Over a dozen times I’ve gotten script notes back from agents simply saying “More Sex and Violence.” Nevermind that the movie is about a Zen monk. And the people you look out for, try to get work for—they disappear if you don’t have a movie in pre-production. Even the actor who you think is your best friend in the world—watch out. They get some attention, start googling themselves all the time, turn into a red carpet zombie.

But damn if these films don’t stick in the brain and the chest. And as times goes on and I’ve been around movies a little, I see that he wasn’t kidding at all. Or even being overly dramatic. Over a dozen times I’ve gotten script notes back from agents simply saying “More Sex and Violence.” Nevermind that the movie is about a Zen monk. And the people you look out for, try to get work for—they disappear if you don’t have a movie in pre-production. Even the actor who you think is your best friend in the world—watch out. They get some attention, start googling themselves all the time, turn into a red carpet zombie.

One interesting thing about Gigolo, Sleeper and Walker is that all three of the heroes realize there is no way, no chance of surviving in these worlds. They all come to the same conclusion: Escape. Get out. Because you can’t beat yourself. There are certain places and situations where one doesn’t stand a ghost of a chance. The way an NA member only walks down specific streets. The way an ex-con goes home early. The way veterans stay away from fireworks. Or they don’t.

Schrader’s trilogy is certainly rooted in noir (Pickup on South Street‘s Richard Widmark and Sam Fuller coulda stood in nicely for Willem Dafoe and Schrader many years ago). But these Schrader films are not ultimately noir. They all end with hope, a lost man found. There is however some wonderful playing around with noir stuff. In Light Sleeper, nice girl Dana Delaney turns out to be something closer to a femme fatale. Whereas Susan Sarandon, a drug dealer, breaks free of the game and shows a golden heart. The ultimate art, Schrader seems to be saying, is the art of seeing through a mirage. As Richard Gere’s Gigolo lays out his choice of outfits on the bed, he is listening and singing along to Smokey Robinson:

“Just like the desert shows a thirsty man

A green oasis where there’s only sand

You lured me into something I should have dodged

The love I saw in you was just a mirage”

The mirage looms large in America these days. Facebook fame, Twitter name, Xbox gunning bitter games. The reindeers have all gone home. Innocence is just a commodity to be spun into spider slut leggings. We seem to live more unchecked lives than ever. Cities full of creatures hiding from their own shadows and despair. Self reflection transformed into self projection—how many texts did you get today? Kierkegaard called this “inauthentic despair.” When someone doesn’t know himself, and doesn’t have the tools to take the backward step and look inside himself—that’s when everyone else’s opinion becomes the be all and end all. Richard Gere’s Julian spends most of his time working on his abs. Schrader examines this way of life, this country, again and again. The ugliness of our culture. The ugliness of himself and his desires. Blindness. And then, through a terrifying journey, the redemption of his central character. And maybe, the redemption of himself as an artist.

I guess salvation from one’s despair is not possible without feeling pain. There’s no trick or way around it. And so these three films are painful, fucked up voyages we’d sometimes like to turn away from. Woody Harrelson is absolutely heartbreaking in The Walker. But if we turn away, we go to sleep, get lost in entropy. Maybe we have to wound ourselves to get free from the comforting things that have been slowly killing us.

I guess salvation from one’s despair is not possible without feeling pain. There’s no trick or way around it. And so these three films are painful, fucked up voyages we’d sometimes like to turn away from. Woody Harrelson is absolutely heartbreaking in The Walker. But if we turn away, we go to sleep, get lost in entropy. Maybe we have to wound ourselves to get free from the comforting things that have been slowly killing us.

It is a sad and funny truth that Schrader is harping on, but it is definitely a truth. We don’t know who our real friends are until the shit hits the fan. Until it’s not easy to be friends with us. Then and only then do we get a real taste of the landscape. The characters played by Dafoe, Gere, and Harrelson all tell themselves that they are respected and valued. But they’re only respected and valued so long as they are charming and suave. Anything other than that is not acceptable. Especially any kind of trouble. Then they become lepers knocking on locked doors.

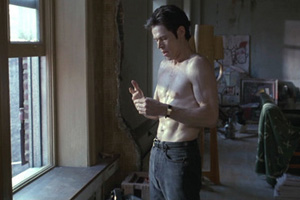

Dafoe’s drug dealer, John LeTour, keeps going to a fortune teller and asking her if his luck has run out. She tells him it hasn’t. But there’s a catch. She doesn’t say it, but it’s in her expression—a Ford Frick asterisk. He’s gotta shed a layer of skin, cast aside his old self, set the twilight reeling. His heart may still have some luck left, but not in the suit he’s wearing. He’s gone as far as he can in this role. Up late, he sits in his empty apartment, smokes, jots subconscious in a journal. “I can be good,” he writes, surprising himself in the middle of a ghostly night.

So get in and get out, right? Do what you gotta do and then go home. But we’ve all seen that movie too. The ‘I just gotta do this one last job’ movie. There’s no question it’s possible. Harry Houdini got out of all kinds of jams. But I bet he was always obsessing over magic. I bet he never got out of that. And Harry Lime didn’t get out at all.

So get in and get out, right? Do what you gotta do and then go home. But we’ve all seen that movie too. The ‘I just gotta do this one last job’ movie. There’s no question it’s possible. Harry Houdini got out of all kinds of jams. But I bet he was always obsessing over magic. I bet he never got out of that. And Harry Lime didn’t get out at all.

We don’t normally see movies from guys like Paul Schrader. I think most people who have touched lonesomeness and darkness to the extent Schrader has—most of them end up homeless, or dead from suicide, or shooting drugs in a freezing motel room, or in a mental ward. Just that he made these movies is deeply moving to me. Mishima, Hardcore, Affliction, and Blue Collar are like that too. They ring truer than a lot of virtuoso director films.

I’m at a party. It’s my birthday party. There’s a banner hanging from wall to wall, but it doesn’t say Happy Birthday. It says Film Is Forever. Which I know is total bullshit. Everything is impermanent except eternity, no matter what Tom Cruise says. I look out the window and see New York buildings. They’ll all be dust one day. New Order is playing “Bizarre Love Triangle”:

“I feel fine and I feel good

I feel like I never should

Whenever I get this way

I just don’t know what to say

Why can’t we be ourselves like we were yesterday?“

I look around. Various famous actors I’ve done films with are there. Casts and crews. But I look for my family, and they’re not there. And I look around for my old friends, and they’re not there. And I look for my girl, and she’s not there. Or she is, but she’s someone else kinda. And she comes up and kisses me on the cheek. Her lips are real cold. She whispers in my ear: “Make a wish.” Her voice chills my spine. I’m not sure what this could mean. I don’t think she’s what she seems. And then I’m running. I’m running down alleys. I’m running through parades. I’m running through cafes. And the party is chasing me. I know they mean to kill me. I know they do. But I’m running fast. I pass clowns and money. Rats and subway cars. Microphones and needles. Strip clubs. Magazines covered in bulimic vomit. I make it to my old neighborhood—where I grew up. And I know these streets. I know the nooks and crannies. I know the secret places, where traps and snares can’t reach me. For a moment I’m like the dragon returning to the water, like the tiger when it returns to the mountain. They won’t find me. But you. Maybe you remember. Though I don’t hardly deserve it, maybe you’ll meet me here.

— Noah Buschel

Gary Lundgren

Don’t believe it when they say to keep your friends close and your enemies closer.

Keep your true friends/family close and run from the BS. Even if it means not making movies